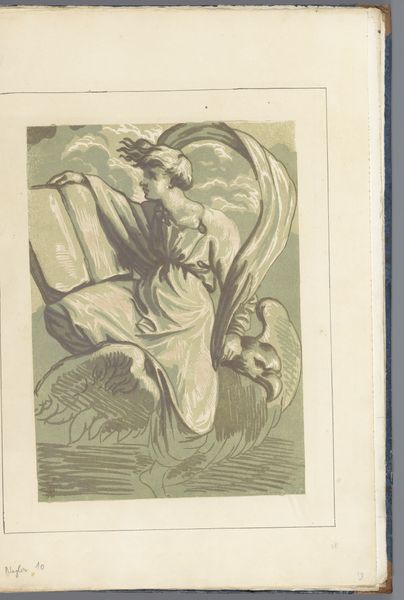

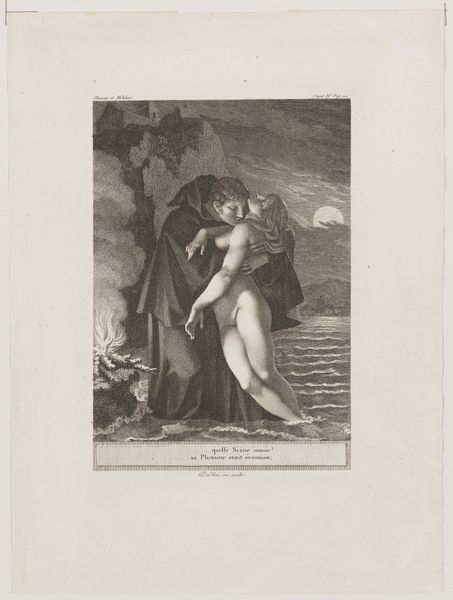

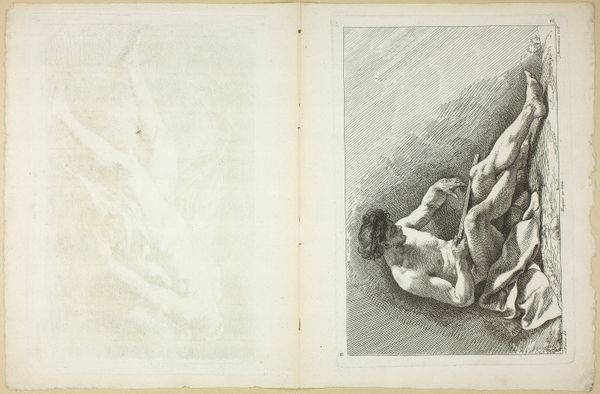

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

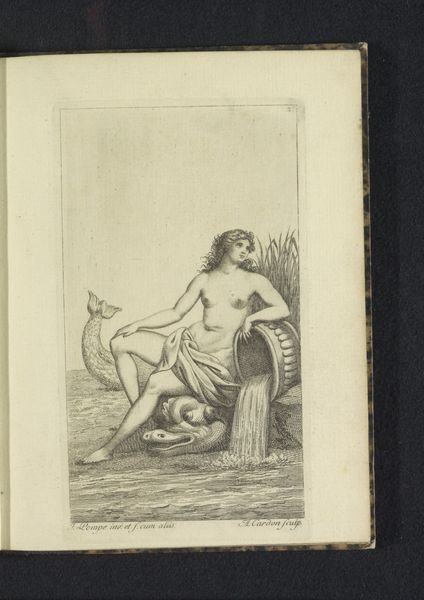

Curator: Oh, this drawing just charms the socks off me. It’s entitled "Kinderen met een adelaar," or "Children with an Eagle," made between 1772 and 1773 by Antoine Alexandre Joseph Cardon. You can find it nestled in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. What leaps out at you? Editor: The immediate thing is that it has this quality that many drawings and engravings of the period have which, for want of a better term, I would call hyper-whiteness. There’s this strange emphasis on pale figures set against an airy, delicate background. But these whiteness aesthetics become so loaded when we start unpacking power and the gaze… Curator: I get that. But, purely as an artist, there’s a playful freedom in the sketchiness. Cardon isn't trying to replicate reality. Those chubby children wrestling the somewhat bewildered eagle feel like a delightful daydream. It feels, for me, somehow revolutionary for its lack of seriousness! It knows exactly what it wants to be: a fleeting thought. Editor: A fleeting thought brimming with the colonial fantasies so enmeshed in that period, though! These children with the eagle echo so much that was then being depicted that helped uphold this racial hierarchy in which the white subject is constructed as free and naturally innocent... Think about it: why are we focusing so intently on *these* children's game, and *this* idyllic scene of beauty in nature, when across oceans and lands this idea was actively denied? Curator: Well, I also see the kids and the eagle as figures within Romanticism's broader project: challenging hierarchies between humankind and nature, even if tinged with ideologies that we must acknowledge are problematic to the modern eye. What’s lovely is this idea of childhood innocence—they believe they have this eagle on their side. Editor: "Innocence" is such a dangerous construct! Even the composition places these figures high up overlooking a tiny waterfall that in and of itself also operates as a symbol of natural power and colonial expansion. Even in art we're not allowed to assume that people thought, and still think, within bubbles of meaning. We live under the consequences of history; this history lived in them as it does in us. Curator: Alright. Alright. I see your point. I'll try and let the children enjoy themselves. Next time, remind me to pick an artwork featuring snarling monsters. Thanks for setting me straight. Editor: It's not about setting you "straight"! I loved delving deeper; it just demonstrates how relevant historical images still are today! Let's make this dialogue a moment of awakening.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.