drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

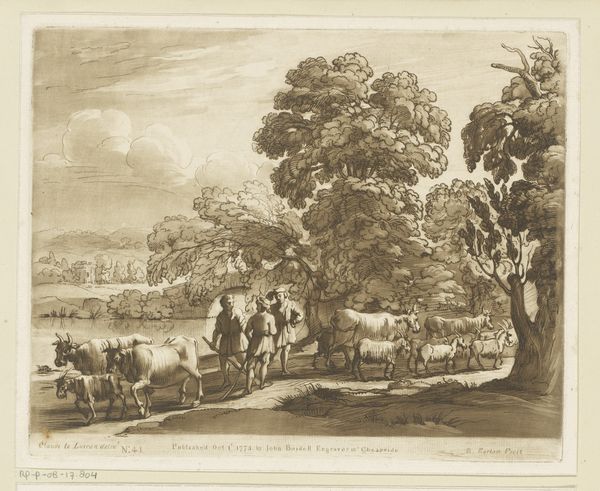

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 3/4 × 9 1/8 in. (17.1 × 23.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching, “Latona and the Lycian Peasants,” was created in 1649 by Wenceslaus Hollar. It depicts a scene pulled straight from Ovid's "Metamorphoses". What strikes you about it? Editor: My initial impression is one of dynamic tension. The bucolic landscape in the background offers a sense of serenity, yet the figures in the foreground are embroiled in a dramatic interaction, the men bending at the pond and the regal figures watching from the shore. Curator: That contrast is central to the print’s appeal and function. Hollar made the work during a particularly unstable period. The image connects that unrest to the myth. Ovid’s story illustrates the goddess Latona, mother of Apollo and Diana, being mocked and denied water by Lycian peasants. As punishment, she transforms them into frogs. The peasants you noticed are indeed in the throes of their transformation. Editor: So the frogs represent not merely an insult, but a cosmic imbalance corrected? Frogs themselves, from ancient Egypt to modern fairy tales, are potent symbols of transformation. We are looking at the shift from human to animal as a sign of the peasantry being lowered in stature through this literal animalistic shift. Curator: Absolutely. Hollar created this piece at a moment of social transformation too, of course. This piece subtly reinforced notions of social hierarchy. Hollar worked under the patronage of the English aristocracy, even following them into exile during the English Civil War. These myths, these visual commentaries, become crucial to understanding the prevailing views of power, divine right, and the consequences of challenging established authority. Editor: It’s remarkable how this relatively small print contains such complex socio-political messages, amplified by its reliance on pre-Christian symbology. Curator: Exactly. By visually connecting the upheaval of his time to a classic myth, Hollar gave the anxieties of the aristocracy a grand, historical frame. A framed anxiety, in more than one sense, if you will. Editor: A potent reminder that even seemingly simple landscapes can be battlegrounds for power and perception, mirroring broader social shifts in that very time. Curator: Precisely. The print offers more than meets the eye in regards to understanding the art and life in seventeenth century Europe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.