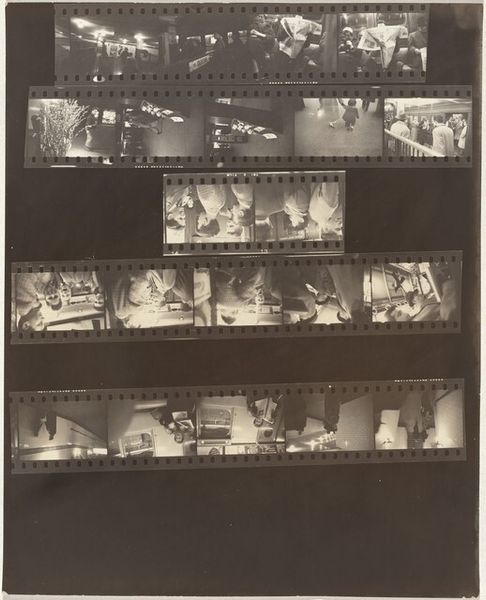

photography, gelatin-silver-print

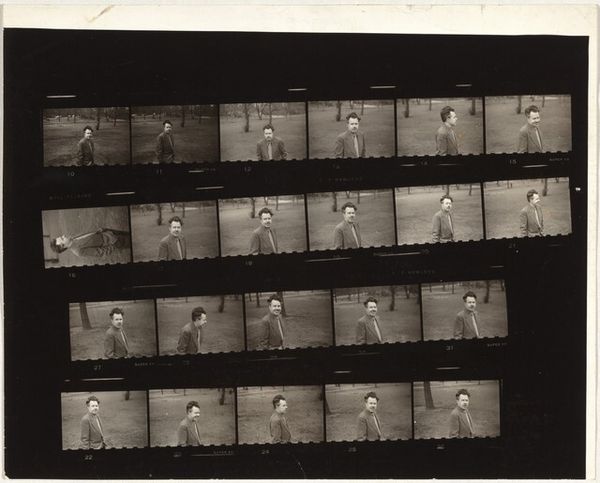

#

portrait

#

film photography

#

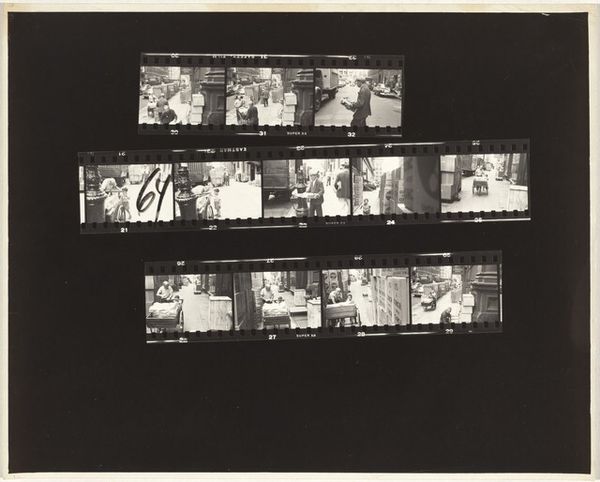

street-photography

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

film

#

realism

#

monochrome

