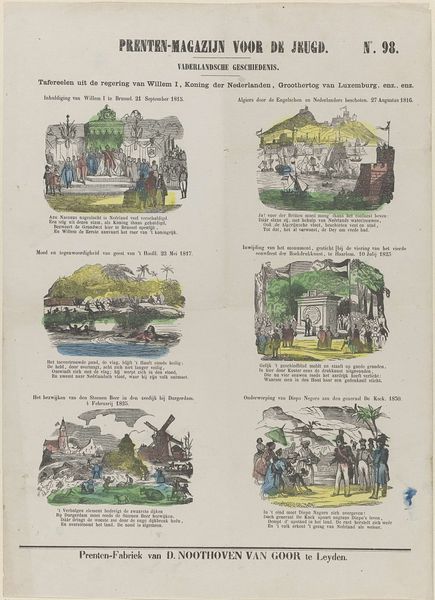

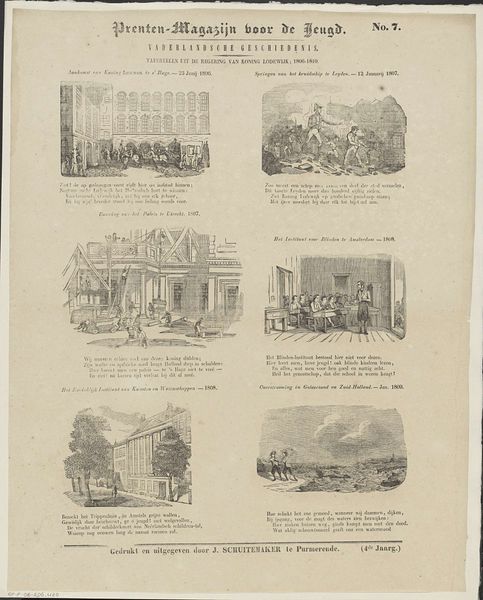

Tafereelen uit de regering van Willem II, koning der Nederlanden, groothertog van Luxemburg, enz. enz. enz. 1850

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

# print

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 426 mm, width 334 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

