Dimensions: Duration: 8 min, 43 sec

Copyright: © William Kentridge | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

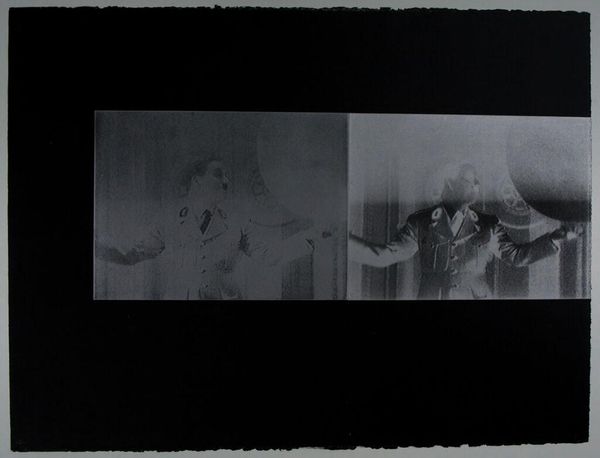

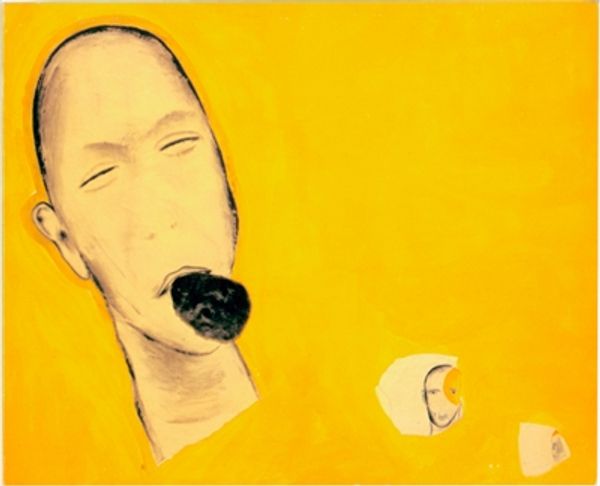

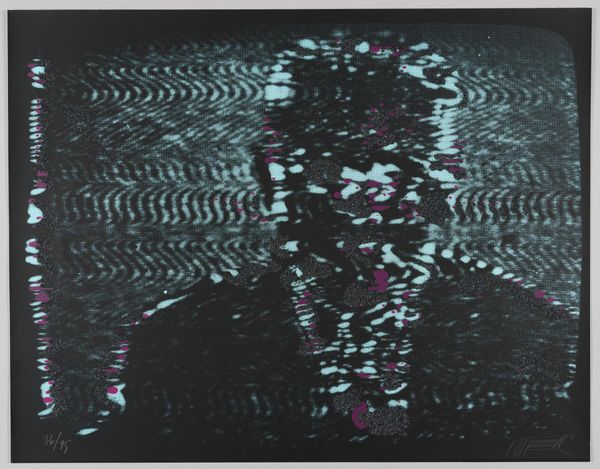

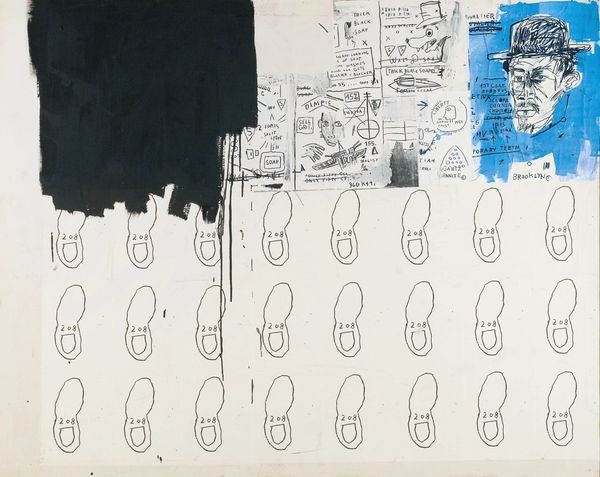

Curator: Here we have William Kentridge’s “Felix in Exile,” a film piece residing in the Tate collection, lasting 8 minutes and 43 seconds. Editor: My first impression? Melancholy. The stark blue palette and fragmented figures evoke a sense of displacement and longing. Curator: Indeed. Kentridge masterfully employs charcoal animation, creating layered images that explore themes of memory, identity, and post-apartheid South Africa. Observe the recurring motifs—the telephone, the landscape—acting as signifiers within a complex visual language. Editor: It feels deeply personal. As if he’s sifting through his own history and trying to make sense of it all, one charcoal stroke at a time. A truly moving piece. Curator: Precisely. The formal elegance belies a profound engagement with socio-political realities. A piece where form meets content with devastating effect. Editor: It leaves you with a lingering feeling, a question mark hanging in the air.

Comments

tate about 1 month ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kentridge-felix-in-exile-t07479

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate about 1 month ago

⋮

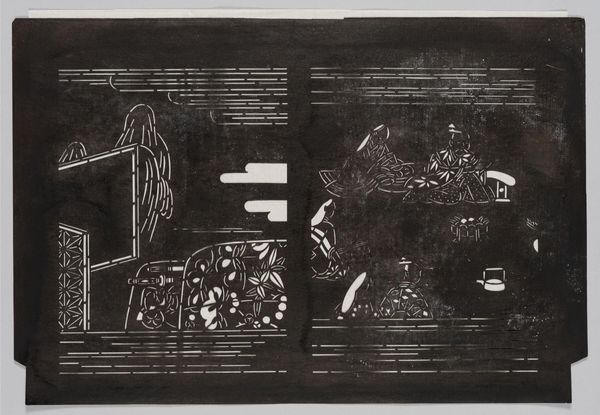

Kentridge makes short animation films from large-scale drawings in charcoal and pastel on paper. Each drawing, which contains a single scene, is successively altered through erasing and redrawing and photographed in 16 or 35mm film at each stage of its evolution. Remnants of successive stages remain on the paper, and provide a metaphor for the layering of memory which is one of Kentridge's principal themes. The films in this series, titled Drawings for Projection (see Tate T07482-5 and T07480-81), are set in the devastated landscape south of Johannesburg where derelict mines and factories, mine dumps and slime dams have created a terrain of nostalgia and loss. Kentridge's repeated erasure and redrawing, which leave marks without completely transforming