drawing, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 205 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

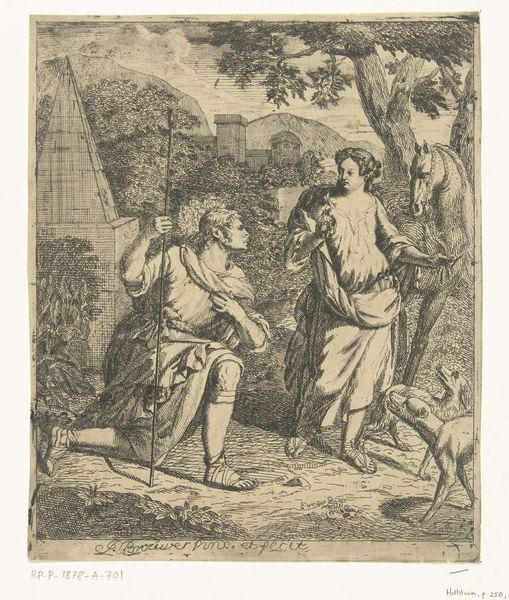

Editor: Here we have "Pastorale scène met Dameet, Galate en Amaril" by Gerard Hoet, made sometime between 1658 and 1733. It's a pen and ink drawing, and it feels quite theatrical, like a scene from a play. There's definitely a male gaze at work, particularly in how Galate is portrayed. What's your take on it? Curator: It is theatrical, isn't it? But let's dig into that male gaze you mentioned. How does the social context of the Dutch Golden Age influence how we see these figures? Consider the power dynamics inherent in representing female figures in art, especially in a 'pastoral' setting. Is this idyllic scene truly innocent, or does it participate in objectifying and idealizing women, thereby reinforcing certain social hierarchies? Editor: So, you’re saying it's not just a pretty picture but reflects societal power structures of the time? I hadn't thought about it that deeply. I guess the contrast between the clothed male figure and the nude figures becomes more charged then. Curator: Precisely. And the 'pastoral' genre itself is laden with artifice. These scenes are rarely about authentically representing rural life; more often they’re about constructing an idealized escape, a playground for the elite, where traditional power structures are naturalized and celebrated. How do the gazes of the figures play into this dynamic? Editor: It does make you wonder who the artwork was for, and whose perspective is prioritized. So, the ‘idyllic’ scene might be masking something darker? Curator: "Masking" is a strong word. More like refracting, or perhaps naturalizing. It allows viewers of the time—wealthy patrons, predominantly men—to indulge in these images without necessarily interrogating their own positions of privilege and authority. Now, does this awareness change how you perceive the drawing’s composition, technique, or even its inherent beauty? Editor: Absolutely, it reframes everything. I see the drawing now as less of a simple representation, and more as an artifact carrying a lot of cultural baggage. It gives me more to explore about the historical narrative and social dynamics in it. Curator: Exactly! And that’s the power of looking at art through a critical lens. It invites us to engage in dialogue with the past and understand its reverberations in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.