Dimensions: 210.8 x 153.5 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

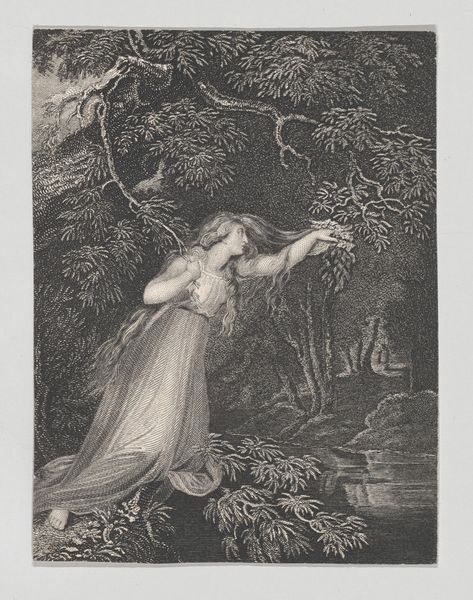

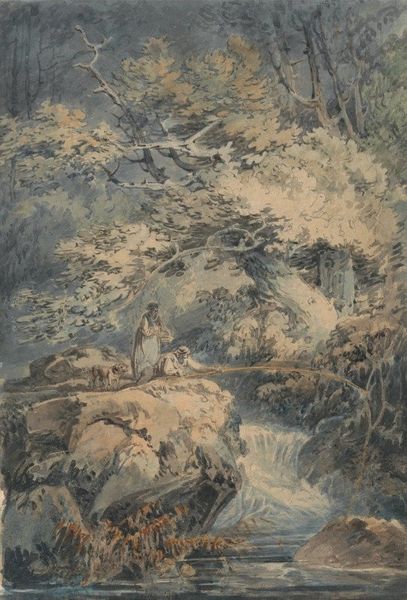

Curator: Welcome. Here at the Städel Museum, we have Victor Müller’s “Ophelia” from around 1869. It’s quite a piece, working in oil paints with influences from Romanticism and the Pre-Raphaelites. What are your first impressions? Editor: There’s a melancholic beauty about it. The scene is almost claustrophobic with the overgrown foliage, and this pale figure leaning against the tree—she seems trapped between worlds, doesn’t she? Curator: That sense of confinement reflects the social constraints placed upon women during the 19th century, a theme the Pre-Raphaelites frequently engaged with. Shakespeare’s Ophelia, driven to madness and death, became a potent symbol of female vulnerability and societal oppression. Editor: Absolutely, but Müller doesn't just re-present the tragic ending. There's a sensuality here that is troubling— the way she's posed, almost inviting despite the inherent sadness. Is it critique, or is it perpetuation? Curator: It's a complex negotiation. The painting draws heavily from the aesthetic and artistic tenets of the time. The setting is rendered with minute attention to botanical detail, reminiscent of realism and naturalism. Consider how the artwork places her, but the question persists: is it homage or exploitation of a woman’s sorrow and its spectacle? Editor: That's exactly the point, isn't it? The Romantic idealization of female suffering co-exists with a very real, very visceral portrayal of a woman's experience. We’re forced to confront our gaze. It’s disturbing. Curator: I agree. This piece offers a valuable glimpse into how artists and institutions reflected, or perhaps failed to reflect, societal anxieties and changing perspectives on female representation. Editor: It pushes us to constantly question and engage critically with art from the past, particularly in our efforts toward the kind of work still needed in the future. Curator: Indeed. Thank you for those insights. Editor: Thank you.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

Commission Art: in 1868 Victor Müller signed a contract with the art publisher Bruckmann in Munich, which obliged him to contribute to a Shakespeare cycle. The paintings were to be sold and the reproductions offered for sale in a high edition at the same time. It was obvious that the artist had to meet the expectations of the conservative buyers. “This all would be a great shredding of feeling. Melancholy, elegiac, blasé, unhappy, in short: quite curious,” is how Müller ranted about his work. This was not the place for radical pictorial concepts.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.