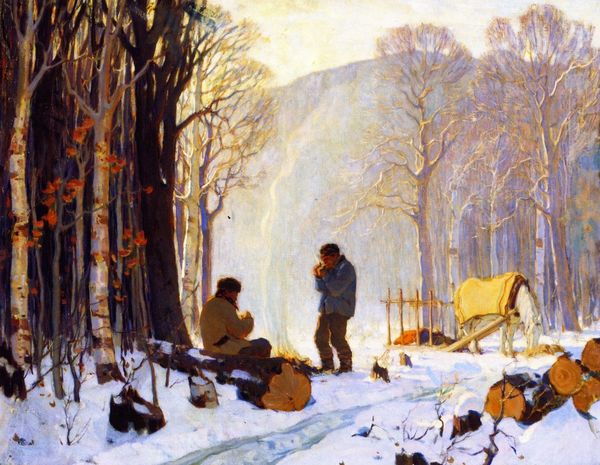

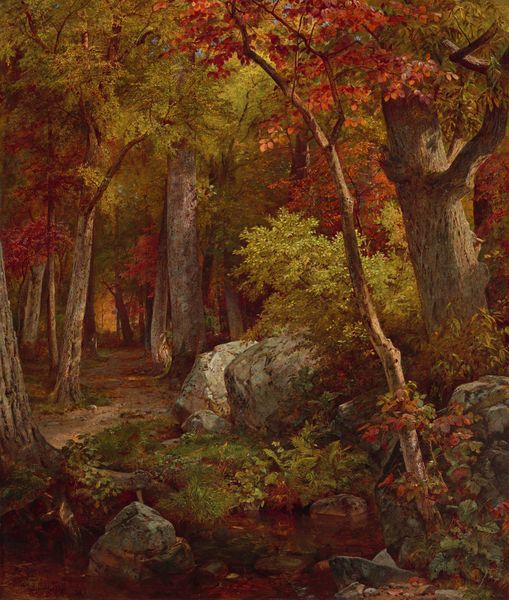

Copyright: Public domain

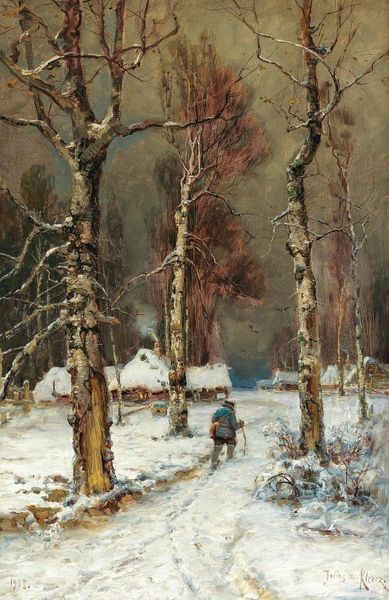

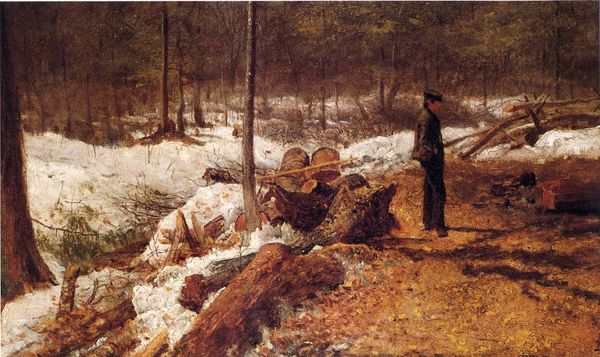

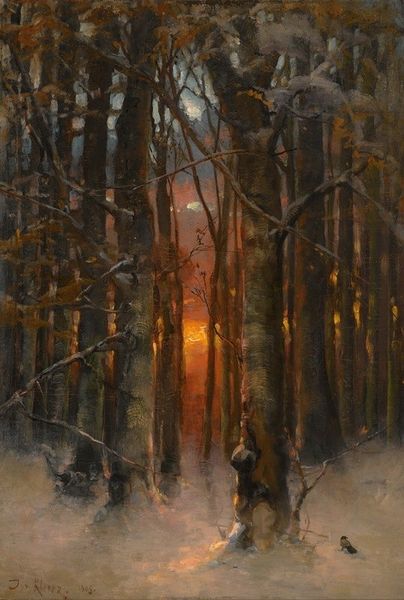

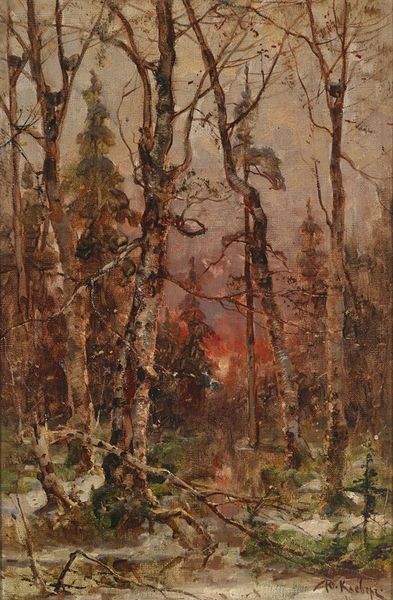

Curator: Albert Bierstadt’s “Moose Hunters Camp,” painted around 1880, is a captivating example of the Hudson River School style, rendered in oil on wood. What strikes you most upon viewing it? Editor: Immediately, the contrast arrests my attention—the chiaroscuro effect as it's often called—how the warm light seems to emanate from the camp while darkness pervades the surrounding forest. It is such a dramatic arrangement. Curator: Absolutely, this work speaks volumes about the era's fraught relationship with the American landscape and westward expansion. Consider the Indigenous people who are clearly absent from the idyllic hunting scene depicted here. The presence of the hunters becomes emblematic of both exploitation and, I daresay, colonial dispossession. Editor: That’s certainly a compelling interpretation, though I can't help but focus on Bierstadt’s skillful application of texture— the dense, impasto strokes rendering the bark of the trees, for instance. These compositional techniques convey a feeling of immediacy that goes beyond any imposed narrative about colonialization. The painting's organization follows a precise dichotomy. Curator: But we cannot separate technique from its broader context, especially in the 19th century when landscape painting became entangled with manifest destiny. Bierstadt, in crafting what seems to be a picturesque moment, participated in an aesthetic tradition that romanticized and consequently facilitated colonial expansion into the supposedly unoccupied land. He was a crucial element of that symbolic restructuring of place. Editor: Still, there’s a mastery in how Bierstadt guides our eye through the interplay of color, form, and brushstroke. This kind of precise design adds an independent significance beyond simple documentary function or politically engaged intention. I believe it transcends historical conditions through these more subtle techniques. Curator: But the composition serves Bierstadt's specific political vision, right? Note how small the figures are compared to the forest. It diminishes their agency while subtly legitimizing human domination over nature through acts like hunting for sport. What is omitted, therefore, says even more about colonial attitudes toward landscape. Editor: Fair enough. Curator: The piece acts as a loaded representation that has reverberations for understanding both past and present encounters concerning cultural appropriation. Editor: Precisely, even if you foreground those socio-historical interpretations, one cannot deny the enduring formal brilliance through his ability to use landscape design.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.