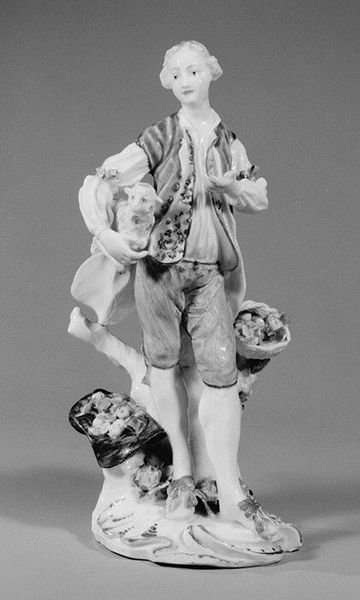

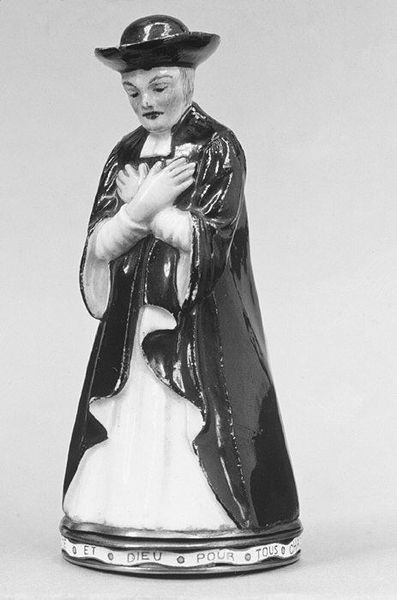

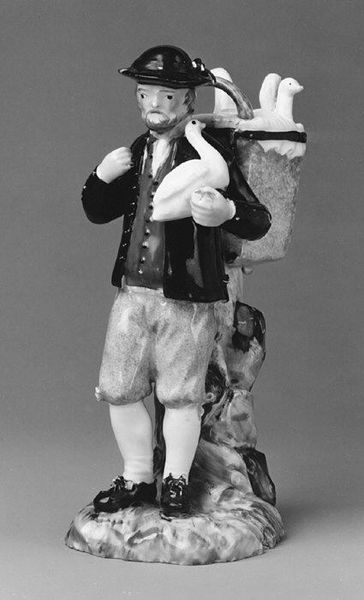

ceramic, sculpture

#

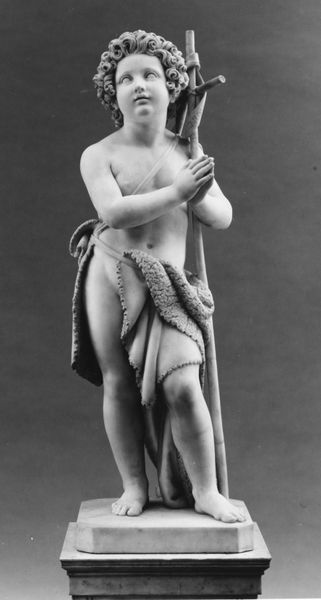

sculpture

#

ceramic

#

boy

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

black and white

#

genre-painting

#

decorative-art

#

rococo

Dimensions: Height: 5 in. (12.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This porcelain sculpture, titled "Boy," was crafted sometime between 1755 and 1775, and attributed to the Niderviller factory. It currently resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you initially? Editor: A sense of melancholic gentility. He's got a brace of birds, hinting at a successful hunt perhaps, but the bowed head and slight slouch suggest a weight beyond his years. Curator: Niderviller, under the leadership of Count Adam-Philippe de Custine, produced pieces that catered to the aristocracy. This figure, paired with a companion piece depicting a girl, speaks to the vogue for genre scenes popular in decorative arts of the Rococo period. Editor: That context makes the figure even more intriguing. The pose feels carefully constructed to elicit empathy. The brace of birds adds a layer – are they symbols of vulnerability, his own lost innocence, or perhaps even the spoils of a class system? Curator: Rococo was about pleasure, and the commodification of everything. Even innocence became a precious object. Do you see echoes of this here? Editor: Certainly. He is posed like a classical figure but presented in these very contemporary clothes. So even in mimicking idealized beauty, we understand his particular moment. But also, I can't help but feel a discomfort knowing this object likely decorated the halls of someone quite powerful, who would have sentimentalized him for their own gratification. Curator: Exactly. And isn't that dissonance key to understanding Rococo? The aesthetics of idyllic leisure masked, sometimes thinly, a social structure defined by profound inequality. These sculptures remind us that visual appeal doesn't exist in a vacuum. It reflects—and often reinforces—the values of its time. Editor: The piece’s emotional complexity persists across the centuries, doesn’t it? It’s a reminder that these objects, beyond their beauty or technical skill, were actively participating in the construction of ideas about childhood, class, and power. Curator: Precisely. When we look closely, the figure speaks to that historical context with surprising eloquence, beyond simply being aesthetically pleasing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.