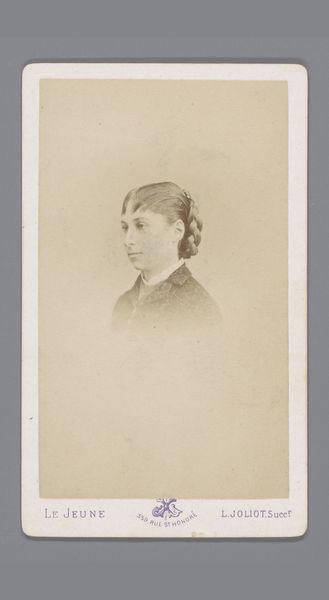

Bildnis einer Frau im Profil (Bildnis des Fräulein Irma Müller-Krämer) 1898

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Bildnis einer Frau im Profil," or "Portrait of a Woman in Profile," rendered in 1898 by Emma Heerdt. It's a red chalk drawing on paper, currently held at the Städel Museum. Editor: It strikes me immediately as quite delicate. The subtle shading of the red chalk gives a sense of warmth and intimacy, despite it being a profile, somewhat detached. Curator: Absolutely. Profiles in art often speak to status and power. However, the soft lines and medium used here, chalk and paper, lends a more human feel, a tenderness that moves away from idealized formality, wouldn’t you say? Editor: I do. Though a specific individual—likely one Fräulein Irma Müller-Krämer—is depicted, the treatment evokes broader conversations around femininity and societal expectations. There’s almost a hesitant quality in her expression. Curator: Her hair is styled, not unbound, and her garments presentable yet unflashy. It fits the symbolic order of the day where visual communication conformed to set ideas about womanhood in that era. There are even some neoclassical echoes. Editor: It also feels indicative of the romantic undertones seeping into late 19th-century academic art, even when portraying such a clear, respectable sitter. The choice to render it almost entirely in sanguine suggests passion held in check, or perhaps an awakening sensuality of the era. Curator: Red chalk naturally draws associations to blood, warmth, vitality—certainly all elements the romantics played with. To keep to classical and renaissance traditions for the formal elements while also suggesting at something beyond mere appearance speaks of the period’s social climate: adhering while subtly diverging from expectations. Editor: That slight almost suppressed smile adds another layer. What dreams or ambitions might have run beneath a poised and placid surface. What tensions and contradictions she was experiencing within herself during this period, at the turn of the century. Curator: Precisely! A subtle gesture in her portrait can open conversations on wider trends in identity and how these evolve, persist, and become embedded in the language of images over the years. Editor: Ultimately, such works prompt us to wonder not only who the sitter was, but how portraiture itself has shaped our understanding of people. Curator: A vital point to take away, especially since our engagement with such pieces keeps this dynamic, vital conversation current and always being reinterpreted!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.