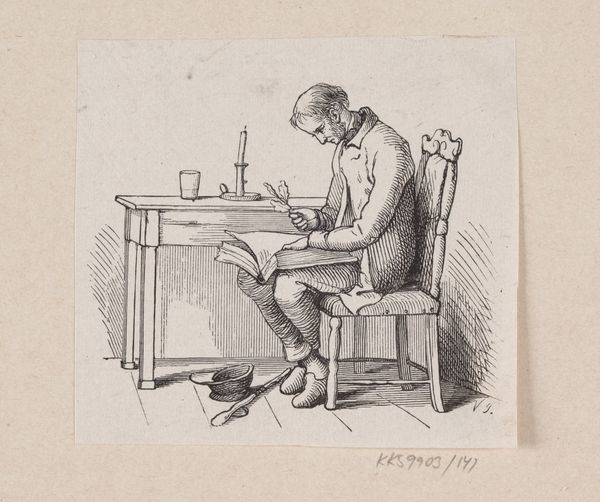

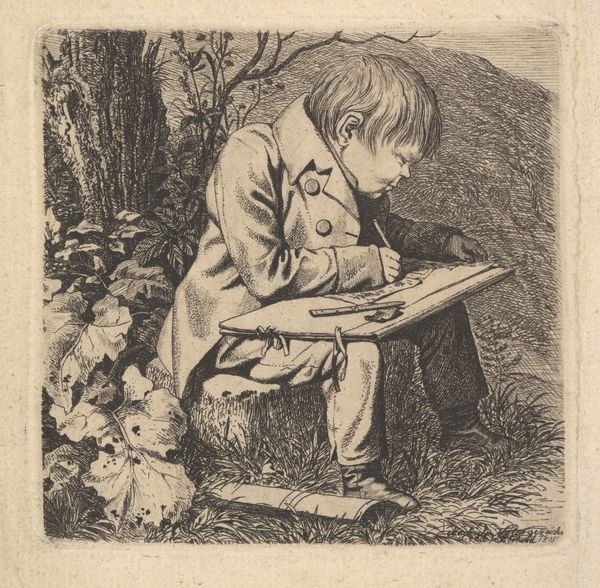

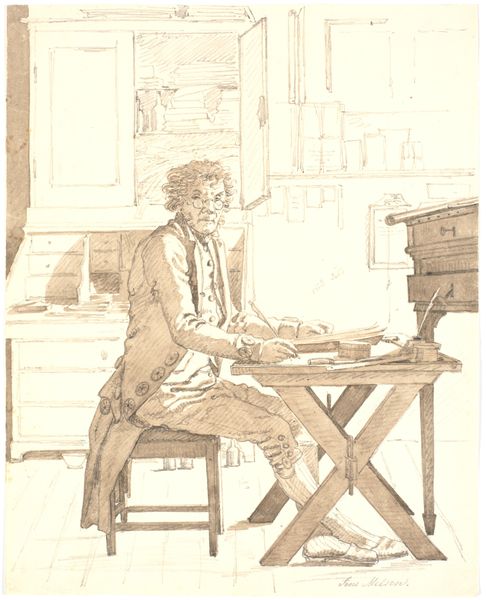

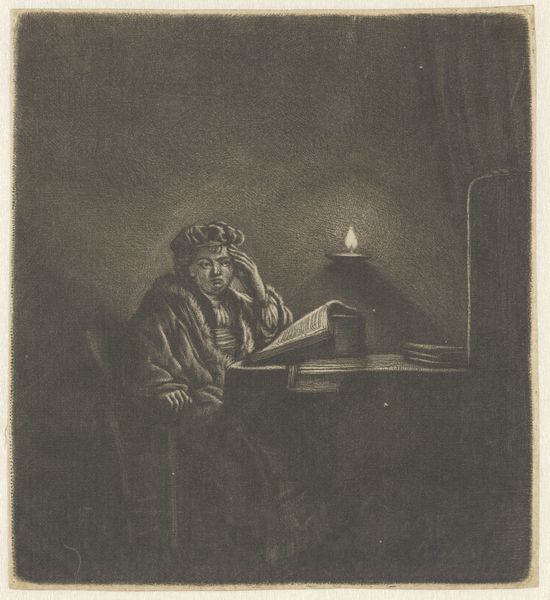

A Young Man Seated at a Desk Writing 18th-19th century

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphite

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

yellowing background

#

parchment

#

wood background

#

warm toned

#

yellow element

#

france

#

warm-toned

#

graphite

#

golden font

#

gold element

Dimensions: 4 11/16 x 4 11/16 in. (11.91 x 11.91 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "A Young Man Seated at a Desk Writing" by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, estimated to be from the 18th to 19th century and residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. A graphite drawing, I find the details to be striking, even now. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the softness of the lines. It’s graphite on toned paper, I see. It’s almost like witnessing a fleeting moment, a quiet scene carefully rendered. I can almost feel the weight of that paper and its yellowing history in my hands. Curator: That's an interesting observation. I'm drawn to the institutional aspect, thinking about the act of writing in this period. Who was allowed to write? What kinds of narratives were encouraged and, more importantly, which were suppressed? Prud'hon’s subject likely represents a particular societal stratum. Editor: Absolutely. The materials tell their own story, don’t they? Look at that warm toned, almost parchment-like quality, the simple quill, the wooden desk. Each object speaks to a mode of production, of available resources, reflecting the craftsmanship of the time and, by extension, the class implications. The soft golden lines further emphasize the refinement of it all. Curator: The drawing embodies a tension prevalent during that era—between the burgeoning ideas of individual expression and the strict social structures that governed much of daily life. Is he writing a love letter, or perhaps fulfilling an obligation? Is his posture and appearance suggesting self-empowerment or social expectation? Editor: Exactly. Consider how labor is represented here – the focused, solitary act of writing, seemingly romantic, yet it is a kind of labor. Is he self-employed? Is it skilled work, commissioned work? These factors condition both how Prud'hon created this image and how it might have been interpreted. It makes me consider the young man's potential social mobility or lack thereof. Curator: Looking at the circulation of such an image is also of great importance, wasn’t it? How might engravings have allowed this image, and therefore these socio-political attitudes, to spread beyond the immediate aristocratic circle? Editor: Ultimately, I think the drawing serves as a gentle reminder of how intimately bound our lives are with the tools and materials we use, even when engaged in the seemingly solitary act of writing. Curator: I agree; this gives us a poignant snapshot into the layered complexities of an era defined by both tradition and revolution.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.