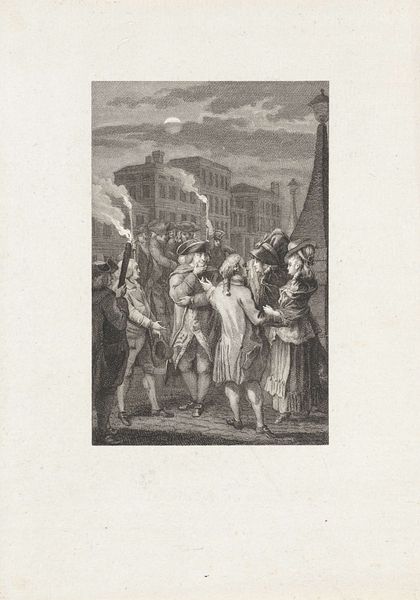

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

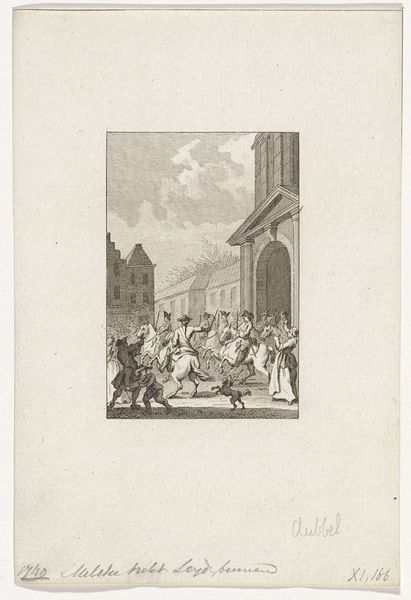

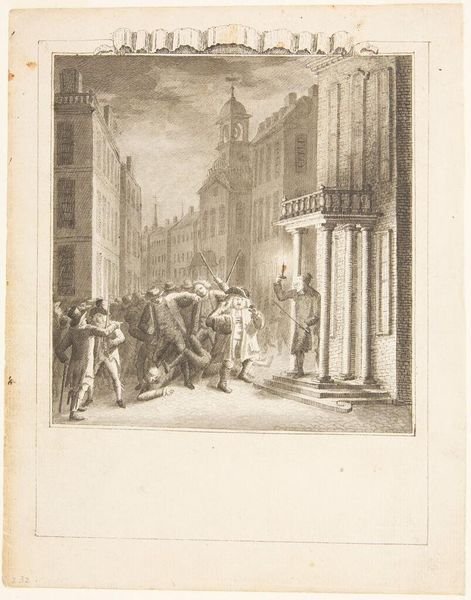

Curator: This print by Reinier Vinkeles, titled "Plunderende Oranjeklanten te Delft, 1787," pulls no punches. Created in 1796, it shows us a pretty brutal scene in Delft. The medium is engraving, emphasizing line work that’s just teeming with a frantic energy. Editor: Wow, "frantic" is right. My first thought? Chaos. Just pure, unadulterated chaos erupting in what seems like a quiet, orderly Dutch city. You almost expect sound to blast from it, shouting and smashing. Curator: Exactly! It’s an image deeply rooted in its historical moment. "Oranjeklanten" refers to supporters of the House of Orange, and this depicts them looting in Delft during a period of political upheaval. Vinkeles is making a clear statement about the violence perpetrated by this faction. It reflects how charged everyday life could be when revolutionary politics touched ordinary homes. Editor: It's strange to think of the Dutch Golden Age, so synonymous with still life, Rembrandt and Vermeer, also birthing imagery of public upheaval like this. And to depict violence so starkly, right there amidst those lovely buildings with such rigid order--the spire in the background adding a silent, godly approval... disturbing. Curator: The contrast is striking, isn't it? The clean lines and almost idealized cityscape in the background clash brutally with the foreground’s raw depiction of violence. Vinkeles places us right in the thick of things. You can almost feel the tension, the fear, and even the bloodlust in the crowd. It speaks volumes about the polarization of Dutch society at that time. The work really uses perspective to create a very claustrophobic, anxious sense. Editor: You see so many historical prints that romanticize a time, turning conflict into grand narrative or heroic scenes. There's a realism, or almost anti-heroic stance, in Vinkeles that gives a more urgent, personal message. I think that almost crude, immediate effect lingers longest, actually, more than the wider political history that it portrays. Curator: I agree entirely. The engraving leaves an uncomfortable feeling; even after years, it can still jolt one out of historical detachment. Editor: Right! What stays with me most is that raw, visceral feeling and question-- what is order in this world, really?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.