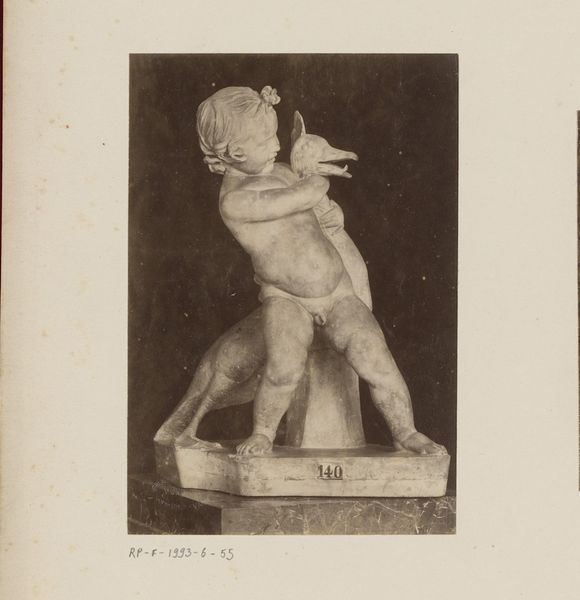

bronze, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

classical-realism

#

bronze

#

figuration

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

nude

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

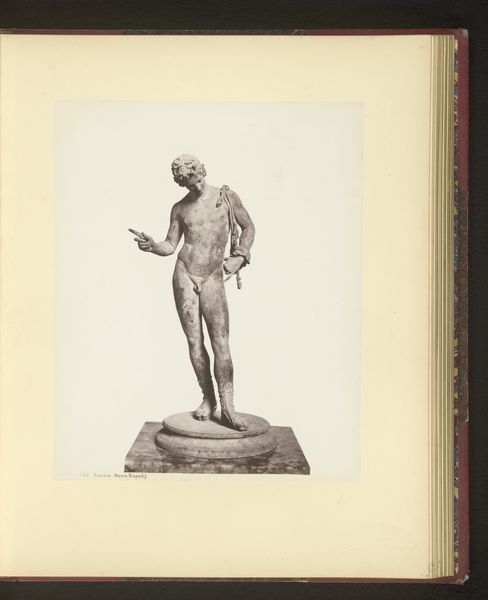

Curator: Ah, here's a photograph taken by Giorgio Sommer before 1879, now held in the Rijksmuseum collection. It's a gelatin silver print depicting a bronze sculpture titled, "Bronzen sculptuur van een slapende sater," or "Bronze sculpture of a sleeping satyr." Editor: Well, immediately I feel a sort of languid peace. He looks almost too relaxed to be a satyr! I picture sunshine dappling through leaves...it makes me want to take a nap, honestly. Curator: It's fascinating to consider how the photograph itself influences our perception of the sculpture. Sommer’s choice of lighting and the gelatin silver print medium certainly contribute to that sense of classical repose you're describing. We're seeing the sculptural tradition of representing idealized forms, but through a relatively new photographic process. How would its meaning shift in mass production for sale in print form? Editor: That’s true. Photography flattens the bronze; steals a bit of its heft, makes it less imposing somehow. More…accessible? One wonders about the intentions, of using the new medium for distribution of existing artworks. I almost want to touch the photograph and feel for the bronze. Curator: And the circulation of these images definitely democratized access to classical forms. Though, let’s remember that this was a highly staged affair. Think about the labor: from mining the ore to creating the bronze, to Sommer carefully posing and lighting the sculpture, and then, the printing process itself! Each step imbues it with value. Editor: Good point! Thinking of labour and context, and those cheeky satyrs do come from mythology about earthly pleasures...is it meant to celebrate pleasure, and perhaps idleness, even in labor? Now, you've really set my mind off... What kind of workshops, and patronage enabled all these art processes from mining, production to distribution and sales in photo print forms! Curator: Exactly! It's all these questions we must constantly address. The circulation and creation depended on the access and investment across each production aspect, Editor: Makes me think about who bought it. They saw him! What does their sleep look like. Hmm. Curator: Ultimately, this image gives us an insight not just into ancient narratives but also into the cultural and economic networks operating in the 19th century, bridging craft and capital. Editor: Agreed. I'm taking away the ripple effect: it makes you think what "sleep" truly means across forms: sculptural representation, lived-in act, captured-photo sales... the distribution truly allows us to think differently now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.