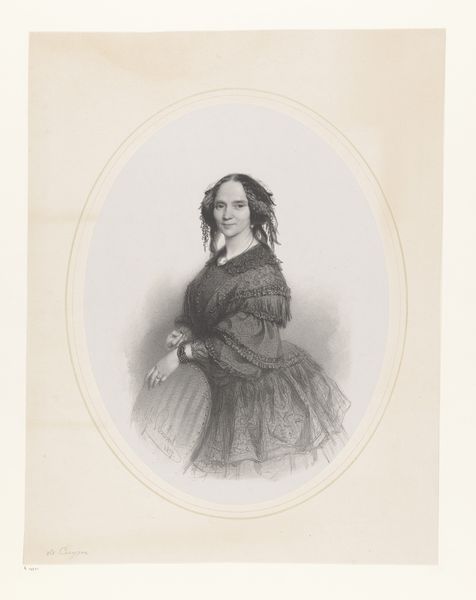

Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

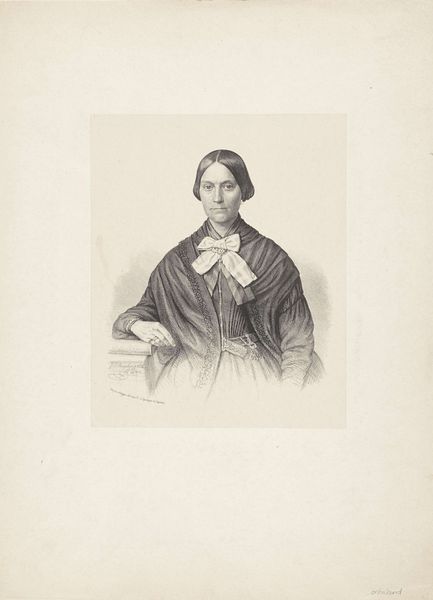

Curator: At first glance, this work has a somewhat somber air. It feels reserved, like a glimpse into a very private space. Editor: Indeed. Here we have "Portret van mevrouw Amersfoordt," or "Portrait of Mrs. Amersfoordt," rendered in the period between 1823 and 1900. The artist, Johann Wilhelm Kaiser, employed pencil and etching to create this striking image, now housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: The gray scale creates a sense of seriousness, almost historical distance. The woman’s attire, particularly the shawl and the brooch, suggest a certain status, or at least an intention to convey one. But her direct gaze also suggests some level of vulnerability. Editor: Absolutely. Consider the artistic trends during this time, too. The early 19th century was marked by a burgeoning middle class, keen to solidify their place in society. Portraiture became a tool, almost a form of visual branding. Notice, however, the absence of overtly opulent symbols. It’s a reserved display of status, aligning perhaps with the values of a burgeoning Dutch middle class. Curator: That resonates. It also makes me wonder about her personal story, beyond her social positioning. The inclusion of flowers and what appears to be a book gives me pause. Those may act as placeholders of domesticity and intelligence, standard iconographic flourishes. Editor: Precisely, these are symbolic gestures deeply ingrained within portraiture conventions. The flowers could indicate virtues, while the book signals literacy and engagement with the world of ideas. However, these symbols gain their resonance through a complex socio-cultural understanding. The public display of art allows access for these discussions. Curator: Seeing how we've considered the elements – technique, era, symbolism - allows to a better reflection about how societal narratives weave their way through these portraits. Editor: Very well put. Indeed, the portrait can then provide both a window into history, and mirror for our present, reflecting the enduring human desire to be seen, understood, and remembered.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.