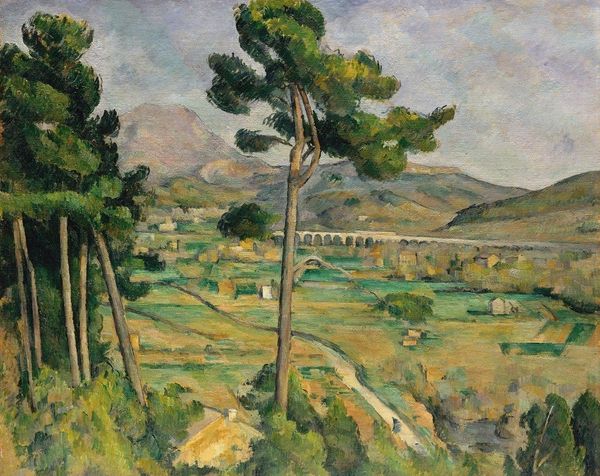

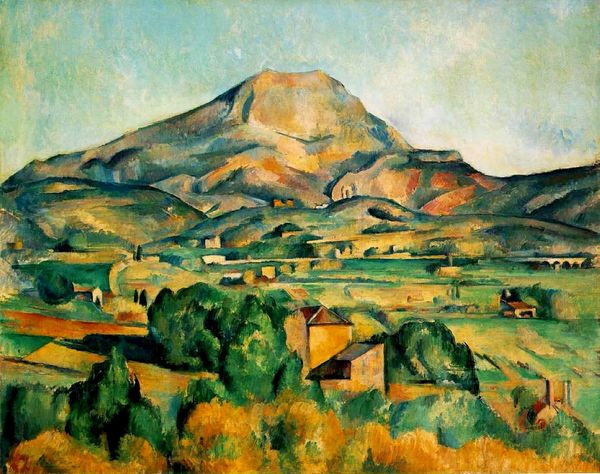

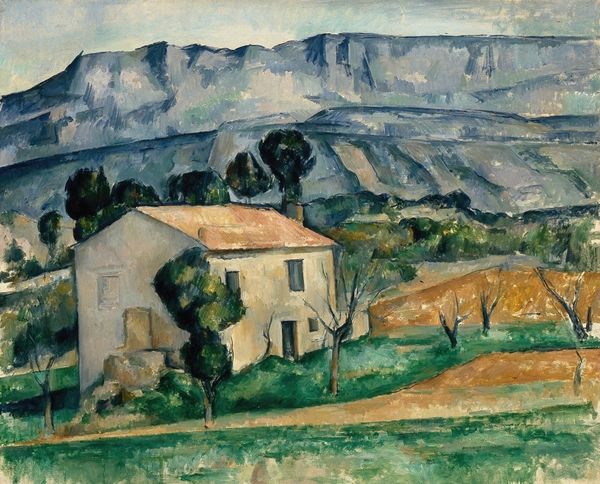

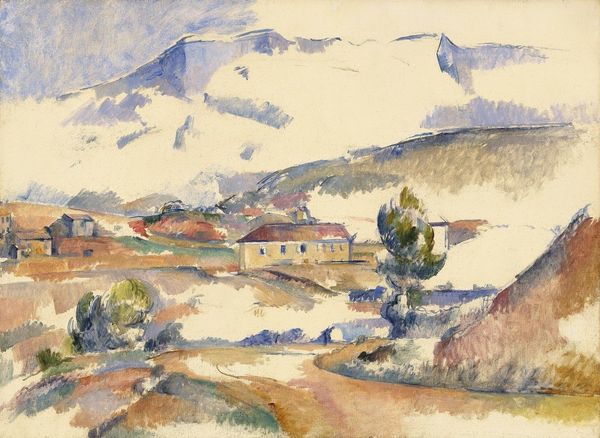

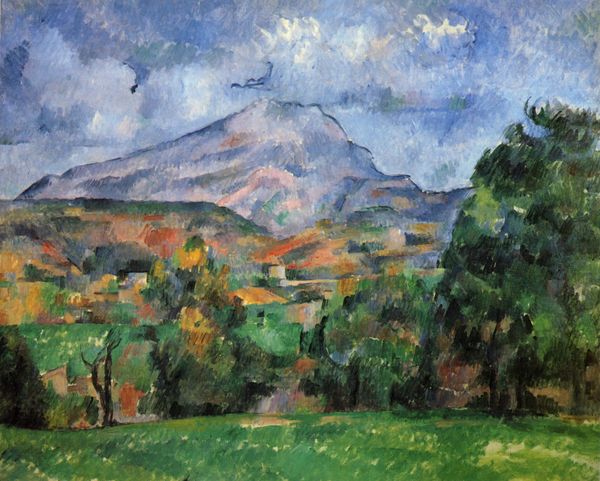

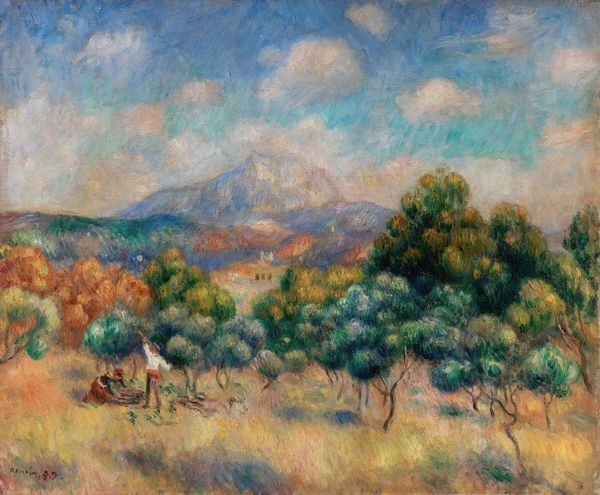

plein-air, oil-paint

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

oil painting

#

geometric

#

post-impressionism

#

modernism

Copyright: Public domain

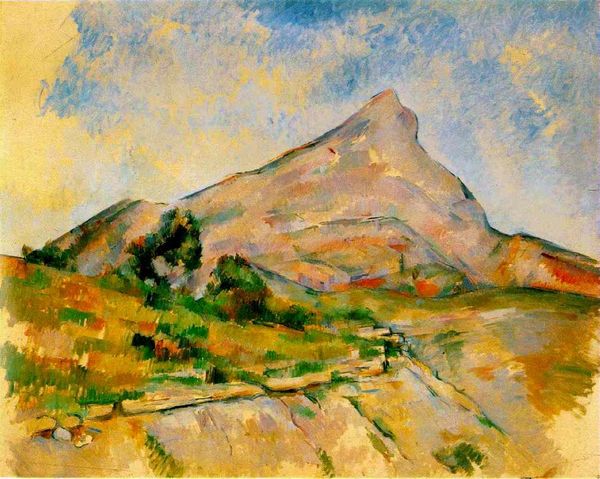

Curator: Well, hello there! What do you see first when you gaze upon Cézanne's "Mont Sainte-Victoire," painted around 1890? To me, it's less about what's depicted and more about *how* it's depicted. Editor: Honestly, a sense of groundedness. Like the mountain is just... there. Looming, yes, but also undeniably part of the landscape and our world. And yet there's a deep tension within what’s shown of "nature." Cézanne offers not some romantic backdrop but a solid entity interwoven with its environment. Curator: Groundedness, I like that! He did return to this motif countless times, almost obsessed. The mountain as anchor, as muse... you almost feel he was trying to unravel some secret hidden in its rocky form. He once said he wanted to "surprise nature." Which sounds cheeky but is almost subversive in that art world. Editor: Absolutely. This repetitive focus… I see it as him engaging with a very specific geographical site. Think about the historical context; this era was characterized by burgeoning industrialization which threatened the existing ecologies of landscape. In contrast to all that upheaval, Cézanne finds stability. There is no singular view presented; he creates layers within landscape. What exactly