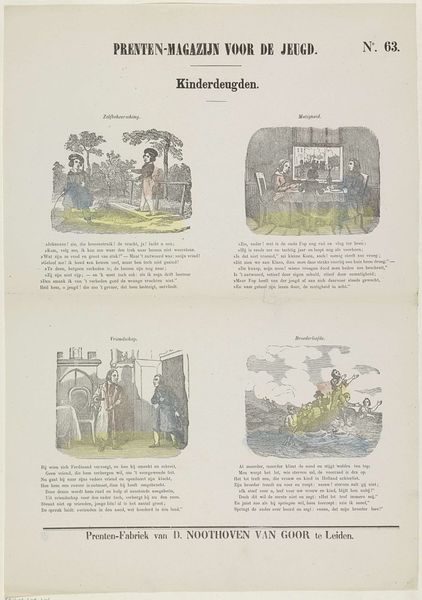

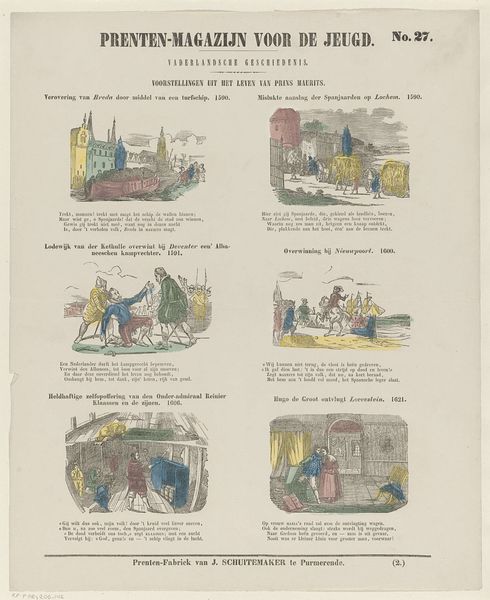

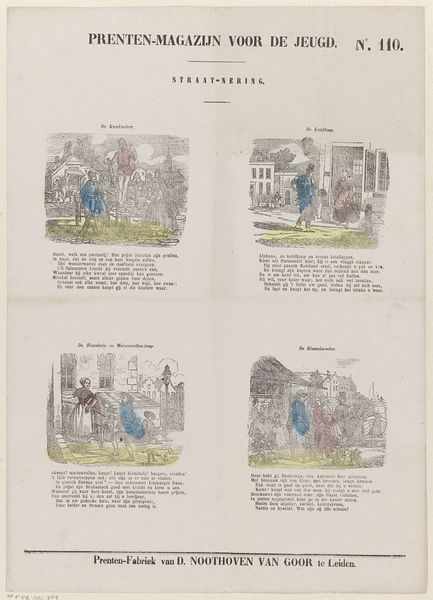

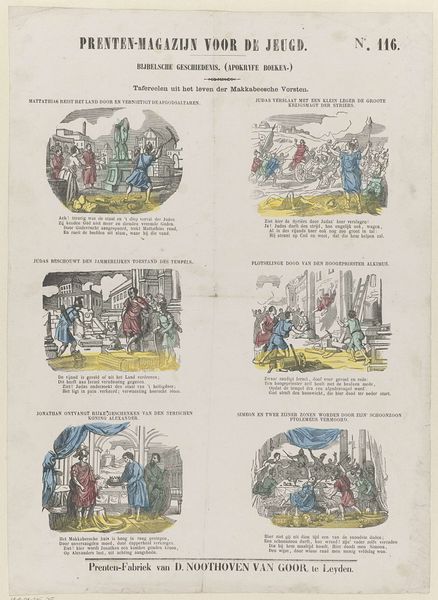

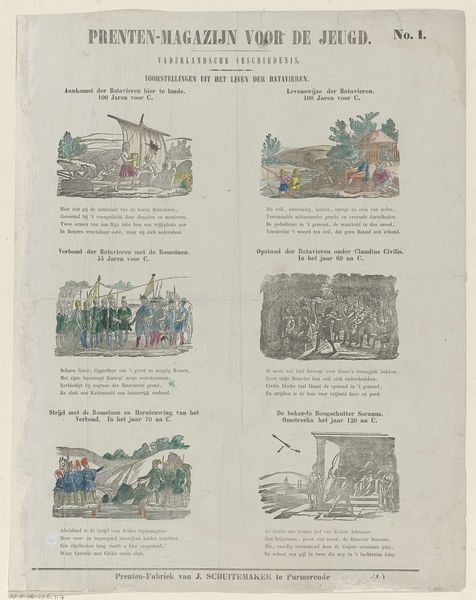

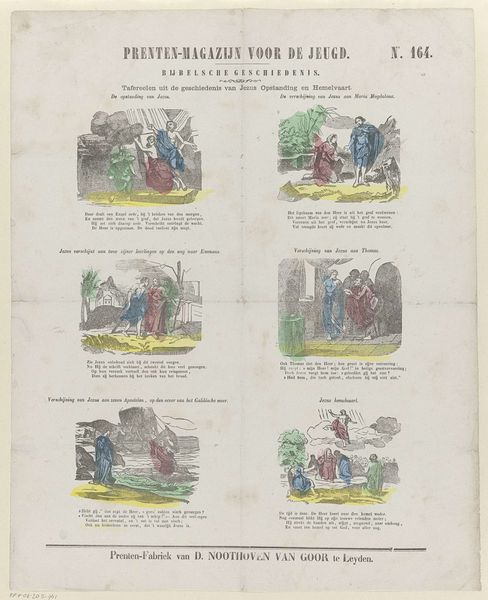

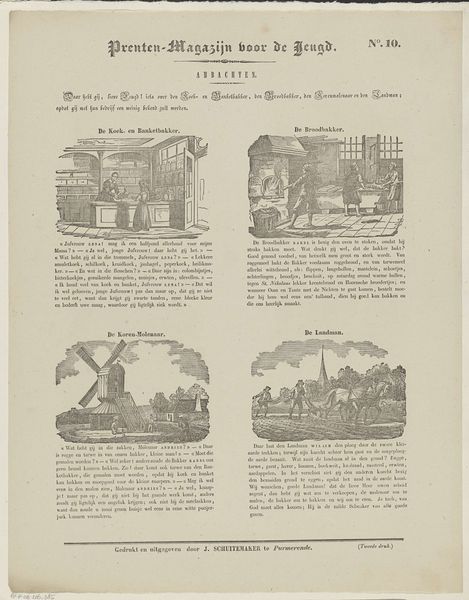

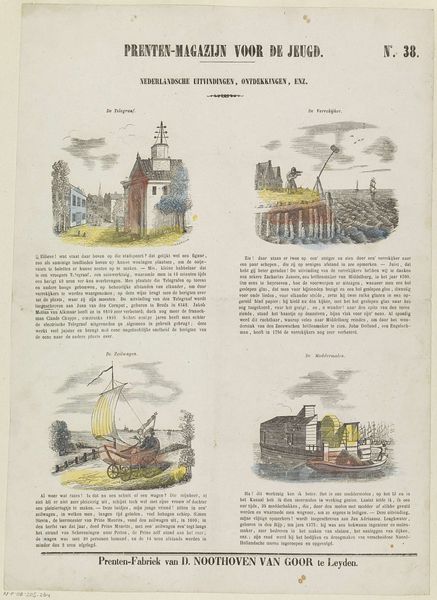

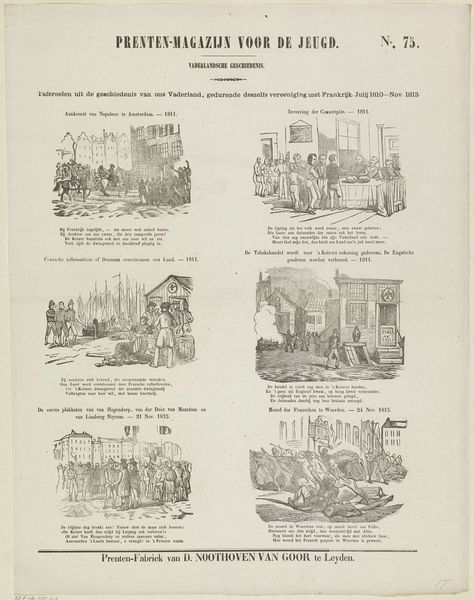

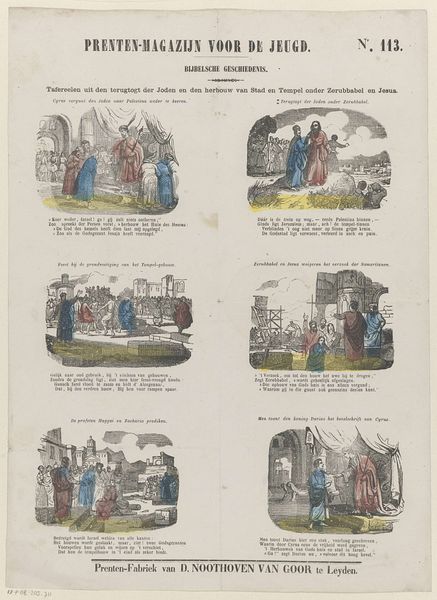

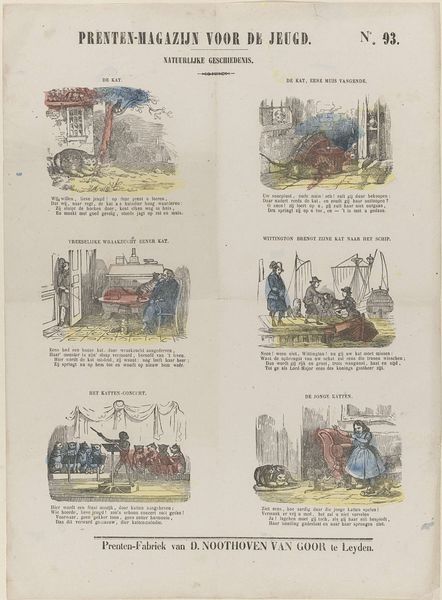

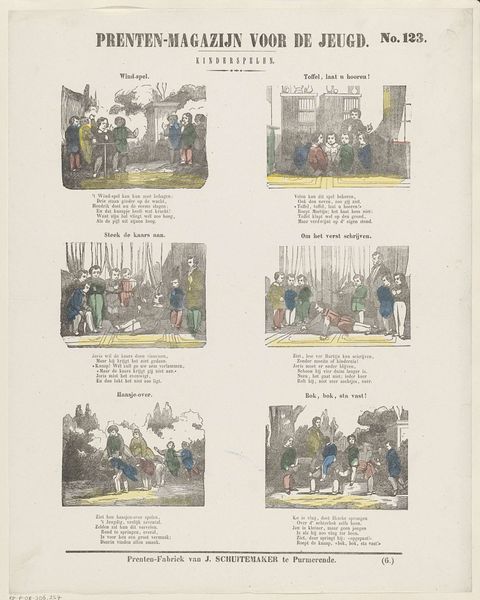

Curator: Ah, this print immediately catches my eye. There's a naive charm to the layout and colouring; it reminds me of old textbooks, of flipping through historical accounts in childhood. The scenes are rendered in these pastel shades. Almost childlike. Editor: This is “Tafereelen uit de regering van Willem II, koning der Nederlanden, groothertog van Luxemburg, enz. enz. enz.” roughly translated to "Scenes from the Reign of William II, King of the Netherlands, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, etc. etc. etc.” created in 1850 by Jan Schuitemaker, printed as an engraving. It seems like a precursor to the picture essays in our news today. A history lesson made palatable. Curator: A political cartoon! That's what it looks like. See how William the First departs from the throne and makes way for William the Second, along with a bunch of pomp and circumstance involving stately looking buildings and waving flags. History told like a children's rhyme. It does simplify things, I wager, but it definitely makes the grand narrative accessible. Editor: Well, that was its purpose. We have to think about Romanticism, how it intertwined with a burgeoning sense of national identity. Schuitemaker presents the major events: The new king taking the reins, grand openings of national projects like the Willemspoort, royal inaugurations in Amsterdam… all building a heroic narrative. Curator: So it’s propaganda then! The question is, how much of it did people actually take seriously? You know, art and politics: always an uneasy dance. Perhaps viewers saw straight through it. Or maybe, the art simply fed what they already wished to believe, turning myth into “fact”. Editor: And think about who saw it. It’s titled, isn't it, as a "Prenten-Magazijn voor de Jeugd,” a print magazine for children? Schuitemaker isn’t appealing to high society; it's shaping young minds, defining Dutch identity for a new generation. What stories were told? Who are the protagonists and antagonists? Those images sink in deeply. Curator: Exactly. Well, this work offers me, at least, a new appreciation of propaganda. This feels less cynical than contemporary versions. There's something almost quaint in its desire to simply ignite love for the fatherland. What about you? What feelings does it awaken? Editor: A fascinating intersection between art, power, and nation-building, crafted for children and the masses. Food for thought!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.