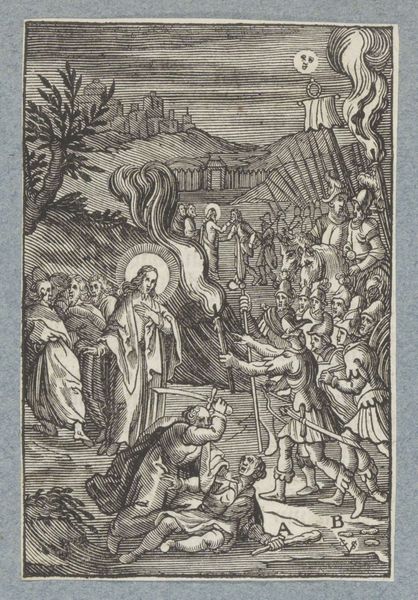

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 56 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

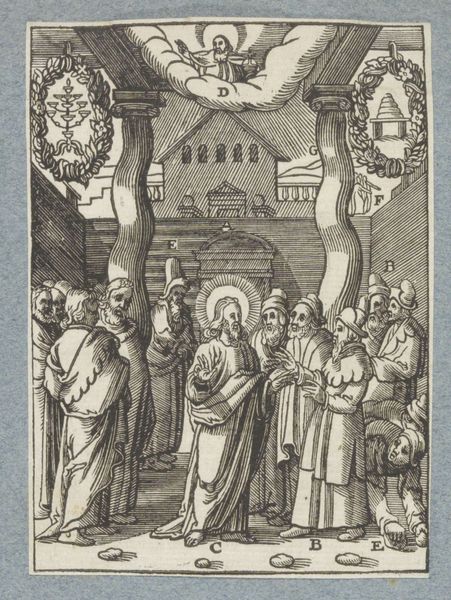

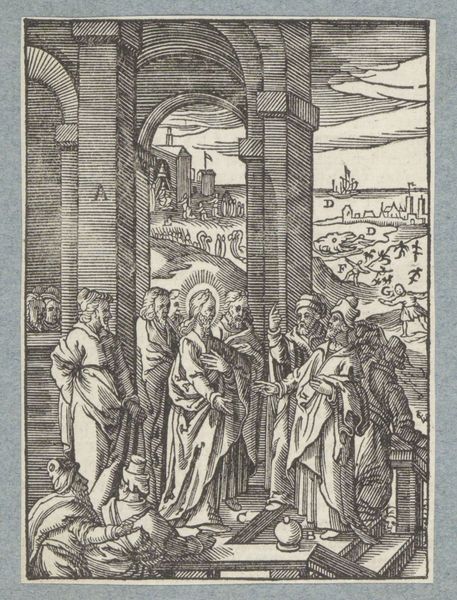

Curator: This is Christoffel van Sichem II's "Entry of Christ into Jerusalem," an engraving likely made between 1648 and 1657. Editor: My initial thought is how incredibly stark it is! The dense, almost frantic lines give it a real urgency. It’s visually very immediate. Curator: The use of line is paramount. Sichem skillfully employs hatching and cross-hatching to create form and shadow, but also to express an emotional fervor. Note how the faces are rendered, each with a distinctive expression that plays into the narrative of Christ’s arrival. Editor: And look at how that technique translates into material terms. Engraving demands incredible precision and labor. Think about the physical act of carving those lines into a metal plate, the controlled force required. The final print is a product of intense, focused work. Was it for a broad audience? Curator: Likely, yes. Prints such as this one were widely disseminated, offering a visual narrative to a broad public, reinforcing cultural memory. Consider, for example, the halo—an immediately recognizable symbol of holiness, instantly communicating Christ's divine status to viewers familiar with Christian iconography. Editor: Exactly, and the symbolic power depends on a level of shared cultural understanding that may not exist in the same way today. But even divorced from that direct context, the skill in manipulating the material – that intense black and white contrast achieved through laborious carving— that remains undeniably impressive and affecting. Curator: Absolutely. This print offers a lens into the visual language and belief systems of the 17th century, how it translated into very familiar symbols and archetypes, while using skillful techniques to engage the emotions and prompt introspection for anyone. Editor: And for me, it shows us the tangible act, the physicality, through which an idea can enter our world as a printed image: raw materials transformed by human labour. Curator: It invites you to explore, whether in its cultural context or its craftsmanship, and it leaves a powerful afterimage, doesn't it? Editor: Precisely, there's an echo of process inherent to it that speaks volumes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.