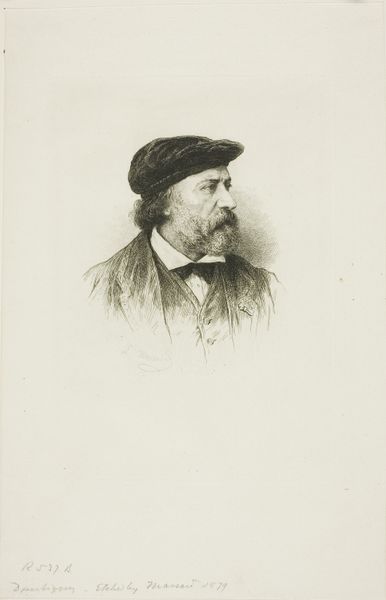

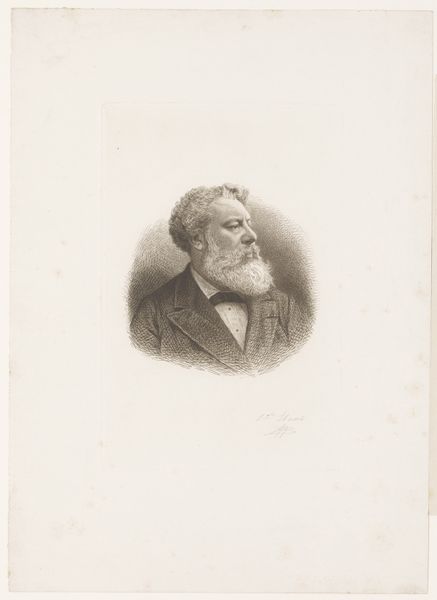

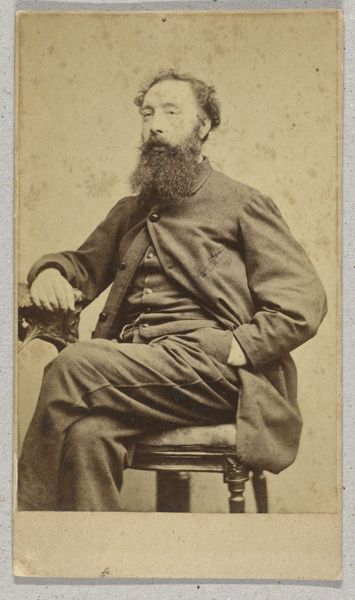

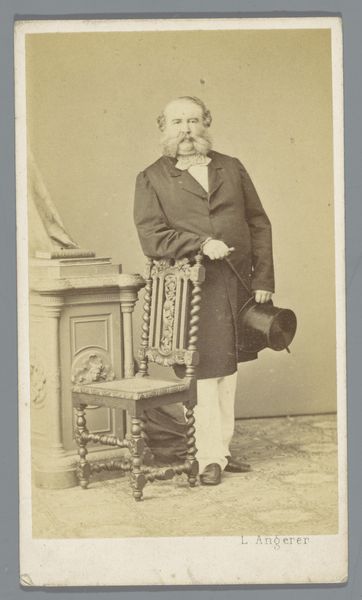

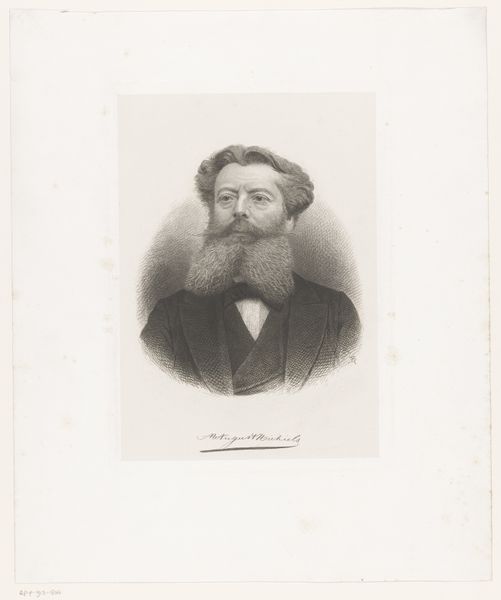

Portrait de Theophile Gautier d'apres Nadar c. 1857 - 1982

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

realism

Dimensions: 35.5 × 22 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

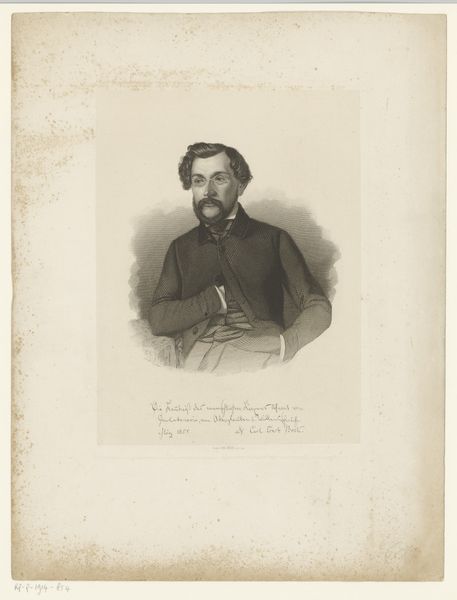

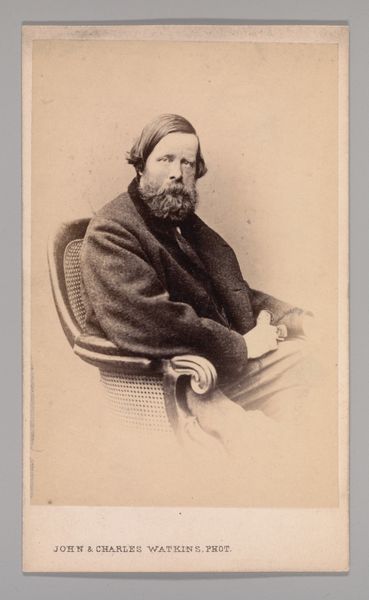

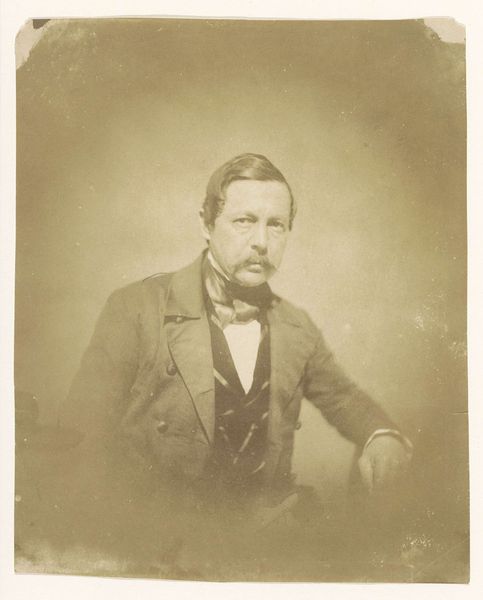

Curator: Welcome. We’re looking at a striking portrait of Théophile Gautier. Charles Nègre took this daguerreotype around 1857, and this print dates much later, circa 1857 to 1982. It's currently part of the Art Institute of Chicago's collection. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the somber, almost melancholic mood. The tones are subdued, and it feels very intimate, like we’re catching a private moment. Curator: Yes, daguerreotypes have that incredible level of detail and immediacy. In its historical context, we see the rise of photography and the shifting understanding of portraiture. Prior, portraits were only accessible to the elite. With photography we see the democratization of imagery, though certainly, some more than others! Editor: Exactly! It represents a moment when image production shifts, opening up all types of dialogues surrounding visibility and representation. Gautier himself, known for his writing, now becomes an object of the gaze. How do you see his identity, as a writer, shaped or reshaped through this portrait? Curator: Well, the dark clothing and head covering might indicate an artistic persona, or perhaps just practical clothing for a photographic sitting. Daguerreotypes demanded long exposure times, and immobility, which must have posed an interesting challenge for both artist and subject. We also should think about Nadar’s photography too. What ways was Nègre drawing from Nadar? What way was Nègre’s process, shaped by the existing imagery from figures like Nadar? Editor: It definitely brings up questions about performativity and authorship, who has the right to representation? Does that shift as well once these images go public and the subject potentially has no claim to the images circulation and dissemination? Curator: Absolutely. We should keep that context of circulation and audience in mind whenever viewing portraiture. Editor: It also prompts thoughts about who has the privilege to create these images and circulate them; Nègre himself being a somewhat overlooked figure in the historical narratives we see of early photographers, due to race. Curator: That is such an important question. Let's keep these important thoughts in mind as we continue the tour. Editor: Agreed. It adds layers of meaning and questions our preconceived notions about 19th-century portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.