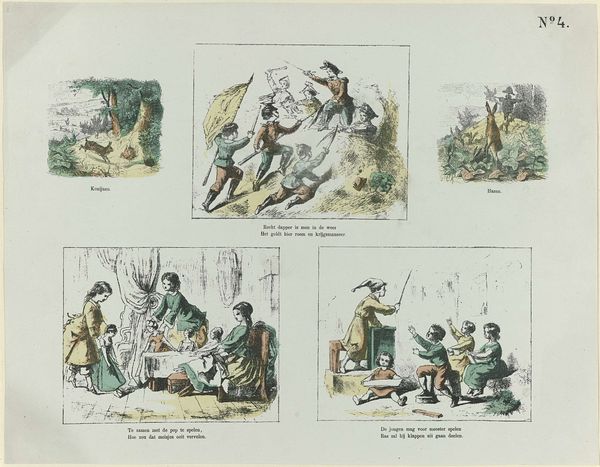

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

folk-art

#

symbolism

Dimensions: height 366 mm, width 267 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

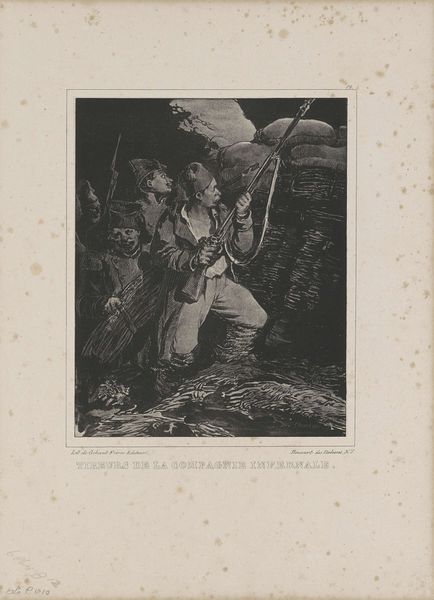

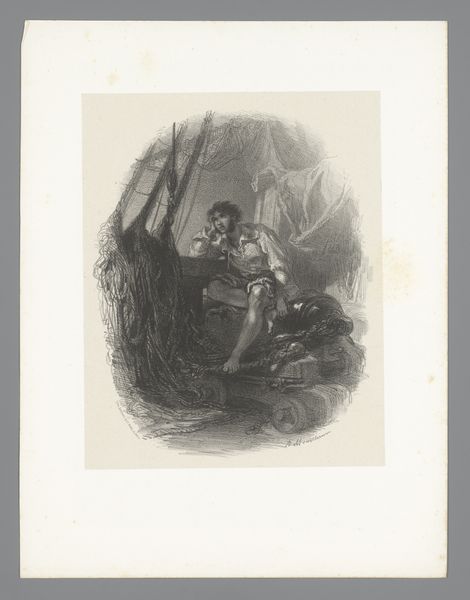

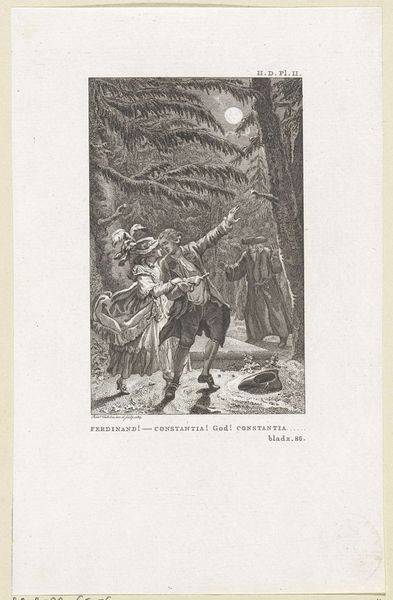

Curator: This compelling print, dating from around 1876 to 1890, is titled "De dood en de houthakker" or "Death and the Woodcutter," referencing a fable by Lafontaine. The print medium allowed for widespread distribution and reflects the common person's struggle in confrontation with mortality. What strikes you first about this piece? Editor: The overwhelming feeling is one of weary resignation. The aging woodcutter, burdened by years of hard labor, is now met with Death herself. I am curious as to what social or political commentary lies within the imagery here. Curator: Precisely! Consider the context. This print engages with powerful societal issues. It portrays a weary working man meeting Death in the forest. Prints like these had their socio-political impacts since it made it reproducible on newsprint media of that era and this form democratizes both art production and distribution while making visual commentary widely accessible to a populace that had little free time to ponder it. The image thus touches upon the working class experiences. Editor: Absolutely. And the personification of death is crucial, isn't it? She's not a terrifying monster but a gaunt figure, almost weary herself. It speaks to how inescapable social inequality and limited access to social safety nets like proper food and sanitation leads many to feel abandoned even if they seek spiritual or even material redress with organized religion as has always been the case. Death provides some measure of refuge, ironically. Curator: Note, too, the lines, the detail rendered, to give the shroud and scythe and skin all such realistic tactility for an audience that toiled so intensely; such attention must surely validate their suffering! The quality of the lines—thick here and fine there to describe mass and texture with a limited pallet, and a theme—to show to so many the plight and weariness to inspire change. It would appeal in that time to a classist sense of helping 'the least' of one's brethren as easily as now inspire unionisation and fair governance, it makes the viewer reconsider what labor and living, being alive, demands from a moral and material point of view. Editor: It makes me reflect on the exploitative aspects of labor then and even now. The image reminds us that systems favoring profit over people inevitably lead to situations where individuals are worked to death, both literally and figuratively, particularly given how the forest landscape can also symbolise the dangers inherent in labour itself as it consumes the person from the bottom up, from axe to wood dust to a withering death, if you will. Curator: The material impact—and accessibility—of print, the focus on labor and social hierarchies makes this not just a striking image but also a testament to print’s role in fostering awareness about inequitable material outcomes from imbalanced power dynamics. Editor: Indeed. By prompting this intersectional consideration through symbolic and material readings of the image, the piece reveals critical points in labour history still relevant in social movements today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.