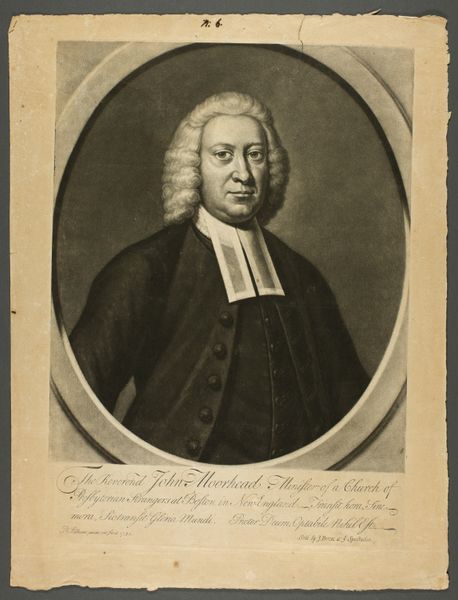

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

historical photography

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

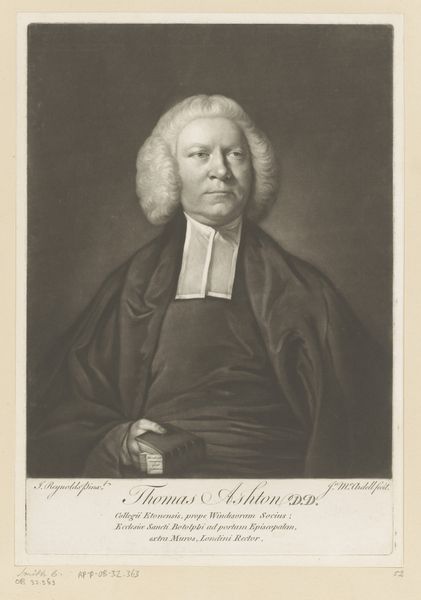

Dimensions: height 326 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

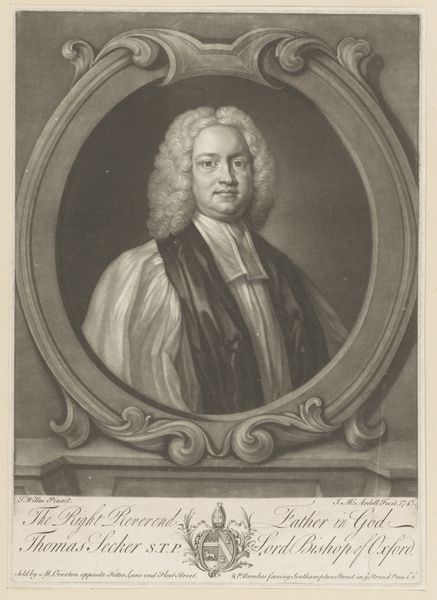

Curator: Here we have James McArdell’s engraving, “Portret van Emanuel Collins,” dating back to somewhere between 1745 and 1765. It’s currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Ah, a very proper gentleman of the cloth. The mood is stately, wouldn't you say? Look at that wig – like a cloud settled upon his head. It reminds me of the opening scene in "Barry Lyndon" actually; there's the same air of restrained, almost theatrical gravity. Curator: It’s important to remember that McArdell didn’t work in isolation. The making of this engraving depended on networks of patrons, print sellers and distributors to bring it to the market, in an era where prints made images widely available and popular, driving consumer demand for reproductions of influential or well-known people like Emanuel Collins. Editor: True, but the engraving style also adds a unique layer. Those delicate lines giving weight to both his clerical status, and the suggestion of humour too... notice the cheeky glint in his eye, juxtaposed with the imposing robes? Curator: Exactly. Engravings like this allowed for a democratization of portraiture, extending visibility to figures like Collins, though consumption remained tied to specific socio-economic means of course. It prompts us to ask about printmaking's role in disseminating and reinforcing ideas about class and power at this time. Editor: So, a printed reproduction, once removed from the subject, can become more accessible, yet ironically enhances and memorializes their position...a tangible ghost in circulation, almost? It also encourages close looking. What hidden narratives can we unpack from this lone, copied image? Curator: Indeed, looking beyond the depicted figure, consider the very material: paper, ink, the labor involved in the printing process. Who made the paper? What were the working conditions? How were these prints marketed and sold, and consumed? All play their part in completing our picture of the world from which this portrait was made. Editor: That's intriguing...almost a ghost within a ghost then. Something solid emerges from shadows, making it timeless! What are we to make of its strange presence still? Curator: It's an engaging artifact, offering glimpses into 18th century society while making us question what we regard as 'fine art' at that time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.