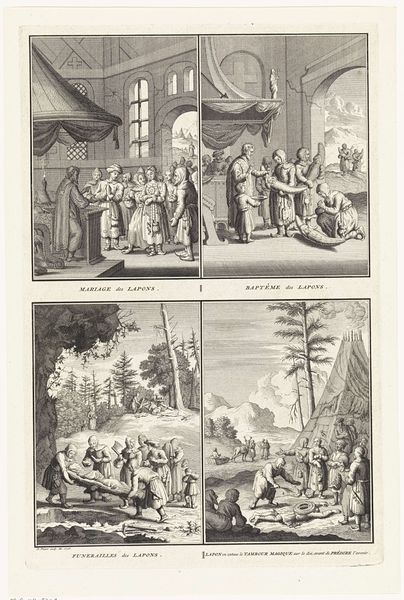

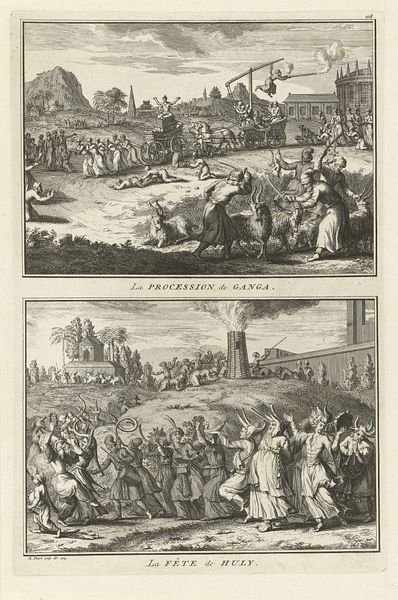

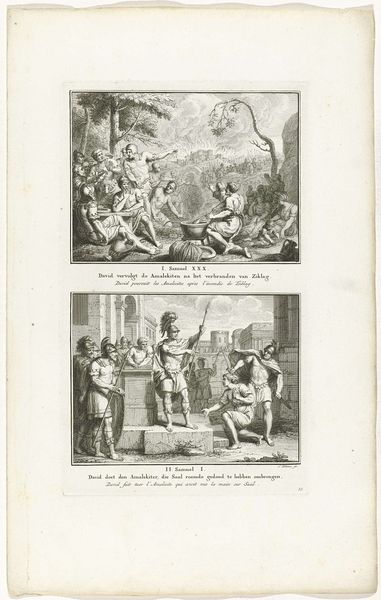

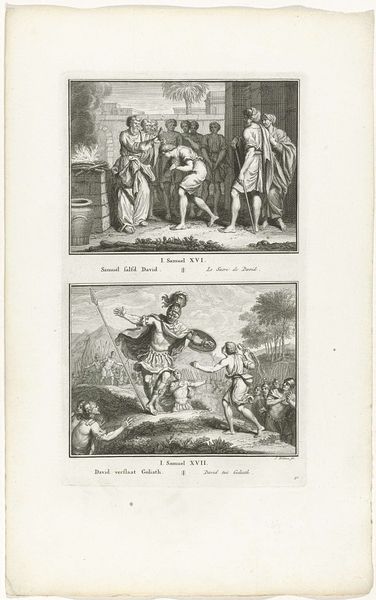

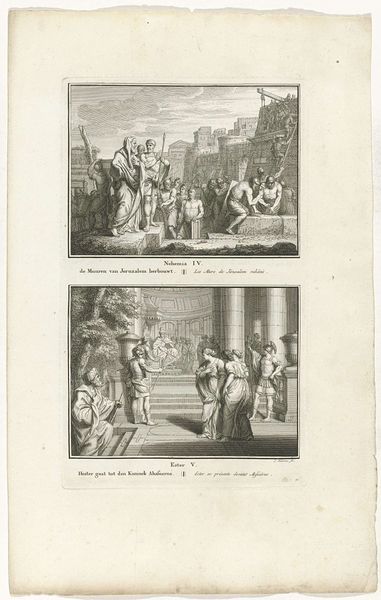

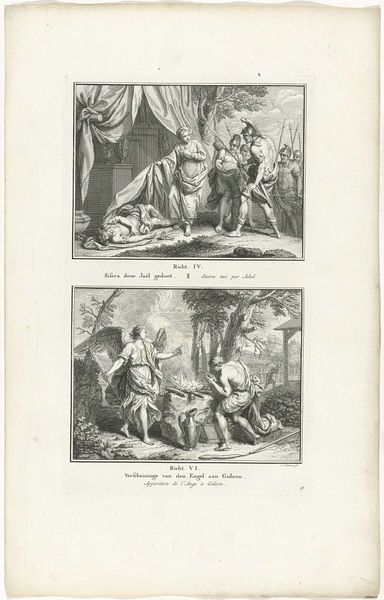

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

orientalism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 338 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

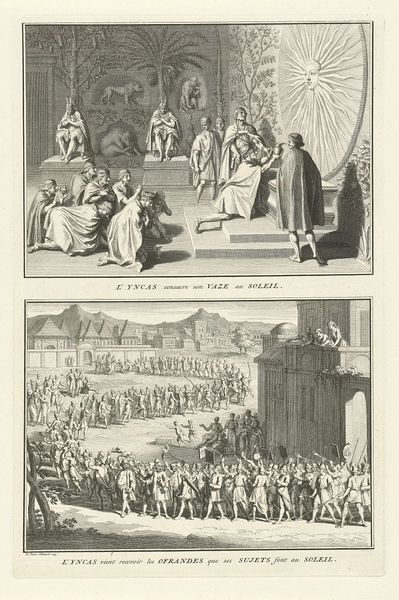

Curator: This engraving by Bernard Picart, dating from 1728, is titled "Tataarse en Chinese priesters," housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately striking is the stark contrast. The figures, rendered in such fine lines, seem suspended between the detailed landscapes of both panels. Curator: Picart used engraving, a process of cutting lines into a metal plate to hold ink. Look closely; the depth and density of lines would have taken immense labor, a real commitment to the craft. The image was made as part of a book called "Ceremonies and Religious Customs of All the Peoples of the World". Editor: Yes, the ritualistic objects—the rosaries, the strange hats—speak volumes. What stories are embedded in those repeated forms? Curator: Consider the socio-political lens. It depicts religious figures from vastly different cultures – a common Orientalist trope during the Baroque era. How were these images consumed? Who had access to these prints? Were they seen as accurate representations or exoticized stereotypes? Editor: Note how the chains bind some figures in the lower register, contrasted by the freer robes of the upper panel’s Tartar lamas. That visual cue begs an interpretation: are these figures imprisoned physically or bound by their religious beliefs as viewed by the European observer? Curator: Precisely. The very act of documenting "the other" underscores the power dynamics at play. The material object—the print—becomes a vehicle for disseminating very particular cultural narratives. The paper itself bears the trace of those processes, from production to circulation. Editor: The careful placement of each figure, too, directs our eye through a very specific visual narrative—one of judgment, of otherness, yet also a peculiar form of admiration or fascination. The faces are carefully individualized, suggesting respect and interest. Curator: We must not romanticize. This image, beautiful as it is, reveals a specific cultural gaze, a particular form of material production embedded within a complex historical landscape. Editor: And these symbols persist, albeit transformed, in how we understand and represent cultures across borders even today. Food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.