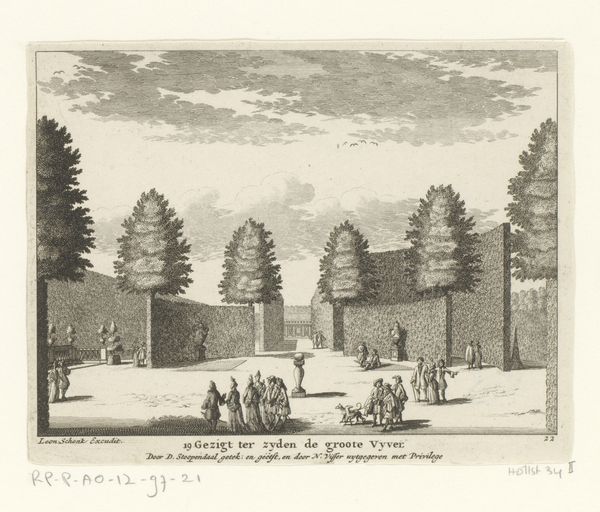

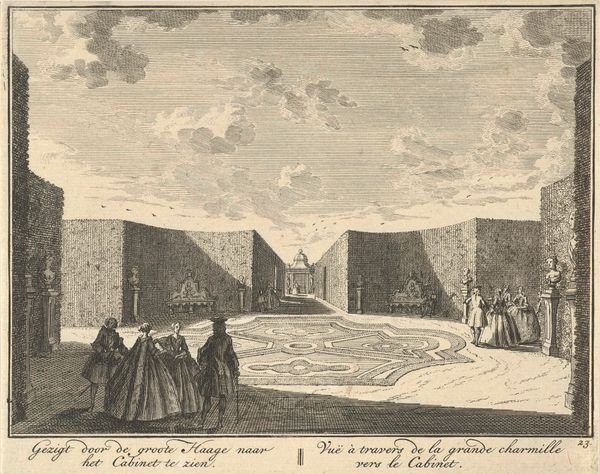

Gezicht op de vijver vanaf de zuidzijde op landgoed Clingendael Possibly 1689 - 1746

0:00

0:00

laurensscherm

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 128 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately about this engraving, "Gezicht op de vijver vanaf de zuidzijde op landgoed Clingendael," is how it captures a moment of societal performance. The figures, positioned meticulously, seem to be engaged in an elaborate dance of social rituals, echoing larger power structures at play. Editor: It feels oddly staged, doesn’t it? The rigidity in the architecture and the posture of the figures suggests a carefully constructed display, even if the scene purports to be natural. I’m interested in the means of producing that effect, especially considering this is an engraving—what labour was involved? Curator: Precisely. Understanding the social and historical context—the fact that this was likely created sometime between 1689 and 1746 by Laurens Scherm, for wealthy landowners to enjoy this cultivated natural settings - informs how we view the carefully managed composition and also the representation of leisure. Editor: It does read as promotional material. This wasn't just an engraving made for pleasure; the means of producing and circulating this work served to uphold the power dynamics. This "Clingendael" isn't just a place; it's a carefully crafted symbol. I'm sure making all those repeated lines that create depth took a fair while! Curator: Consider, too, who had access to leisure in that era. Who could afford such a manicured landscape? It reinforces the elitism of the period, even in what appears to be a pastoral scene. The placement of figures—their costumes, their interactions—these all hint at a social hierarchy being both enacted and reinforced. What messages are conveyed by that small dog? Editor: Ah, the ever-present accessory. I’d bet good money there's symbolic capital invested in that small canine companion. And thinking about the means to reproduce that artwork to distribute amongst potential clients or similar… That alone must be considered the first promotional material, I suspect! Curator: Examining it through that lens lets us unpack a deeper narrative beyond the picturesque façade. It invites dialogue on identity and class. It brings art history together with the sociology and economy of its era. Editor: Yes, by examining the labour and material implications in tandem with its social milieu, this becomes more than a landscape engraving; it is now a key material artifact revealing truths of power and representation. Curator: It reminds us that what may seem like a serene snapshot is really embedded in societal narratives about aspiration and social status. Editor: I leave thinking about how the creation of that scene involved people: both in front of, and behind the production, each with an economic agenda or position. It is no wonder it ended up at the Rijksmuseum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.