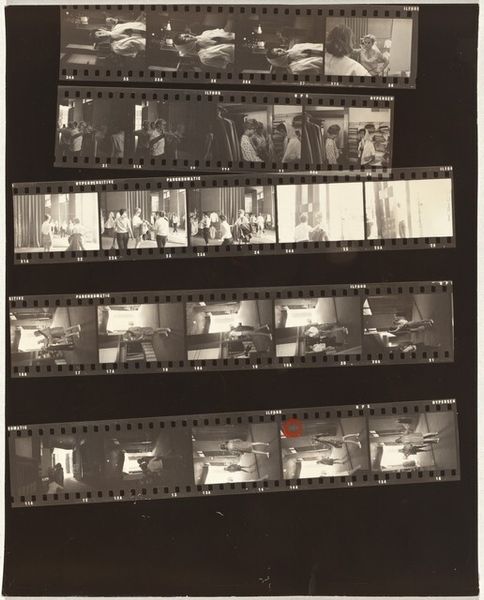

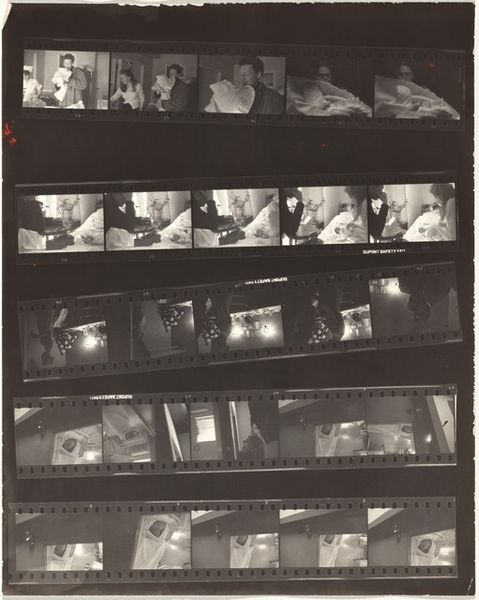

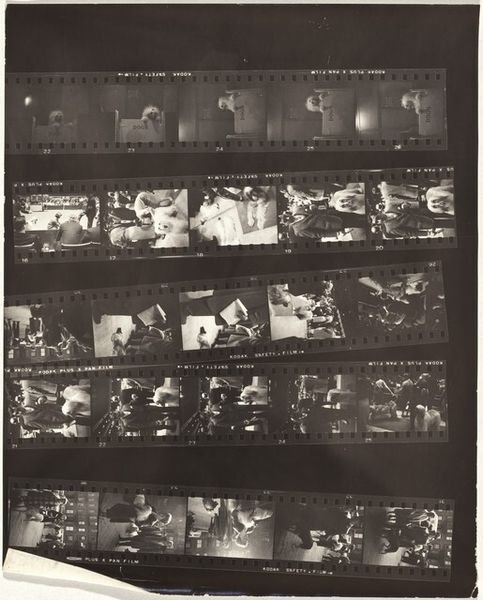

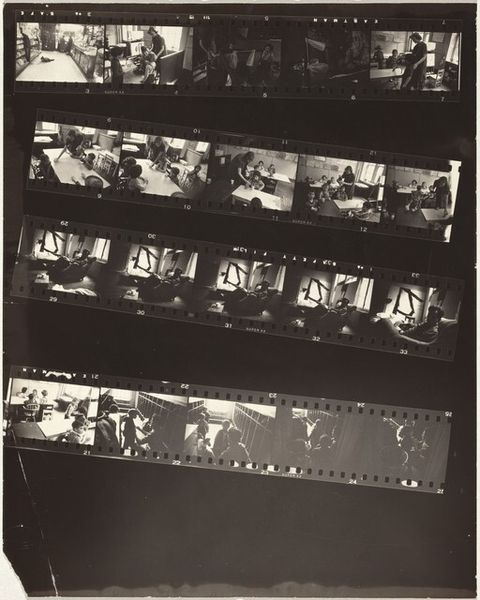

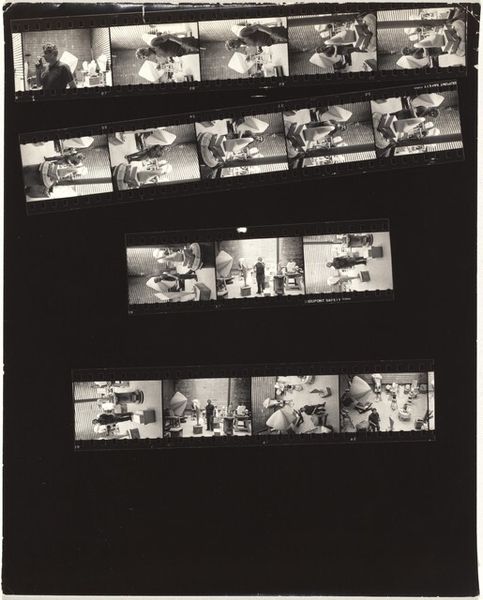

Dimensions: sheet: 20.3 x 25.2 cm (8 x 9 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

