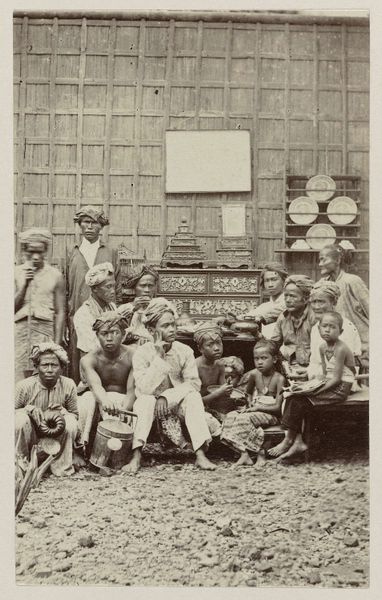

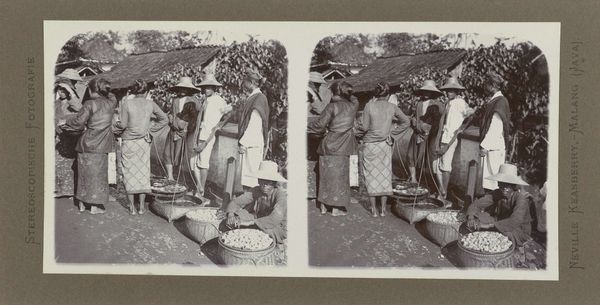

Arbeiders schudden rijst voor eigen consumptie op plantage Accaribo te Suriname 1916 - 1930

0:00

0:00

theodoorbrouwers

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 8 cm, width 5.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this gelatin-silver print by Theodoor Brouwers, taken sometime between 1916 and 1930, is called "Arbeiders schudden rijst voor eigen consumptie op plantage Accaribo te Suriname," which translates to "Workers Shaking Rice for Own Consumption on Accaribo Plantation in Suriname." It's striking how this image, while depicting labor, feels very staged and… almost anthropological in its approach. What do you see in this piece that I might be missing? Curator: You're right to pick up on that tension. Photographs like these, produced during the colonial period, are complex documents. Brouwers’ work, presented as a depiction of everyday life on a Suriname plantation, participates in a larger visual culture used to legitimize colonial power. The staging you noticed, while perhaps intended to showcase the process of rice preparation, also reinforces a particular power dynamic – the "native" subject presented for the observation and consumption of the colonizer. Consider how this image would circulate – in ethnographic publications, perhaps, or as postcards sent back home by Dutch officials. What kind of narrative would it construct? Editor: A narrative of exotic labor, I suppose, reinforcing the idea of a "productive" colony and the benevolence of the colonizer. It's troubling. Do you think Brouwers was intentionally creating propaganda? Curator: It's difficult to ascertain the artist's intentions. However, intention matters less than the work's reception and historical function. The image participates in the construction of a colonial gaze, regardless of Brouwers' personal beliefs. These visual representations often justified economic exploitation and the disruption of local cultures by portraying them as inherently different or “primitive." Editor: I see your point. It's less about the individual artist and more about the broader system in which the work operated. Now I’m wondering about the role the Rijksmuseum plays in displaying it. Curator: Exactly! The museum, too, becomes a site where these historical power dynamics are negotiated. Exhibiting the photograph alongside critical analyses and acknowledging the legacy of colonialism can challenge the original narrative and open space for a more nuanced understanding. Editor: This makes me think about the responsibility museums have in framing potentially problematic images. Thanks; this gave me a lot to consider! Curator: And it’s important for visitors to engage critically with these images and ask those hard questions. The past continues to shape the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.