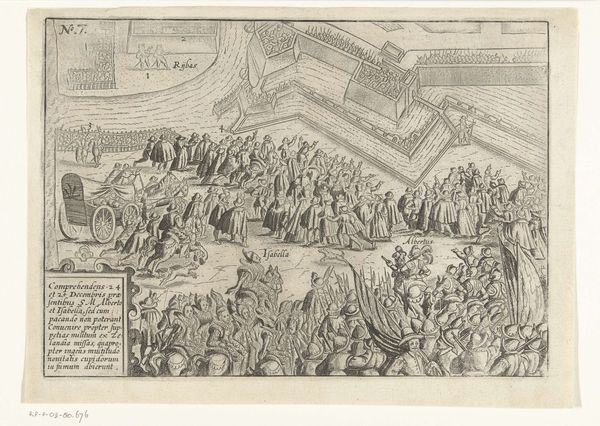

Dimensions: height 280 mm, width 402 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

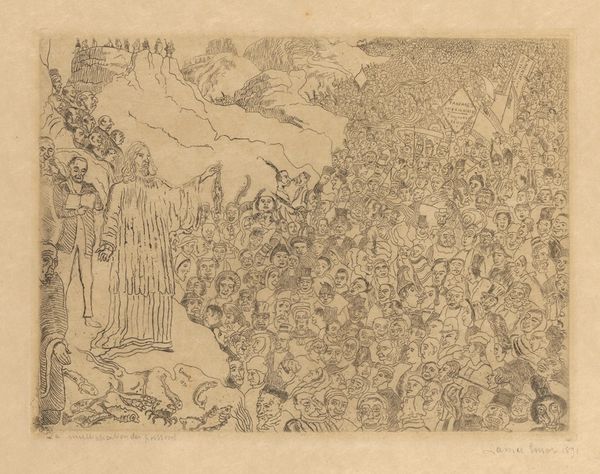

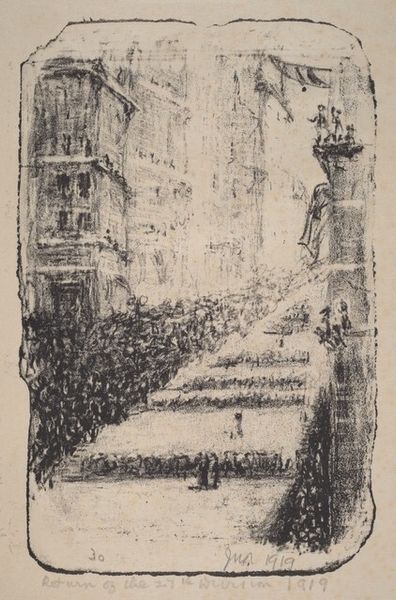

Editor: Here we have Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof’s "Toeschouwers op de tribunes van Circus Carré," a drawing made with pencil and charcoal, sometime between 1876 and 1924. It's really interesting how he captures the crowd – it feels almost like a single mass, yet you can still sense individual figures. What strikes you about this work? Curator: The material reality of this piece is compelling. Look at the labor involved: the repetitive strokes, the dense accumulation of charcoal. It speaks to the artist's process of observation and recording. Consider how the materiality contributes to our understanding of class and leisure. Circuses, at that time, became popular forms of mass entertainment for emerging middle classes, yet still catered for more affluent patrons in special seats or boxes. This sketch may illustrate varying conditions for viewership, literally inscribed by Dijsselhof in the use of certain strokes or stronger concentrations of graphite. Editor: So, it’s not just about what’s depicted, but about the work that went into depicting it, and how the materials and means reflect class dynamics. How does focusing on that change our perspective on the 'impressionistic' style, versus just looking at subject and aesthetics? Curator: Exactly. The so-called Impressionistic style, rather than being a simple rendering of optical sensation, becomes an active negotiation with industrial means of production, mass consumerism and shifting labor relations. Think of how the mass produced charcoal stick itself – readily available and affordable to an increasing demographic – impacts Dijsselhof’s artistic decisions. Editor: That's fascinating. I never thought about the materials themselves carrying so much social weight. So, by looking at the process and material, we learn as much, or perhaps more, about the circus goers than just studying their portraits. Curator: Precisely. By considering the materials, the methods, and the social context, we unlock deeper understandings that aren't necessarily visible on the surface. The drawing serves as a material record of a moment in cultural history. Editor: I see that shift in understanding now; it’s a really interesting approach to analyzing art!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.