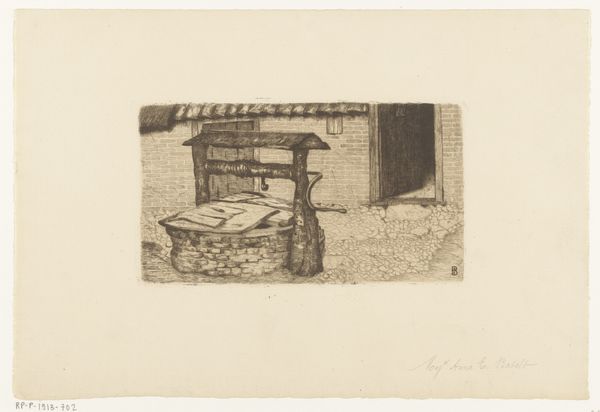

drawing, print, etching

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

pencil work

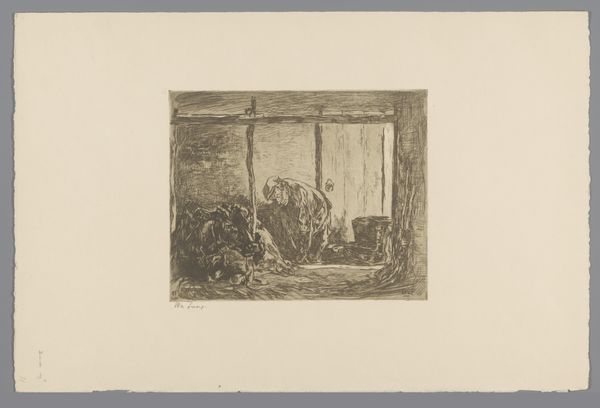

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The delicacy of this etching, "Konijnenhok," or "Rabbit Hutch," really strikes me. Wally Moes likely created this sensitive depiction between 1866 and 1918. It looks like she employed both pencil and etching techniques to arrive at the final print. Editor: My immediate impression is one of rustic charm. There's a certain stillness captured; it feels like a fleeting moment observed in the Dutch countryside. Curator: Definitely. Moes was interested in the pastoral and her style reflects her engagement with the Hague School's emphasis on realism. I’m fascinated by how the hutch becomes almost like a miniature cottage, a safe haven. What do you make of the cage-like netting at the window? Editor: Symbolically, it’s potent. It speaks to enclosure, captivity, perhaps even the tension between domesticity and freedom. Remember, during this period, anxieties about industrialization were prevalent, prompting a return to simpler, rural scenes in art and literature. Does Moes reinforce these sentiments or challenge them? Curator: She does something more subtle, I think. The "rabbit hutch" becomes an everyman’s dwelling. She emphasizes line, detail, and humble architecture, turning it into a narrative of simple living. Editor: I agree; the unassuming subject is precisely the point. In a society rapidly transforming, depicting everyday scenes becomes a form of cultural preservation. We must acknowledge, though, that the lives of these animals remained utilitarian. The rabbits, however sweetly rendered through artistic license, were destined for the table. Curator: Indeed. Yet there's also a tenderness in the way Moes delineates the form. It isn't just documentation; there is a visible affection for the quietness of rural life that infuses every stroke. Even in such mundane objects. It echoes that psychological weight imbued into animal representation through symbols across various eras. Editor: Perhaps Wally Moes hoped for viewers to acknowledge the reality, to acknowledge that smallness, fragility, even fleeting beauty—were all worthy subjects within shifting cultural paradigms. Curator: Ultimately, I am left pondering not only what is visible but the silent dialogue within, regarding societal values—the artist initiates and perpetuates with each finely rendered line. Editor: For me, this print underscores how ordinary, transient imagery in art can illuminate grander socio-historical dialogues of place and time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.