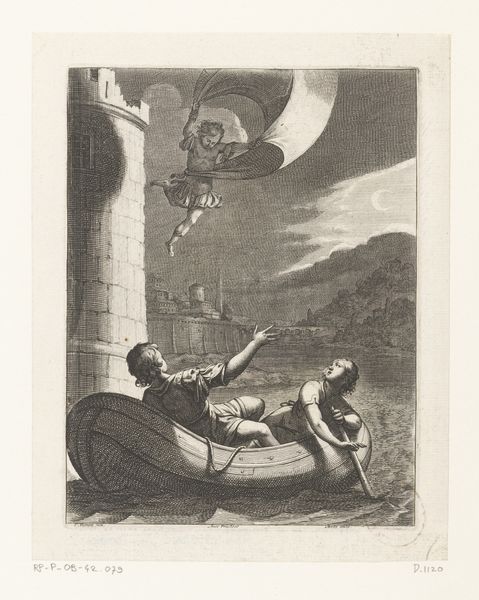

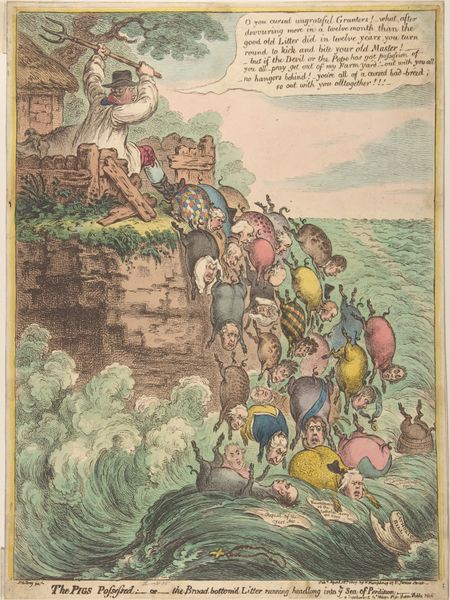

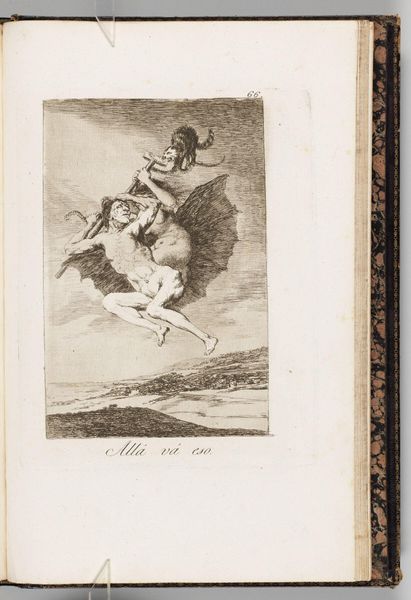

drawing, print, etching

#

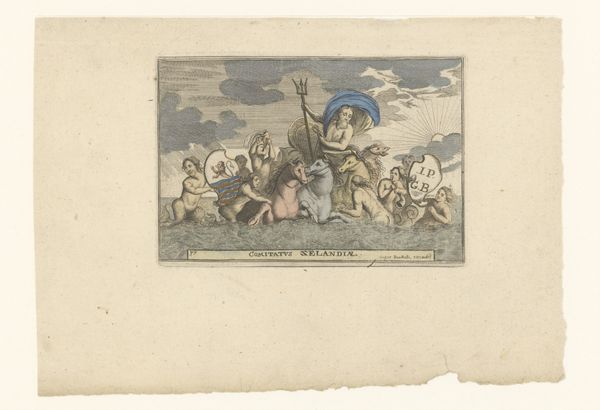

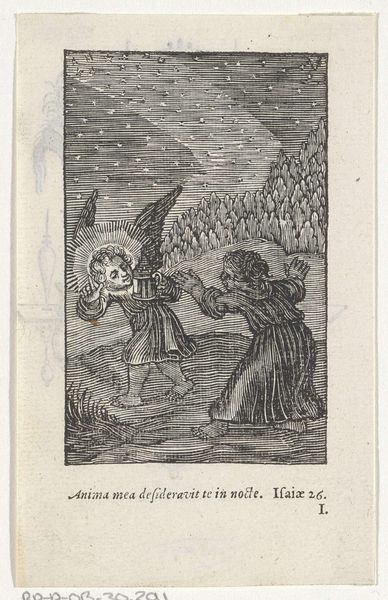

drawing

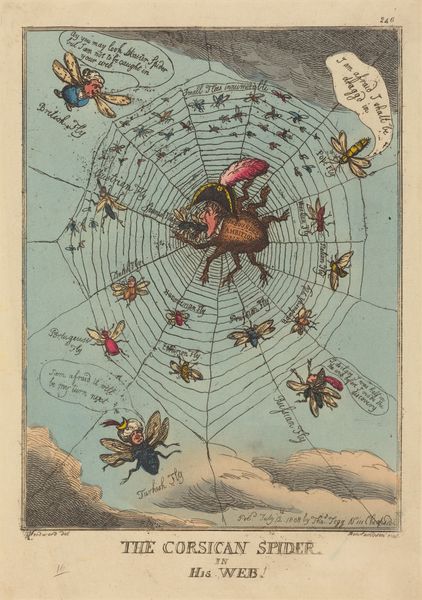

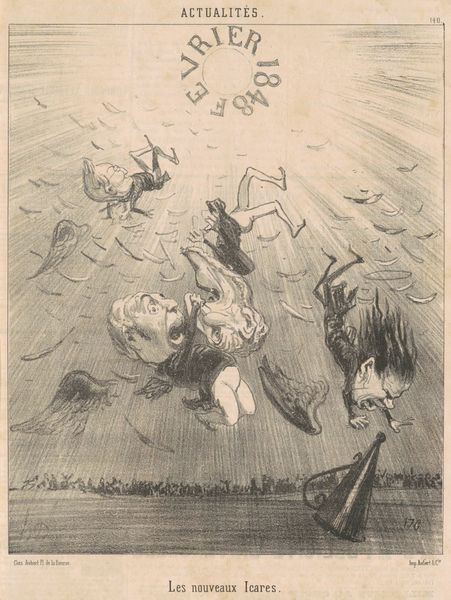

# print

#

etching

#

caricature

#

romanticism

#

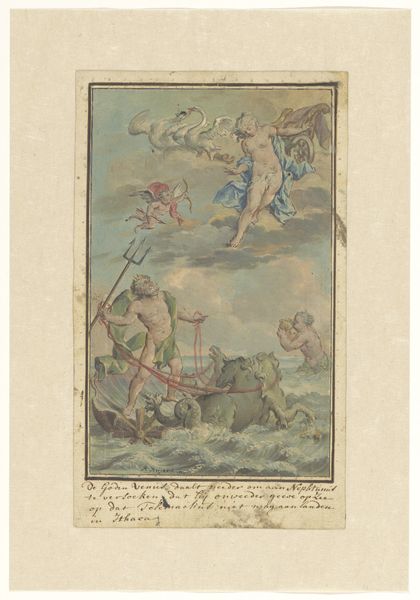

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Plate: 13 3/4 × 9 3/4 in. (35 × 24.8 cm) Sheet: 15 9/16 × 10 11/16 in. (39.5 × 27.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have "The Man in the Moon! or Consular Observations," an etching by Isaac Cruikshank, dating back to 1803. The tone feels really satirical; there’s this outlandish figure of a man superimposed onto the moon! What’s your take on this? Curator: The satirical edge is precisely where its power lies. Think about the context: 1803, the Napoleonic Wars. Cruikshank uses caricature here as a tool to critique power. It's not just about the visual humor; it’s about dismantling the perceived invincibility of figures like Napoleon through ridicule. What does it mean to put him "in the moon?" Editor: I guess it diminishes him. Makes him seem almost childish, like he's building sandcastles rather than commanding armies. Curator: Exactly. And look at the etching itself, a readily available medium. This wasn't meant for a gallery; it was meant for mass consumption. It suggests an appeal to a wider audience, stoking patriotic fervor and anti-French sentiment. How does the depiction of the British coastline in the foreground contribute? Editor: Well, you have the crowd, probably representing the British people, and then all of these ships on the water. They appear ready to resist any French advancement. Curator: Precisely. It’s a calculated juxtaposition: the inflated ego of Napoleon versus the steadfast, unified resistance of Britain. What does the handwritten text contribute to your understanding of the artist's goal here? Editor: It seems to mock Napoleon's broken English, which really pushes the satirical, almost xenophobic, reading. Curator: The caricatured figure, the exaggerated language... Cruikshank’s piece is not just a drawing; it’s a carefully constructed argument, leveraging stereotypes and fears to solidify a particular national identity in opposition to a perceived enemy. I wonder about the reception of images like this? Editor: It definitely highlights the power of art as propaganda during times of conflict. Curator: Absolutely, and understanding that power – both then and now – is crucial for us to become more media literate and active viewers of political art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.