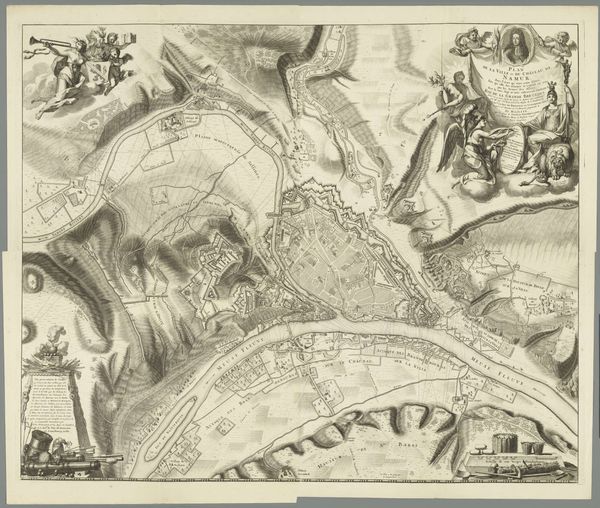

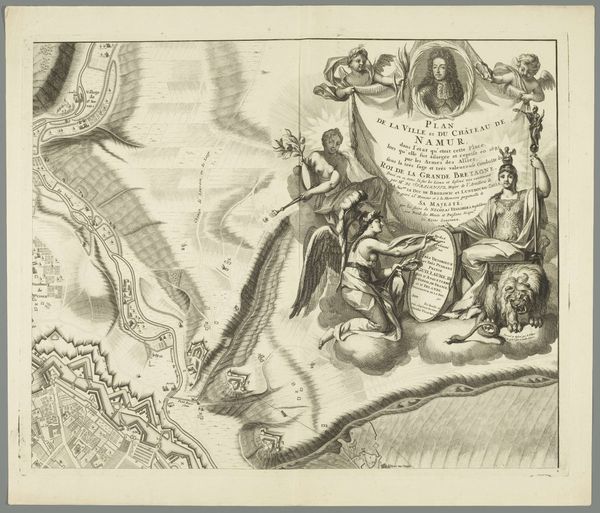

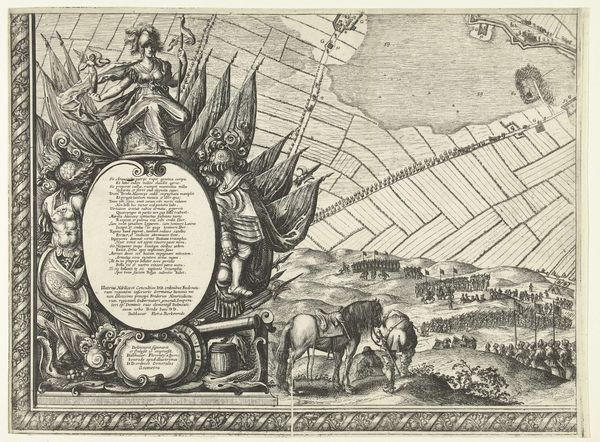

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

linocut print

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 540 mm, width 630 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

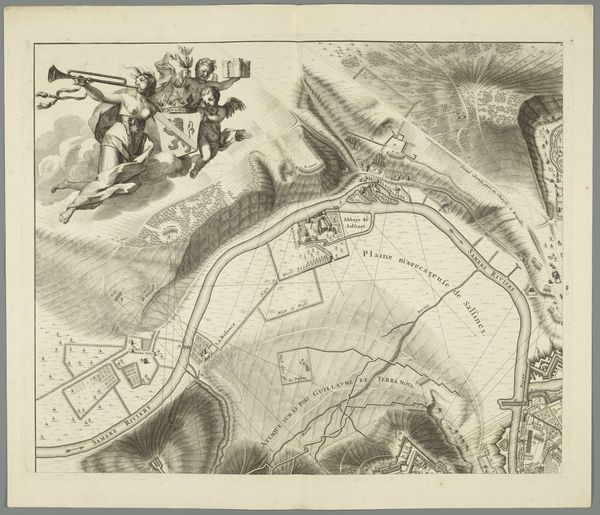

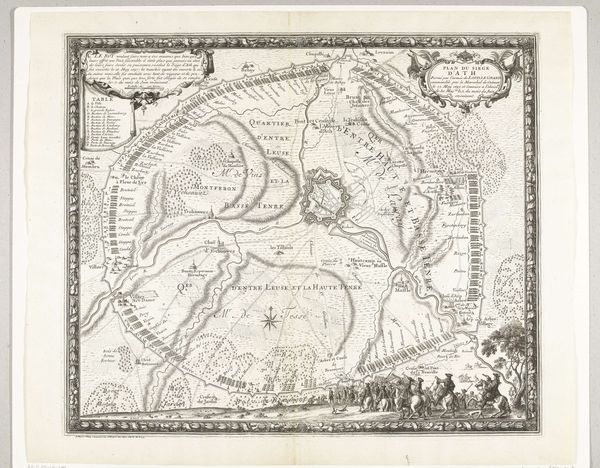

Curator: Here we have “Grote kaart van het beleg van Namen (blad nr. 3), 1695,” or “Large Map of the Siege of Namur,” created in 1695 by Gilliam van der Gouwen. This is one sheet of a larger print, and the Rijksmuseum holds this particular piece in its collection. Editor: It’s stark, isn’t it? Almost chilling. All these meticulous lines etched to illustrate the details of warfare. It's hard to reconcile such graphic visual precision with the chaos that conflict entails. Curator: Precisely. Note the prominence of the fortress itself. Throughout history, fortifications are not merely structures of defense, but symbols. Namur stood as a crucial stronghold; its capture held immense strategic importance for both the French and Allied forces. Its image represents military power and territorial control. Editor: The siege itself becomes a narrative woven with violence and ambition. And the cannons dominate the foreground, framing our perspective. How do you think such an image worked at the time? Curator: As propaganda. But also, as a means to assert power and convey its dominance, not just territorially, but psychologically. A way to document what was conquered but also to control its memory. Editor: The scale of devastation reduced to neat lines, rendered understandable—and justifiable—within an easily consumable, ordered format. This kind of rendering has profound implications on who got to experience these images, as not all could. Curator: Indeed, this connects with symbolic lineage. Throughout history, depictions of power, especially those showcasing dominance through control over land or populations, echo within one another across vast stretches of time. One reads something of earlier Roman maps here. Editor: Exactly. This image, in its time, was meant to serve very specific colonial interests. I'm curious about what futures we want to envision for such contentious art in the museum today. How might our viewers respond, in productive, socially generative ways? Curator: The questions you raise underscore how powerfully these images resonate across centuries. The iconography serves both to solidify power structures but also potentially to be questioned.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.