is the perspective point here? It's almost destabilizing, refusing a clear hierarchy. Curator: The destabilization... I think it adds to the intimacy. It's not about grand vistas but about *feeling* the space. And those blocks of color! Almost architectural in their arrangement. People often say it pioneered Cubism. Though perhaps he would chuckle at that interpretation. The joy wasn’t in geometric abstraction, but lived, sensory, *human* feeling. I want to run my hands along those colours like clods of earthy bliss. Editor: And that disruption of traditional perspective echoes a broader socio-political upheaval occurring simultaneously in the art and larger global spheres. If painting could abandon representational accuracy, why not other constructs? And who and what are often considered picturesque anyway? So much within Western canon excludes a huge number of bodies. To have the artist return to something ordinary and common becomes, paradoxically, radical. Curator: Beautiful. You make me think of that essay where Merleau-Ponty writes that, for Cézanne, art was "an interrogation of seeing." It was almost as if he painted not what he *saw* but the very *act* of seeing, struggling for this authentic encounter, for that fleeting moment. Anyway, whatever he hoped to see, he made it a little bit easier for the rest of us. Editor: Indeed. There's something incredibly egalitarian within how Cézanne frames landscape. We see its familiarity not from a fixed, untouchable distance, but from an intimacy interwoven in time and with nature, not detached, static artifice. Thank you for showing this other facet to the work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.