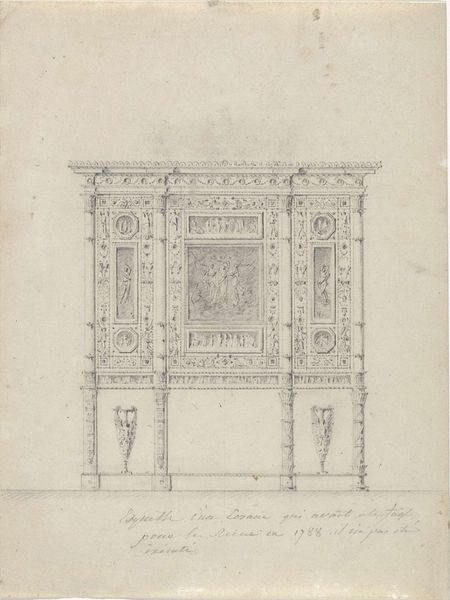

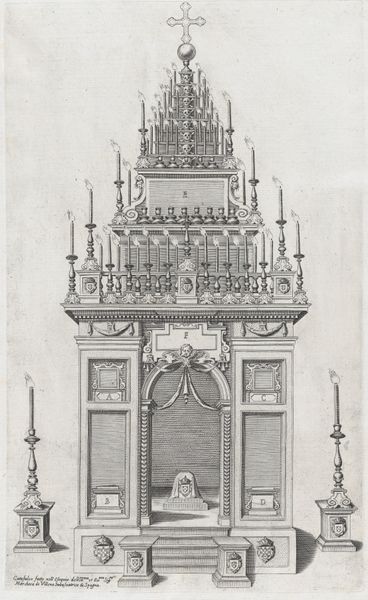

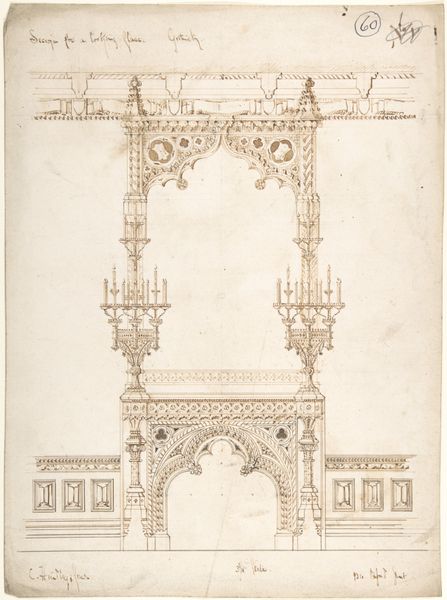

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 215 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

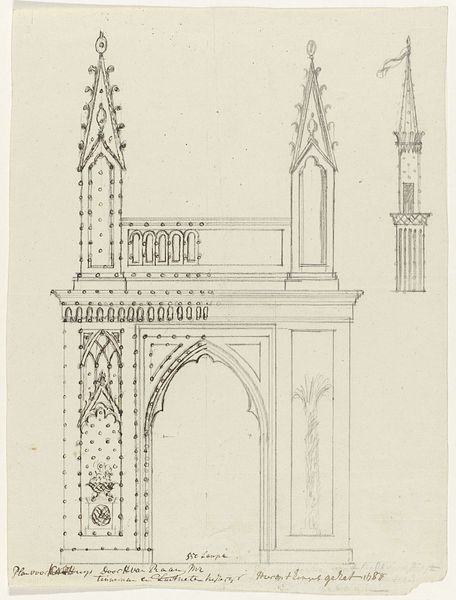

Curator: This print, entitled "Kast," meaning cabinet, dates back to before 1870. It's attributed to David van der Kellen, and the Rijksmuseum is its current home. It's an engraving rendered in ink on paper, showcasing remarkable detail. Editor: My first impression is how delicate this piece feels. The lines are so fine, almost ethereal, giving the cabinet a surprisingly light appearance despite its presumed solidity. Curator: Indeed. The labor involved in creating such intricate line work through engraving is noteworthy. Think of the craftsman meticulously etching away at the plate to produce this design, echoing the labour that would go into actually producing the cabinet itself. We often overlook these processes. Editor: It does bring into question the relationship between craft and art. This print functions both as a document of an object and as a unique aesthetic statement. One might view the cabinet as functional furniture. But the artist makes clear it could become more like architectural decoration. Curator: Precisely. It seems to draw from the visual language of the Gothic, visible in the arches and ornamentation. Do you think this is trying to claim it as something more important through the history that style carries with it? Editor: Absolutely. Gothic architecture historically communicated the Church's immense authority, visually asserting power and hierarchy. By adopting that visual style here, in an age where Gothic architecture and religion are more nostalgic than practically in power, there seems an act of reaching towards lost power by imitation. Even the presentation implies hierarchy—the cabinet's ornate facade shields and encloses its contents, implying controlled access and a clear delineation between the seen and unseen. Curator: Thinking materially, the print is a form of reproduction, of consumption itself. What once existed, the cabinet, perhaps a luxury item in itself, can exist perpetually on a page. What are we consuming and buying when we get this work as an owner now? Editor: It also plays into ideas of privacy, something the Dutch golden age struggled with even while espousing domestic life. This print provides that glimpse, a potential way to "own" an intimate view otherwise unaccessible to the wider world or market of art consumption. Curator: A compelling point about domestic intimacy in that historical moment. Thank you for opening up these threads for consideration, looking at the making itself through both material and narrative ways! Editor: And thank you for the deep dive into the materiality of its creation. Always essential for seeing what really is valuable about these underseen pieces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.