Copyright: Public domain

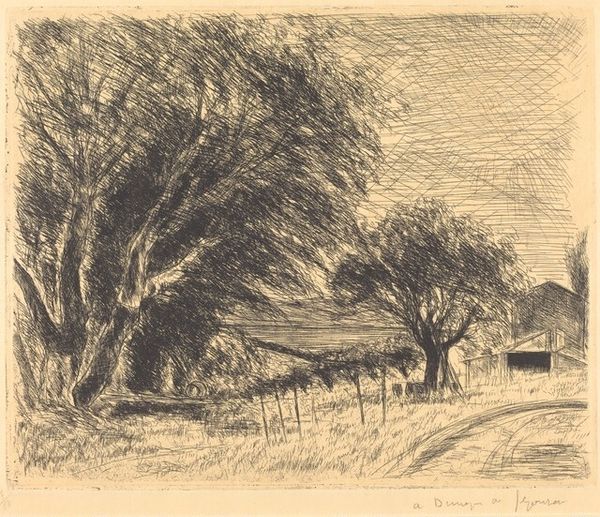

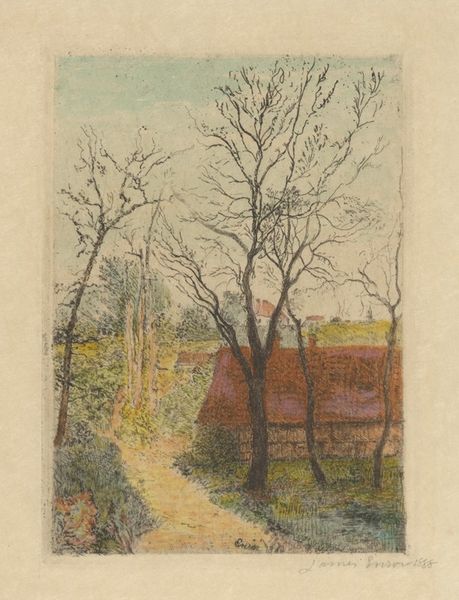

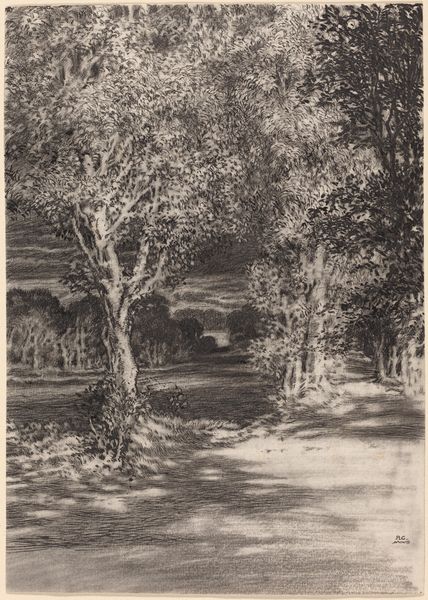

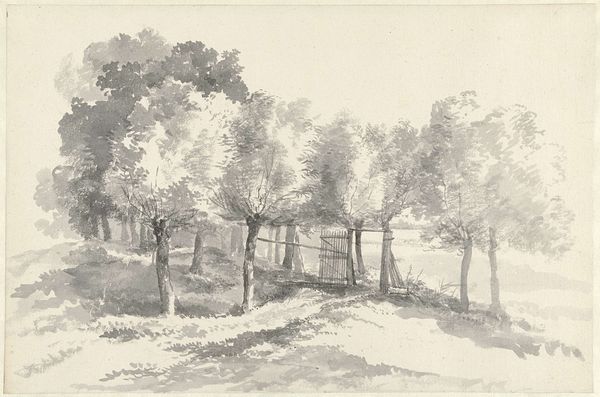

Curator: This painting by Camille Pissarro, created in 1883, is titled "Landscape at Osny near Watering," offering us a glimpse into the French countryside during a time of significant societal shift. Editor: It strikes me immediately as quite romantic, in a subdued way. The trees frame the village scene, softening the edges of daily life. There's a delicate balance of light and shadow, making it feel like a half-remembered dream. Curator: Exactly, there's that dreamlike quality typical of Impressionism. The artist’s approach to light really showcases an emerging social and environmental consciousness that prized landscapes such as this. We begin to see rural France not just as fields to be farmed, but places that are valuable because of their untouched qualities. Editor: I see that romantic pull, yes. Trees, for instance, serve here almost like figures—witnesses of a pastoral past but also emblems of time, longevity and steadfastness, wouldn’t you say? They also hint to ecological ideas, even in their most nascent state. Curator: Definitely. Pissarro utilizes the natural environment here to signal stability amidst the rapidly modernizing 19th-century France. The figures walking along the path seem completely ordinary. However, even they become a symbol of rural life and the importance of tradition in the face of social change. Editor: Right, that path becomes a connective thread between the land, the people and those enduring cultural symbols such as cottages, groves and hamlets, so present in folk narratives of the period. Curator: That connection underscores the idealized view of peasant life prominent at the time. By employing painting en plein air—capturing fleeting light and atmospheric conditions—Pissarro participates in a long lineage of romanticizing natural scenery to offer social and moral guidance. Editor: I see that as well. And by returning to nature, to those traditional tropes in visual art, he offers viewers a perspective through which to imagine and hopefully preserve threatened traditions and images from collective memory. Curator: Perhaps even to offer an idyllic symbol as reassurance that those rural rhythms persist as others continue to grow increasingly chaotic. Editor: I think that’s it precisely; he asks us what it means to see—and preserve—an image that gives permanence to something passing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.