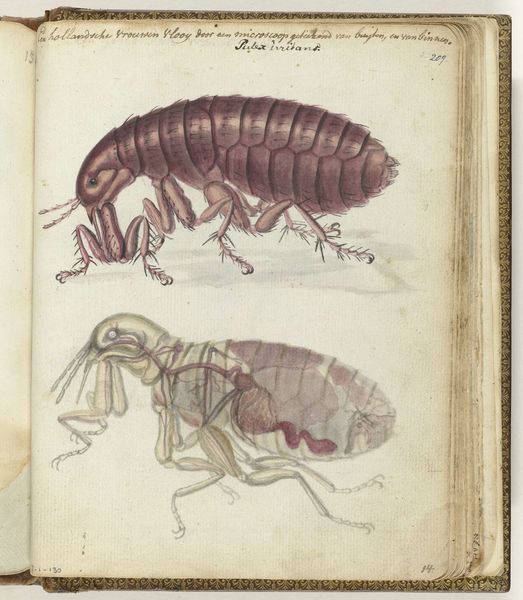

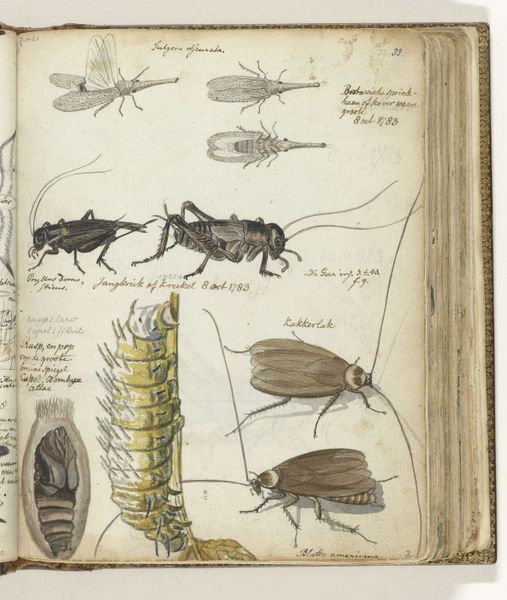

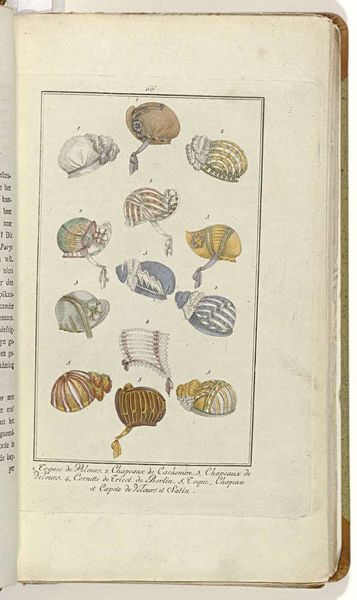

drawing, watercolor

#

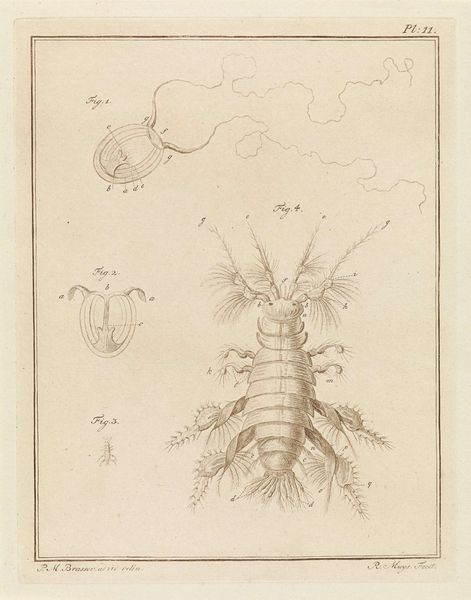

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

personal sketchbook

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

naturalism

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

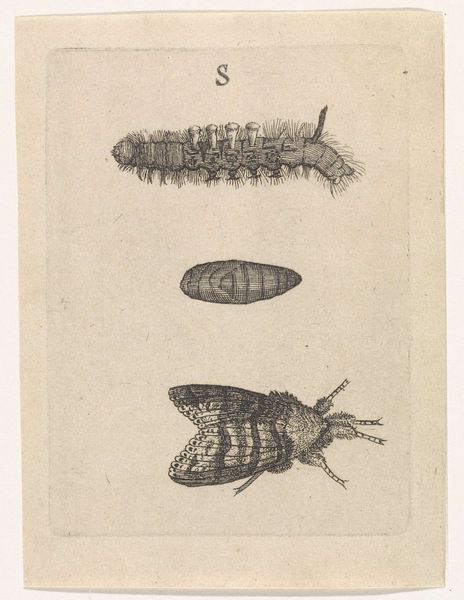

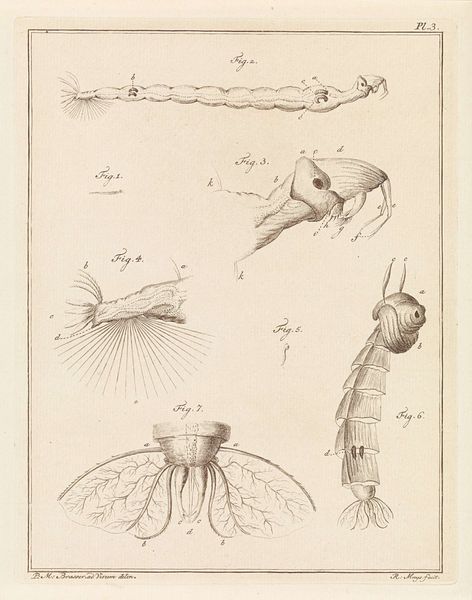

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

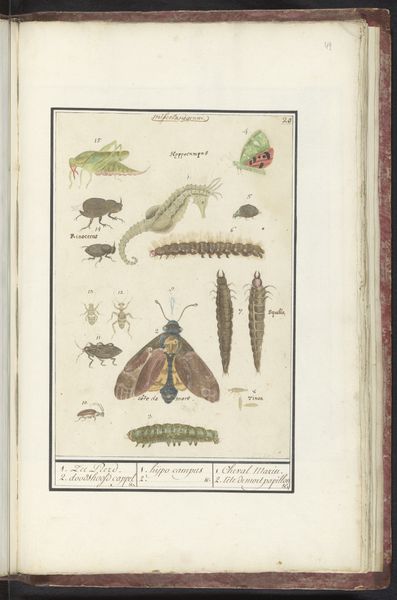

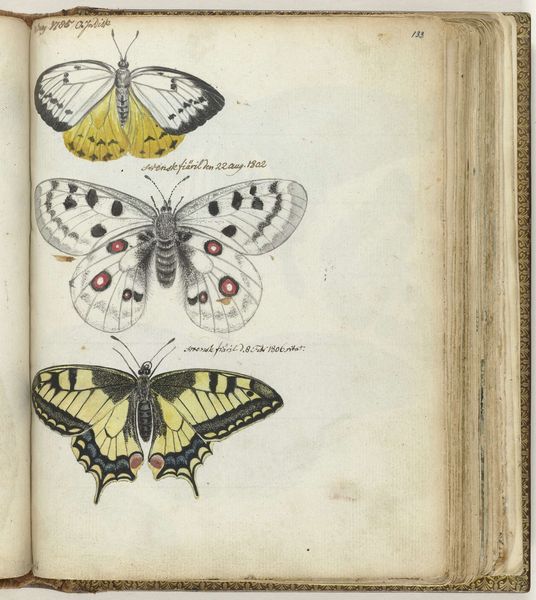

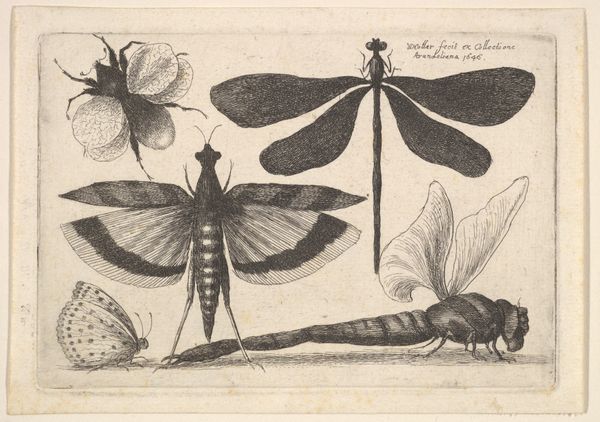

Editor: Here we have "Champignonswormen," possibly from 1770-1787, by Jan Brandes. It's a watercolor and drawing on aged paper – it gives me the feeling of looking into an old naturalist’s journal. The details are fascinating! What can you tell me about it? Curator: This image is fascinating precisely because of that feeling it evokes – the intersection of art, science, and societal understanding of the natural world. Brandes presents a scientific study, yet the artistry shapes how that study is received. Consider, for instance, the inscription above the sketches. What does it tell you about the artist's intentions? Editor: I see... it mentions microscopes and the metamorphosis of "worms" into "kevw"... I think that’s "kevers" – beetles – in Dutch. It sounds like he's trying to scientifically document these creatures. Curator: Exactly. And the decision to use watercolor is significant. Why not simply describe them in words? Visual representation carries an authority, lending credibility to Brandes' observations. It was, in essence, a means of disseminating knowledge within specific social circles. Editor: So it's less about purely artistic expression and more about scientific communication embedded within the social norms of the time? Curator: Precisely. Think about the role illustrated journals played in spreading new discoveries. The visual element served both as evidence and as a persuasive tool, especially crucial in convincing others of new ideas about the natural world. Editor: I never thought about how much the artistic choices impacted the science itself. Now I'm looking at it as a window into how people learned and shared knowledge then. Curator: Indeed. And how art actively shaped that process, solidifying certain perspectives within a larger cultural narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.