the image, together with the jerky movement of the animation, operate in parallel with his depiction of human processes, both physical and political, enacted on the landscape. Felix in Exile is Kentridge's fifth film. It was made from forty drawings and is accompanied by music by Phillip Miller and Motsumi Makhene. It introduces a new character to the series: Nandi, an African woman, who appears at the beginning of the film making drawings of the landscape. She observes the land with surveyor's instruments, watching African bodies, with bleeding wounds, which melt into the landscape. She is recording the evidence of violence and massacre that is part of South Africa's recent history. Felix Teitelbaum, who features in Kentridge's first and fourth films as the humane and loving alter-ego to the ruthless capitalist white South African psyche, appears here semi-naked and alone in a foreign hotel room, brooding over Nandi's drawings of the damaged African landscape, which cover his suitcase and walls. Felix looks at himself in the mirror while shaving and Nandi appears to him. They are connected to one another, through the mirror, by a double-ended telescope and embrace, but Nandi is later shot and absorbed back into the ground like the bodies she was observing earlier. A flood of blue water in the hotel room, brought about by the process of painful remembering, symbolises tears of grief and loss and the Biblical flood which promises new life. Kentridge has commented: 'Felix in Exile was made at the time just before the first general election in South Africa, and questioned the way in which the people who had died on the journey to this new dispensation would be remembered' (William Kentridge 1998, p.90). In this film Nandi's drawing could be read as an attempt to construct a new national identity through the preservation, rather than erasure, of brutal and racist colonial memory. Further reading:Dan Cameron, Carolyn Cristov-Barkagiev, J.M. Coetzee, William Kentridge, London 1999, reproduced (colour) pp.66-7, 122-7Carolyn Cristov-Barkagiev, William Kentridge, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1998, pp.90-9, reproduced (colour) pp.91-2, 94-5, 99, (detail) p.89Elizabeth Manchester February 2000