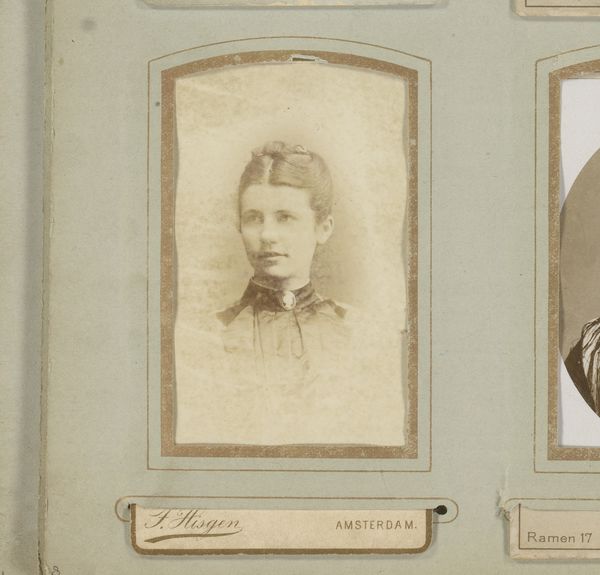

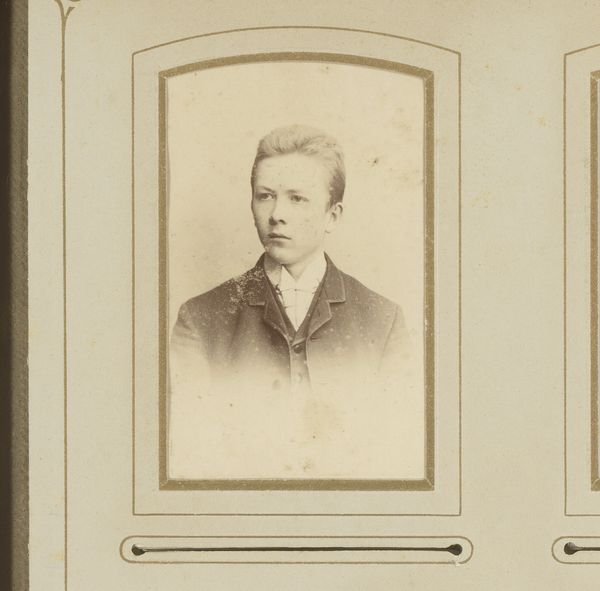

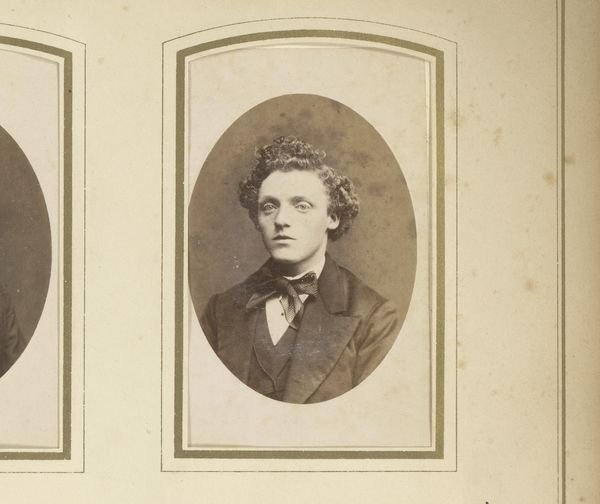

photography

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Portret van een vrouw," created sometime between 1861 and 1874 by Albert Greiner, now held in the Rijksmuseum, my initial response is one of reserve. It’s a photograph, and there’s a stillness, almost a fragility, conveyed through the tones. Editor: Yes, there’s a quiet austerity to it, a sort of muted formality inherent to portraiture from that period, perhaps reflecting a broader culture. I’m immediately drawn to think about the identity of this woman. Was this a commissioned piece, for example, indicative of her status in society, and to what extent might gender and class shape the artwork? Curator: Formally, the photograph presents a careful composition. Note the balance between the detail in the face and the softer focus of the background; it subtly directs your gaze. Semiotically, we might even consider the jewelry, the velvet collar, and the elaborate hairstyle. What do they suggest to you? Editor: They are, undeniably, coded signifiers of the 19th-century bourgeois woman—objects deployed as statements, but also perhaps constraints within patriarchal systems. To me, the image also speaks to the power dynamics inherent in the photographic process itself, and the sitter's lack of agency over how she is portrayed, reflecting deeper historical inequalities. Curator: Indeed. Yet Greiner's composition draws the viewer in, despite the obvious conventions of studio portraiture, through its technical skill in rendering the play of light. Considering photography's nascent stage then, how do you see it negotiating between art and science? Editor: Well, the question for me is whether such art-science dualism actually matters. Viewing this photographic portrait allows for broader intersectional narratives beyond formal constraints: questions about authorship, gender roles, and the historical representation of women. Perhaps it prompts us to think critically about who has traditionally been left out of art-historical narratives. Curator: Absolutely. Thank you for that insightful reading of its broader implications. Editor: Of course. A photograph like this prompts essential dialogues about identity, agency, and historical power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.