#

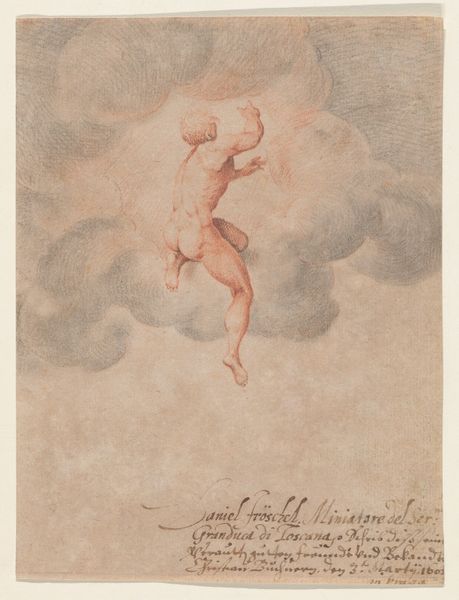

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

shading to add clarity

#

pencil sketch

#

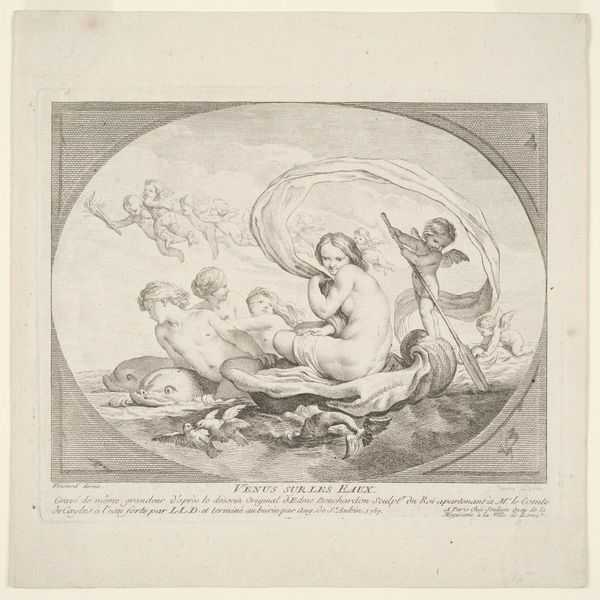

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink colored

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

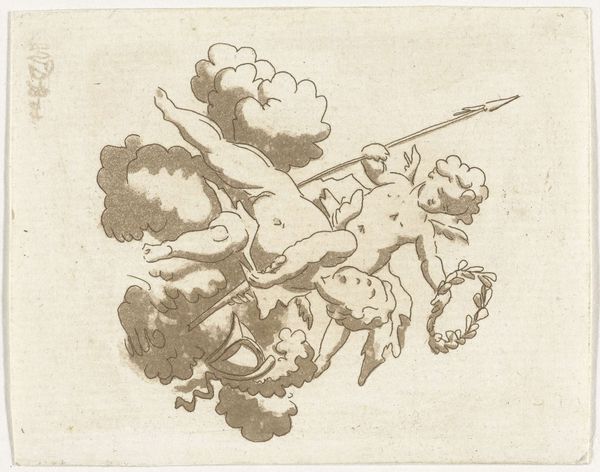

Dimensions: height 45 mm, width 71 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Putto met een ouroborus," dating from 1735 to 1800, by Giovanni Cattini. It seems to be a pen and ink sketch. I’m immediately drawn to the circular composition created by the ouroboros – a snake eating its own tail. It gives the piece a sense of cyclical time and infinity. What’s your interpretation? Curator: Well, the ouroboros is certainly a loaded symbol. Contextually, think about the burgeoning interest in alchemy and the occult during this period. It's not just a pretty symbol; it carries weighty connotations. Why would an artist like Cattini, working within the artistic institutions of his time, choose such a powerful, potentially subversive, image? Editor: Subversive? How so? Curator: In some ways, because the established Church held enormous social power, incorporating pagan or alchemical symbols could represent a subtle challenge to established norms. Do you notice how the putto, a figure strongly associated with Christian art and cherubs, almost *wears* the ouroboros like an emblem or halo? That combination could also reflect the social effort of incorporating classic, older symbols within Christianity's frame of reference. Editor: So, it's playing with accepted religious imagery by injecting other ideas? Curator: Precisely. Furthermore, the skill apparent in rendering suggests its purpose exceeded personal, idle musings in a sketchbook. Instead, it possibly hints at prints meant for larger circulation among people who might debate the nuances and cultural associations. Have you looked into print culture of the era? Editor: Not yet, but this definitely gives me a lot to consider. I'm now viewing this putto in a different context than I did just a moment ago. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. The social implications woven into art can significantly shift how we perceive a seemingly simple image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.