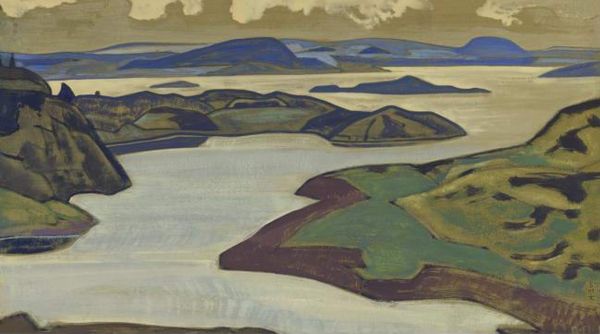

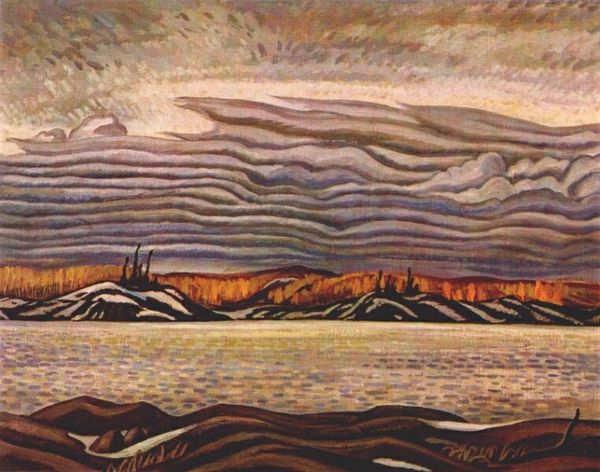

Copyright: Public domain

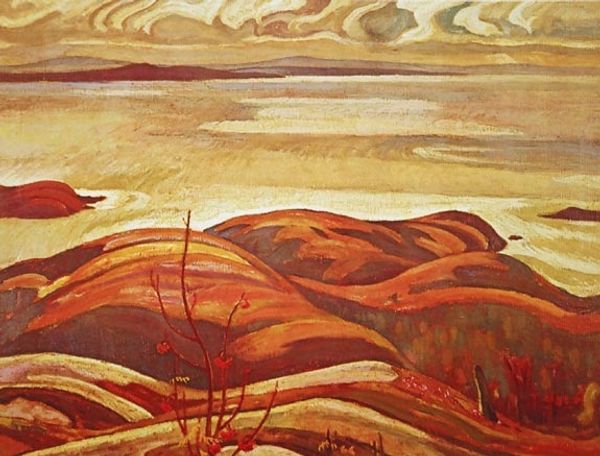

Curator: Let's discuss Franklin Carmichael's "La Cloche Panorama" from 1939, painted en plein air using oil. The scene depicts a sweeping view of the La Cloche mountain range in Ontario, Canada. Editor: The initial impression is striking. There’s a kind of rough beauty here. It almost vibrates with a suppressed energy—the clouds feel heavy, like they’re pressing down on the rugged landscape. Curator: Carmichael was a founding member of the Group of Seven, deeply invested in creating a distinctly Canadian art. This piece showcases his characteristic style – bold brushstrokes and a simplified, almost stylized, representation of nature. Editor: Exactly! But it’s not just about aestheticizing nature; it's about a particular cultural relationship to it. The "untamed" Canadian landscape, particularly during that era, was heavily romanticized as this space for masculine adventure and rugged individualism, often glossing over indigenous perspectives. Does this fit into that trope? Curator: To an extent, yes. The Group of Seven certainly participated in constructing a nationalist narrative. However, I think Carmichael’s personal connection to the land – his sensitivity to its forms and textures – complicate a purely ideological reading. It's a complex relationship, embodying both reverence and a kind of possessive claiming of the landscape. The impasto application creates such movement, drawing the eye across the canvas. Editor: True, the paint itself becomes almost topographic. But what about the narrative it subtly excludes? Considering the ongoing debates around land rights and indigenous sovereignty even now, the depiction of empty wilderness carries its own weight, doesn’t it? It silences those historical and present claims. Curator: That’s a valid point. Viewing this now, we need to consider that omission and challenge that colonial gaze inherent in so much landscape art of this period. Carmichael's rendering of the Canadian wilderness has played a huge role in Canadian self-identity. Editor: It does make you consider what stories these beautiful yet politically loaded landscapes actually tell, and who gets to tell them. Thinking critically about landscape painting from the colonial era can really push our understandings of land and ownership.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.