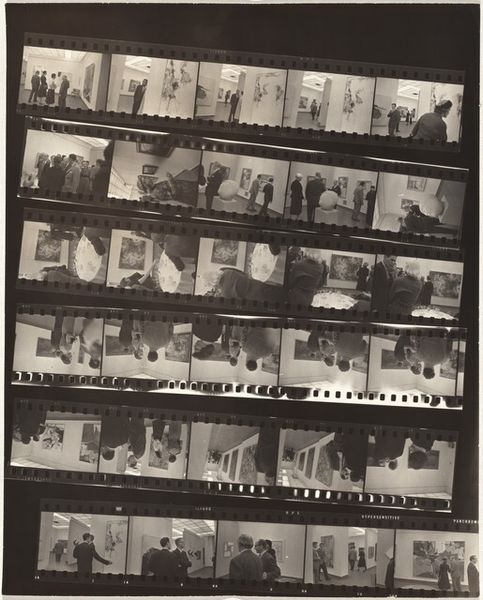

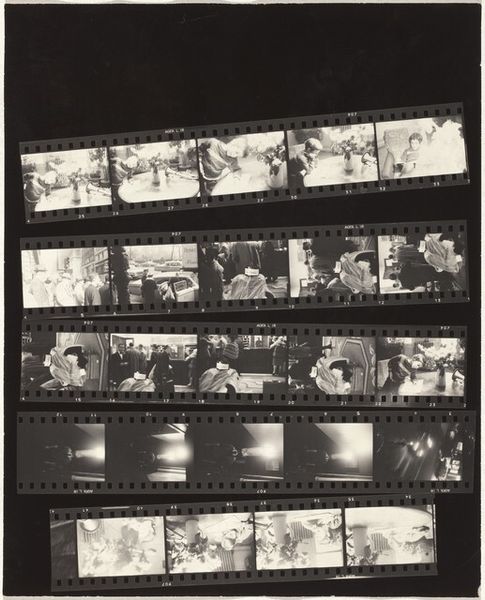

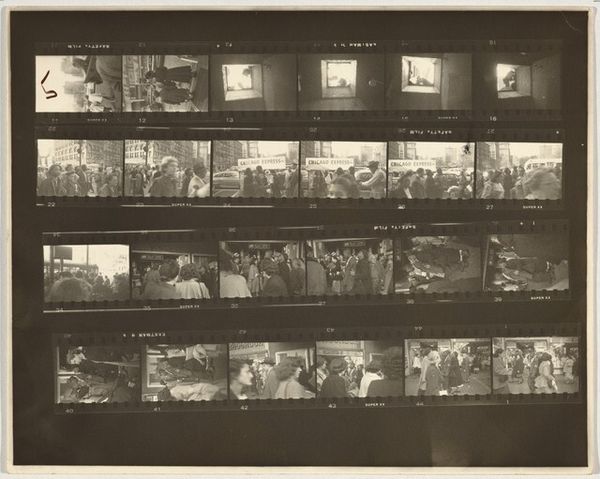

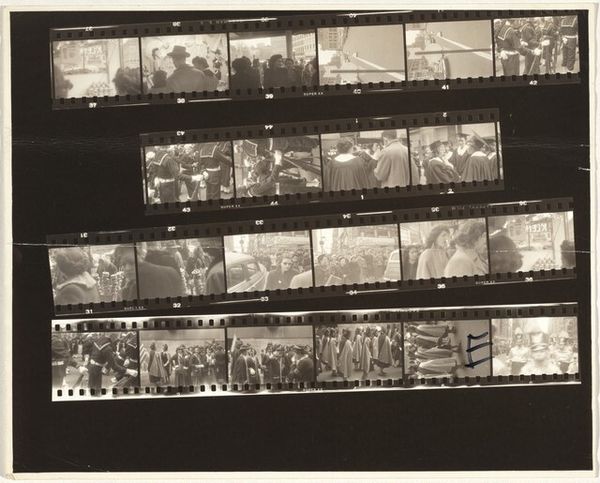

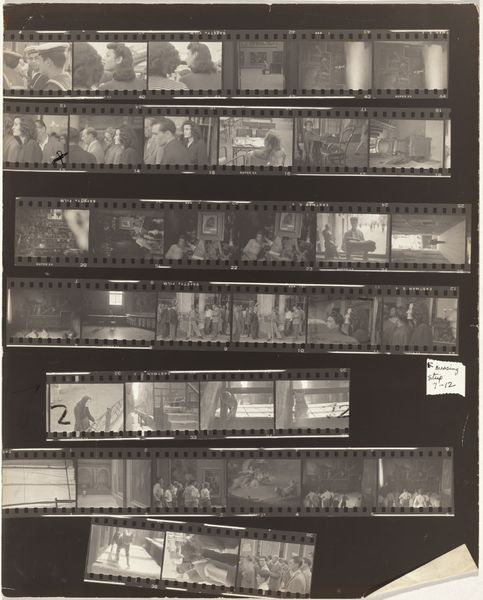

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the sheer ordinariness of this image, its raw depiction of family life. Editor: Yes, Robert Frank's "Family--New York City 20", a gelatin silver print from 1951, does have a powerfully unvarnished quality. The composition, a series of film strips laid out on a surface, highlights the mechanical nature of image production. What symbols or motifs jump out at you? Curator: Well, beyond the immediately recognizable figure of the family, what grabs my eye is that lampshade which appears on the second line of strips. Its repeated presence signifies domesticity. A warm, yet sometimes stifling atmosphere. It suggests routine, enclosure. It’s a common object, yet its recurring presence elevates it almost to the level of a domestic icon. Editor: Precisely, the repetition reinforces its symbolic importance. Think about it, Frank created this in New York, right in the heart of the burgeoning media landscape of the time. What do you make of it, placed in its historic context? Curator: Placing Frank's work into its era, it resists the saccharine portrayals of family then rampant in advertising and popular culture. It’s tempting to label this as documentary realism, but what interests me most is that such work pushed photography to be more deliberately, more recognizably subjective, a perspective beyond objective mirroring. Frank made a deliberate political act by emphasizing the intimate realities of his subjects. Editor: Indeed. Frank was keen to unmask certain dominant myths in America. Even the form itself is telling. By leaving the film strips visible, he isn’t just presenting a finished image, but revealing the process, the choices inherent in the making of meaning. He captures fragments of daily reality. Curator: He lets the audience see how constructed any photograph is, and maybe how easily narrative can then be produced from even such bare materials. I can see it now; the unpretentious snapshot becoming its own powerful sign. Editor: So, rather than simply seeing an ordinary image of a family, we are looking at a complex network of signs and social statements about what it means to be human in the middle of the 20th century. Curator: An image which resonates deeply for what it says both about familial identity and how meaning gets shaped.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.