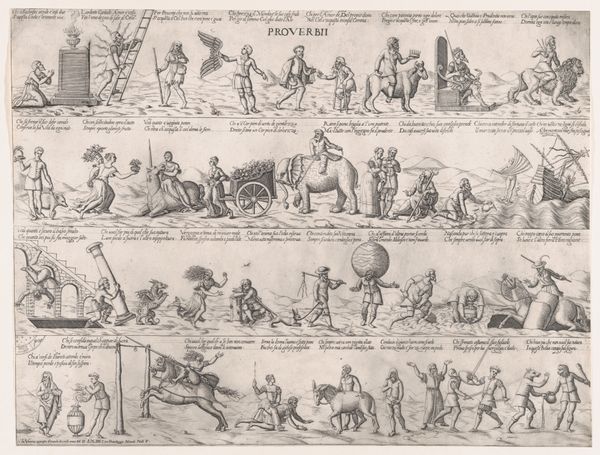

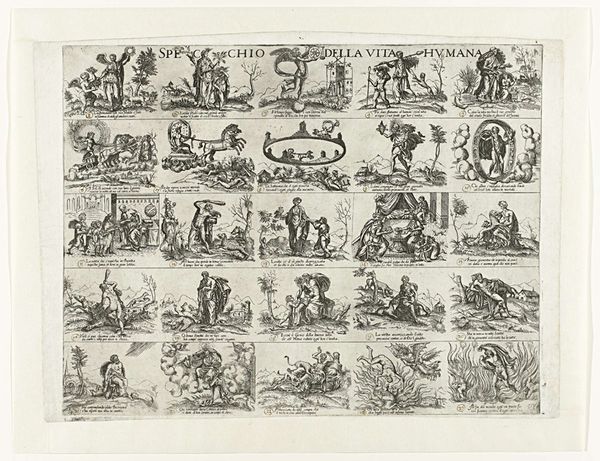

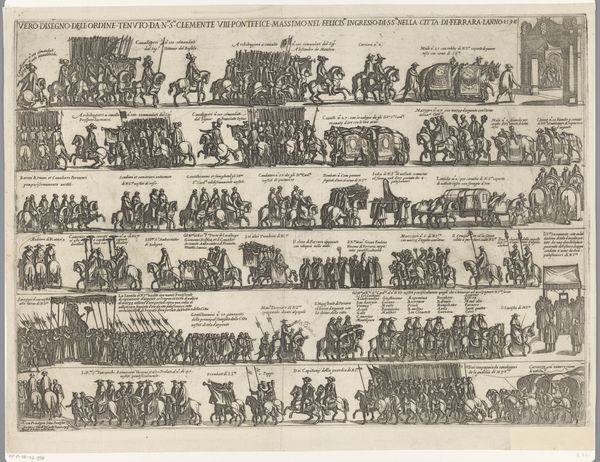

Blad met verbeeldingen van tweeëndertig spreekwoorden c. 1560 - 1590

0:00

0:00

adriaenihuybrechts

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

comic strip sketch

#

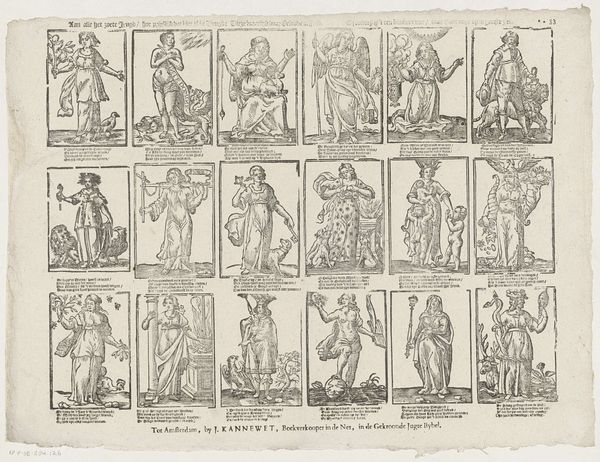

allegory

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

mannerism

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 357 mm, width 465 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

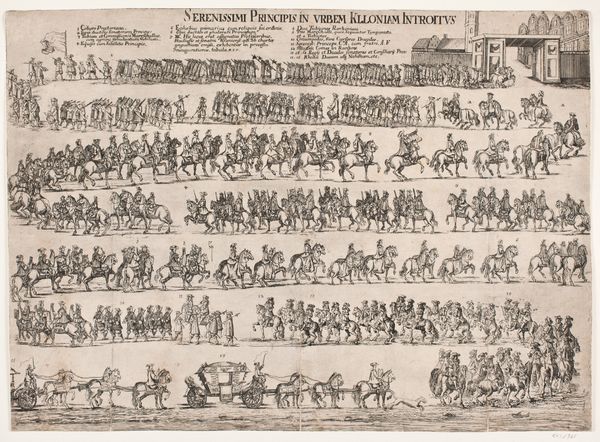

Editor: This is "Blad met verbeeldingen van twee\u00ebndertig spreekwoorden," made around 1560-1590 by Adriaen Huybrechts. It’s an engraving, so it’s printmaking, housed in the Rijksmuseum. There's a lot to take in; the composition is incredibly dense with these tiny scenes. What do you see when you look at it? Curator: The overall structure is fascinating. Huybrechts has compartmentalized thirty-two distinct visual units onto a single plane, challenging the eye to decipher each vignette individually before considering their relationship as a whole. Notice how the linework, although consistent, varies in density to define form and spatial relationships within each frame. How does this ordered chaos speak to you? Editor: I'm struck by the tension between order and chaos. It feels intentional. Each proverb has its own space, but they're all crammed together. Curator: Precisely. It presents a study in contrasts. Consider the distribution of light and dark; areas of deep etching create shadows, giving volume, whilst other regions remain open, airy. Does this play with light, influence your reading of individual scenes, and perhaps, the entire composition? Editor: I see what you mean about the shadows and highlights. It guides my eye through the print, highlighting some proverbs while others remain subtle. How might the specific choices he made with line and form help us interpret his message, beyond the proverbs themselves? Curator: We should contemplate how the use of symmetry, asymmetry, and repetition function on this page of engravings, alongside the visual rhythm—horizontal bands. Semiotically speaking, does the repetition of figures, their gestures, and expressions help us understand these proverbs better? Does this contribute to our reading of the entire work, considered not only as the addition of thirty-two elements, but a unified composition? Editor: I'm beginning to see how it all connects. The layout itself, the contrasts, contributes to the overall meaning. Curator: Indeed. Form, structure, composition, they're not merely aesthetic choices. In works like this, they actively shape our understanding and engage us in interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.