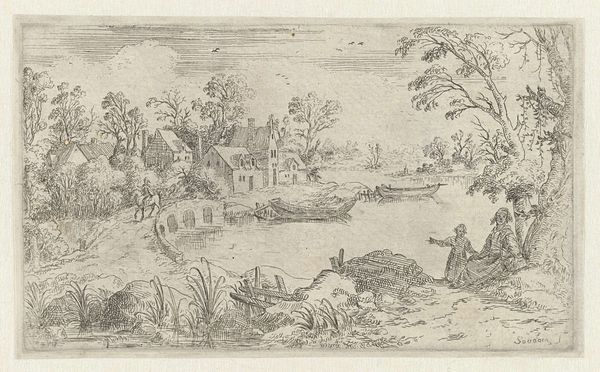

drawing, etching, pen

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

etching

#

landscape

#

river

#

line

#

pen

#

realism

Dimensions: height 141 mm, width 263 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Landscape with a Donkey and a Fisherman in the Foreground," a Dutch Golden Age etching that's attributed to Anna Maria de Koker, created sometime between 1640 and 1698. Editor: There’s a melancholy to this image. The fine lines, almost whisper-thin, create a sense of fragility. The detailed architecture on the left contrasts strangely with the vast, empty sky. Curator: De Koker's rendering, achieved with pen and etching techniques, captures the growing societal interest of the Dutch in landscapes. Remember, the Dutch Golden Age witnessed a rising merchant class eager to celebrate their connection to the land through art. This landscape reflects their worldview. Editor: It feels more profound than simple celebration. Notice how the lone fisherman and the donkey pulling a cart almost disappear into the overall scene? They represent humanity's smallness against nature's grand stage. It harkens back to memento mori traditions, reminding us of the transient nature of life. Curator: I agree there is a contrast between foreground and background. The artist may have deliberately framed humanity as an intricate component within an ecosystem which also needed careful regulation through waterworks and expanding political governance. Editor: Indeed. Water carries deep symbolic weight; cleansing, renewal, but also the subconscious and unknown depths. These little figures near the river suggest themes of navigation. Perhaps a psychological navigation too, mirroring one's life course. Curator: We also can't overlook how the detailed rendering of architecture becomes a focal point. Buildings symbolized stability and order – virtues which align with the evolving governance structures of the Dutch Republic during the period of this work. Editor: Still, that house gives me pause. Its details are beautiful, but its placement almost obstructs our full view into the landscape. The human desire to order nature comes at a cost; some part of nature will inevitably be obscured, even lost, during this pursuit. Curator: It really speaks to the dynamic relationship humans have in shaping and understanding our world. These 17th-century etchings weren't mere decorations; they represented profound societal ideals and, sometimes, their underlying contradictions. Editor: Yes, and how those ideals continue to shape our understanding of our place within the landscape, even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.