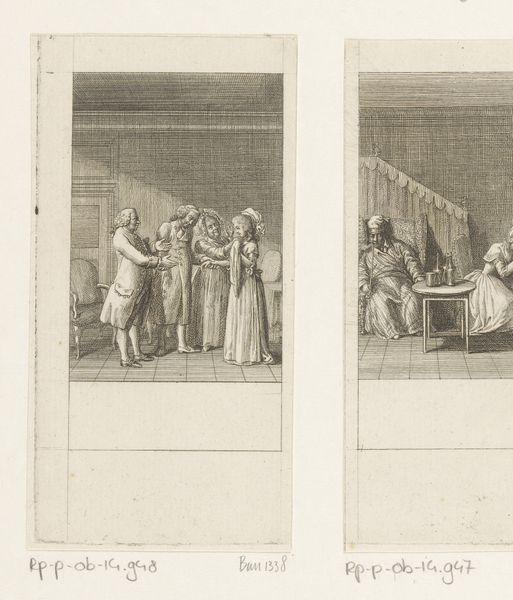

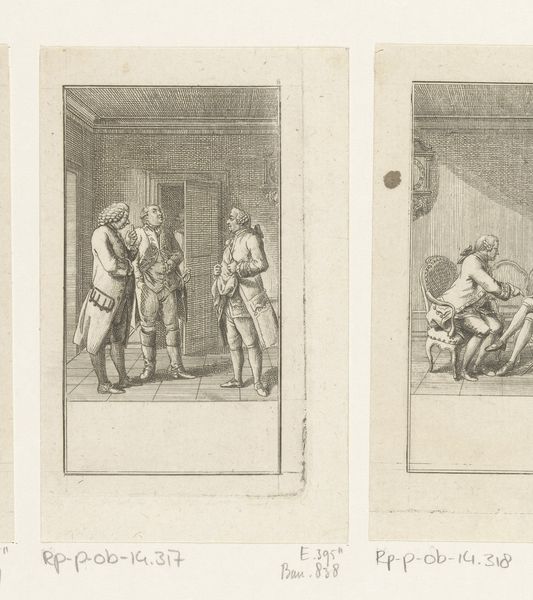

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Musefeld Bekeert Zijn Vader," an engraving crafted in 1788 by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your first impression? Editor: Grim, intimate. I’m struck by the density of the linework, almost like looking through a veil. And there’s this overwhelming feeling of domestic tension in both scenes—something unresolved. Curator: Interesting observation. Chodowiecki produced this print within a charged socio-political atmosphere. Religious and familial authority were both under intense scrutiny. These scenes, seemingly simple domestic dramas, participate in wider debates about Enlightenment ideals versus traditional values. The home becomes a site for ideological struggle. Editor: The title suggests a conversion, but what is being converted into what? Is it just faith? In the first panel, we see the son almost lecturing his father, an imposing figure even seated, a symbol of ingrained tradition perhaps resistant to change. And on the right the figure reclining like a pasha… What is being rejected? Curator: Precisely. Consider the dissemination of prints in the 18th century. They democratized imagery and, consequently, ideas. Chodowiecki wasn't simply depicting a scene but entering a conversation with the public about reformation. Furthermore, notice the architectural space— confined. It reinforces the idea that the conversion or negotiation between faith and authority is personal yet public. Editor: It's intriguing how he employs clothing to subtly depict social class too, isn't it? There's a simplicity and directness in their garments but look also for some markers of rank in the robes draped over the seated figure. The symbol becomes about more than faith, it starts touching on social and political changes too. Curator: The lack of colour enhances that sharp black-and-white duality – obedience versus individual thought; traditional order verses burgeoning liberal perspectives. Editor: You’re right, it adds layers of meaning that extend beyond religious belief to social and ideological transformations in general. I initially focused on the emotional claustrophobia. Curator: Which highlights the powerful combination of image, and context that define what this scene, initially so intimate, means on a broader stage. Thank you for exploring those ideas! Editor: My pleasure! I am keen to keep this reading as an open conversation on domestic revolution and those private, shared public values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.