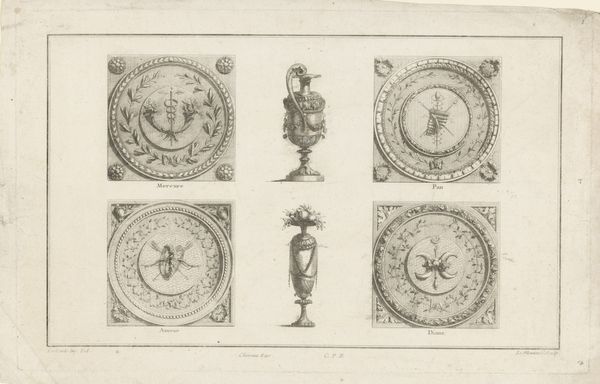

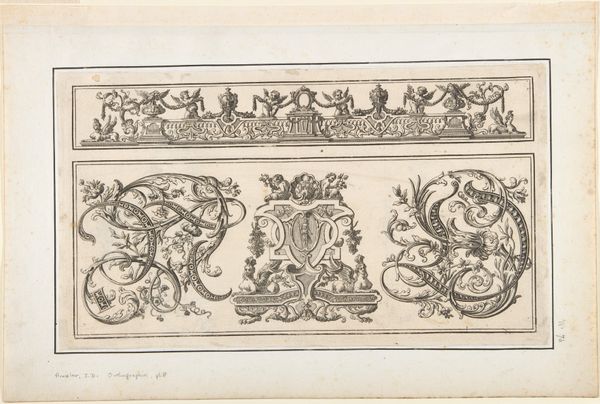

Six Designs for the Decoration of Rectangular Reliefs 1762 - 1844

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

ink

#

pencil

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: 4 5/16 x 5 7/8 in. (10.9 x 15 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

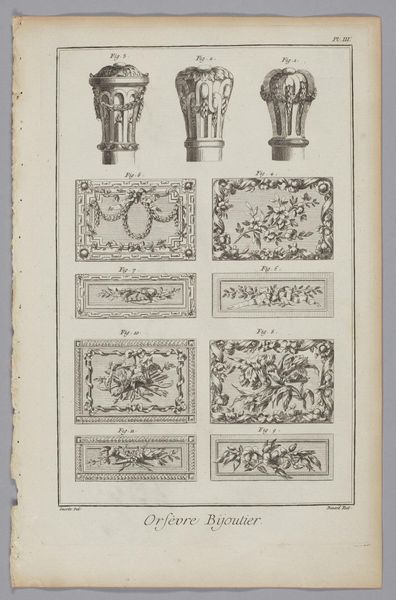

Curator: Alright, let's take a look at Giuseppe Bernardino Bison’s "Six Designs for the Decoration of Rectangular Reliefs," created sometime between 1762 and 1844. You'll find it here at the Met. It’s rendered in pencil and ink. Editor: Hmm, first impression: it feels like peering into a neoclassical confectionary. Elegant but maybe a bit dry, like those architectural ruins reproduced as cakes for a particularly fussy duke. Curator: "Dry" is one word. Consider the materiality: the precise strokes, the restrained use of ink wash, suggesting volume but denying us full, realized forms. It points to a period where design served power through the careful deployment of classical motifs, and that pencil on paper isn’t an accident, but rather, a very deliberate production choice reflecting an aesthetic focused on precision, reproduction, and functionality in the service of… who exactly? Editor: Someone who enjoyed things being "just so," I imagine. The motifs – urns, wreaths, abstract ornaments – are all incredibly stylish, but they are crying out for another medium. Look at the rendering style in the lower-right panel – a kind of decorative object vomiting scrolls, each scroll more pointless than the last! It begs to be blasted in terra cotta and adorn a Florentine palazzo or, I dunno, etched on a Wedgwood plate, something equally gaudy, but solid. Curator: But that's the beauty, isn't it? It *is* just a drawing. It resists that transformation into a solid object, highlighting the role of the artist as a creator of concepts, not just craft. We need to think of these relief designs as proposals in a world fueled by the aristocratic appetite, as opposed to finished products. The artist is, quite literally, rendering labor into possibility and submitting that labor to a market driven by a new type of class consumption. It reflects not just decorative refinement but social engineering, a way to visually solidify structures of wealth and influence. Editor: Engineering is correct, there is something a little bit calculated there for sure, it’s like someone thought deeply and decided this level of details had to be implemented at the time. Although it can seem overthought to the untrained eye. Curator: Right, these sketches reveal the gears of an emerging industrial machine that produces culture for profit, where a single sheet becomes a series of replicated luxury objects. Editor: So, we're both in agreement: fancy ideas generating revenue. A lot more insightful than I initially assumed by judging solely its aesthetic. Curator: Precisely. Seeing art, as labor materialized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.