drawing, lithograph, print, paper, watercolor, ink, pencil, chalk

#

portrait

#

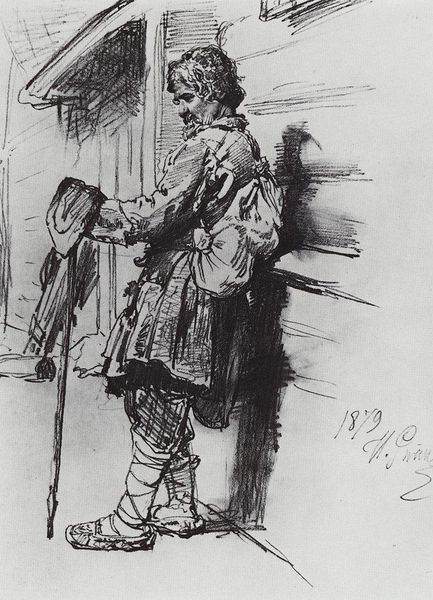

drawing

#

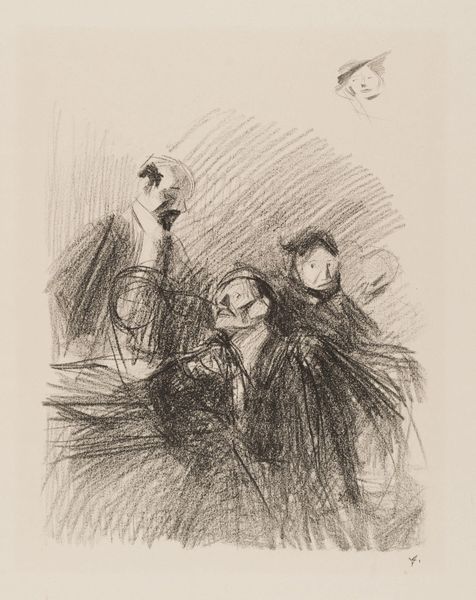

lithograph

# print

#

impressionism

#

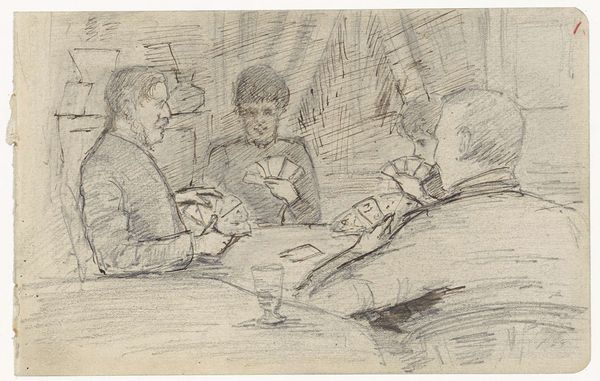

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

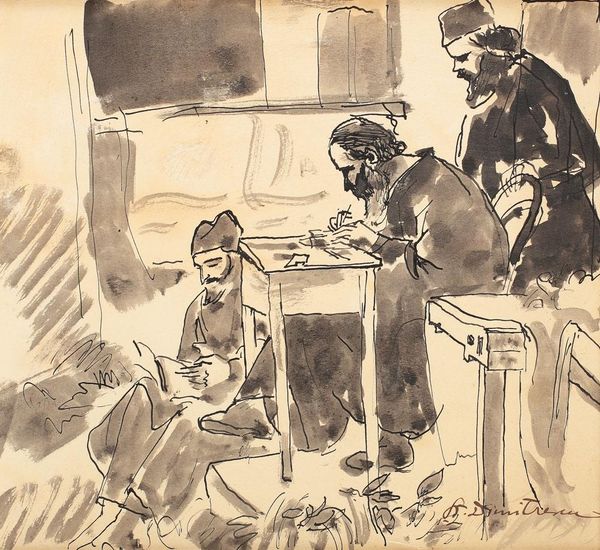

watercolor

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: 215 × 321 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

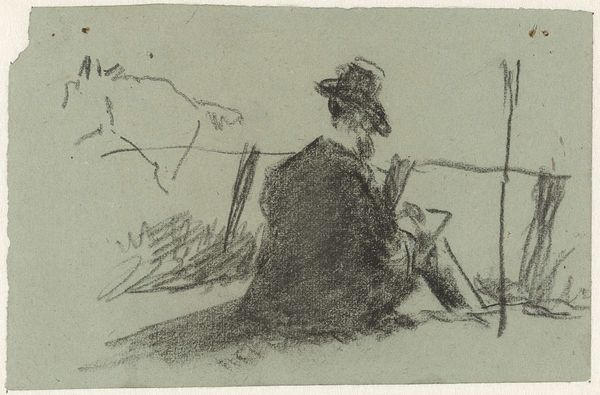

Editor: So, this is Honoré Daumier’s “Third Class Carriage” from 1864. It’s a print, a lithograph to be exact, in ink and chalk. There’s such a dense feeling in the image; it looks very somber. What's your read on this artwork? Curator: This image strikes me as a stark social commentary. Daumier doesn't simply depict people; he's presenting a portrait of marginalized society and their resilience, would you agree? Note the emphasis on those traveling in third class—those least privileged who are forced to crowd together. It brings into question issues of social justice. Editor: Yes, there is a stark difference between the carriages for different classes in the 1800s. It's amazing that Daumier puts faces to this forgotten part of society. What does their inclusion of everyday folk represent in terms of societal shifts happening during his time? Curator: Daumier actively challenged the norms by prioritizing the common person. In that respect, we have to view Daumier as both artist and documentarian. His use of lithography was critical for mass distribution; in essence he’s creating art that is easily and cheaply disseminated so he can reach a wide audience. It's not just about showing third-class passengers, it's about bringing their struggles to a bourgeois audience who probably never had to ride in those carriages. It's a deliberate act of disruption. Does it speak to how images can promote political activism even in our world today? Editor: Absolutely. Seeing this now, it definitely makes you think about who is missing from our own contemporary narratives. What are some things about lithography I should be looking at? Curator: Consider how Daumier uses the medium’s tonal range to evoke the grimy reality of this setting, reflecting their socio-economic reality, so different from other portrait artists of the era who created glamorized and romanticized images. The softness blurs harsh lines and class division, encouraging us to empathize with these people rather than see them as a faceless crowd. Editor: That’s a great point. Thanks, I never looked at it this way before! Curator: My pleasure! There's always more to unpack!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.