print, engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

baroque

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

form

#

portrait reference

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 511 mm, width 410 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

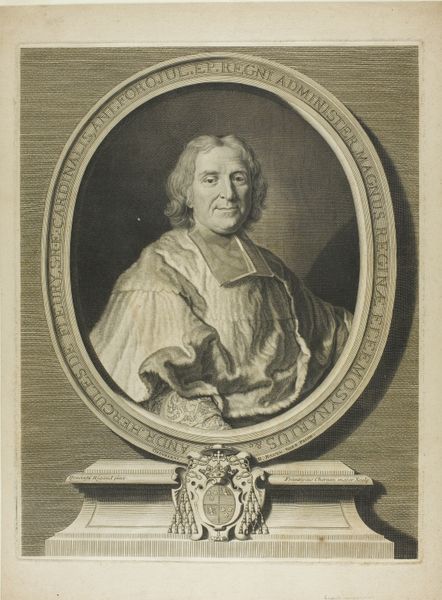

Curator: Look at this print, an engraving of Emmanuel Théodose de la Tour d'Auvergne by Pierre Drevet, placing him in a Baroque setting sometime between 1673 and 1738. It's housed right here in the Rijksmuseum. What catches your eye? Editor: It’s remarkably gentle, considering it's a portrait of a man of power, framed within all that imposing Latin text. There's an underlying vulnerability in his expression, as if we've caught him off guard, amidst his official role. Curator: It's fascinating, isn’t it? Drevet was known for his technical skill, his ability to capture not just likeness but also status and character. The oval frame, almost a looking glass, presents de la Tour d'Auvergne as if he were right here with us. He embodies prestige and solemnity. Do you think that reflects an archetype? Editor: Undeniably. Think of the circle – it's ancient, primordial. The cyclical nature of power, rebirth, the eternal return… it implies that even individual fame dissolves into the vastness of history and repeats over. And the coat of arms at the base only intensifies this effect. Curator: The use of engraving here, all those intricate lines, feels significant too. Each one carefully placed, contributing to both the detail of the face and the overall solemn atmosphere. One might read his attire like visual script. The white collar of the clergy signifies purity, obviously. It's like a calculated vocabulary of status. Editor: Precisely! Each detail a word in a visual language of authority. His gaze avoids ours directly; perhaps indicative of how removed he is. And yet, those slightly weary eyes, maybe speaking to us across centuries of the burden carried. Does Baroque art really capture life, I wonder, or is it all artifice? Curator: It walks the line, doesn’t it? Between glorifying its subjects and hinting at the human condition beneath the surface. The technical mastery alone invites prolonged observation, revealing subtleties you might miss at first glance. A portrait of someone meant to impress, viewed centuries later, becomes an evocative expression. Editor: Yes. I entered expecting rigid formality, but I leave feeling a sense of quiet communion with the imprint of a historical figure. His emblems have lost their voice to me, but his gaze strangely has gained some.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.