#

pencil drawn

#

aged paper

#

photo restoration

#

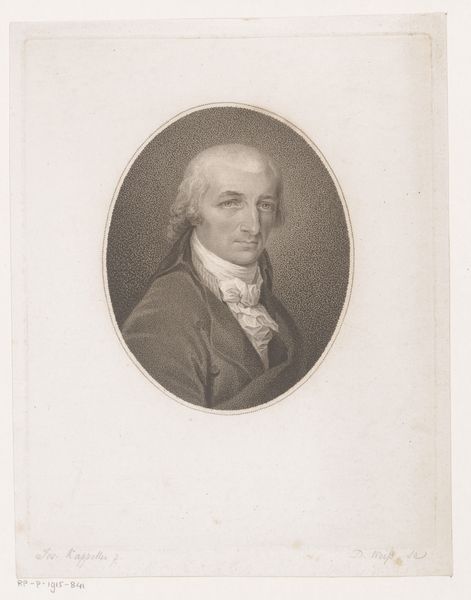

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

old-timey

#

yellow element

#

19th century

#

portrait drawing

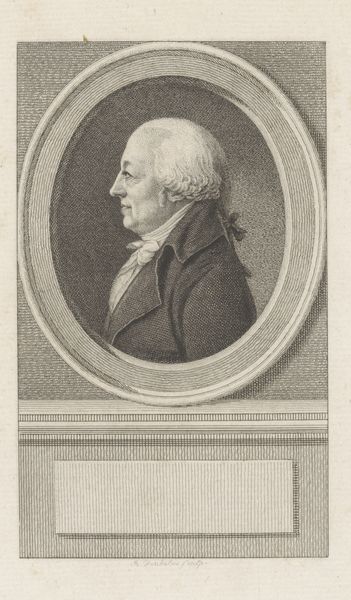

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 69 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

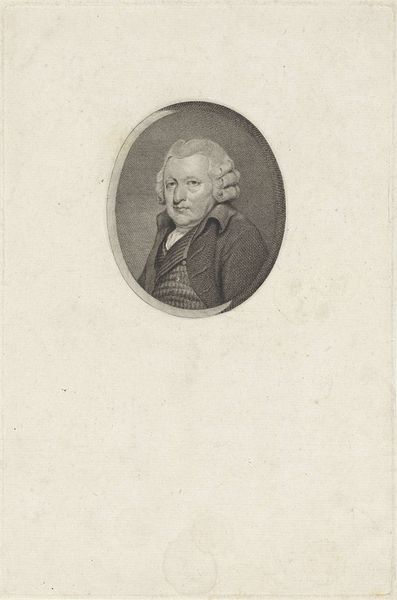

Editor: We're looking at "Portret van Martinus van Marum" by Gilles Louis Chrétien, dating from around 1785 to 1811. It appears to be a portrait drawing, very detailed despite its age. I’m struck by the sitter's gaze, directed away as if contemplating something. What do you see in this piece beyond just a historical portrait? Curator: This isn’t just a portrait; it's a window into the Enlightenment's project of reason and the scientific revolution. Martinus van Marum was a pivotal figure in popularizing science, and Chrétien, through his Physiognotrace – a machine-aided drawing technique – democratized portraiture. The crisp lines, born of technology, reflect the Enlightenment’s emphasis on empiricism. Consider who had access to portraiture previously and what this shift signifies in the context of emerging bourgeois power structures. How might this connect to discussions around access and representation today? Editor: That’s fascinating, the intersection of art and technology as a form of democratisation. So you’re saying the *how* is as important as the *who*? Curator: Exactly! It forces us to consider representation and accessibility, particularly how these advancements served or challenged the existing social order. Think about Van Marum, not just as a subject, but as part of a burgeoning scientific class. Was his portrait simply an act of documentation, or something more akin to constructing a particular identity for that class? Who was this art for? Editor: I never would have considered all those layers just by looking at the image. It definitely shifts my perspective, viewing the portrait more as a cultural statement than just a depiction of a man. Curator: Precisely! It is through considering such context that we may start thinking critically about portraiture – its cultural function, and potential biases, both then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.