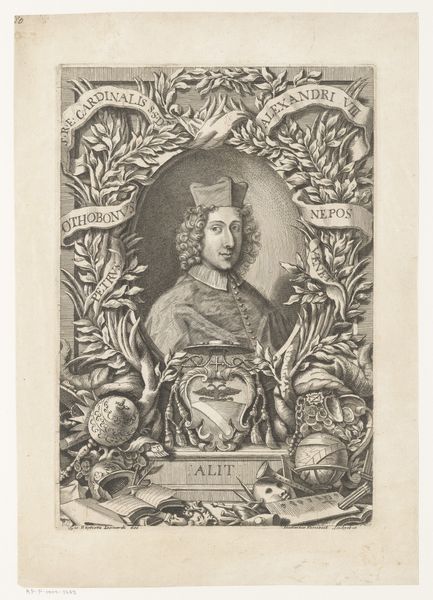

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 305 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a portrait, an engraving, of Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, created around 1692-1695 by Frans Bouche. I'm struck by how staged it all feels – the armor, the elaborate wig, the regalia… It makes me wonder, how much of this is about projecting an image of power? Curator: That's a perceptive observation. In the context of the late 17th century, especially within the Baroque era, portraits weren't merely likenesses, but carefully constructed statements of authority. Consider how the piece utilizes classical motifs and symbols, aligning Maximilian with powerful precedents. Notice the objects, armor and crown for instance: What impression do these choices about symbolism give you? Editor: They definitely communicate strength and divine right to rule. It’s almost like propaganda. The overall message isn’t about Maximilian Emanuel the man, but about Maximilian Emanuel the ruler. Curator: Precisely. The choice to depict him in armor, the strategic use of emblems associated with the Holy Roman Empire… It all served a clear socio-political purpose. This print, readily reproducible, extended his reach and influence, even symbolically. Academic art wasn't separate from court. It often helped in identity shaping to reflect the taste of those with power. Editor: So it's less about artistic expression in a personal sense, and more about a calculated presentation designed to maintain or even strengthen his position? I guess I never really considered how prints, as a medium, could also have their own socio-political impact. Curator: Indeed. Think about the role images played in circulating power structures, ideals, and social norms during this period. Editor: I'm now viewing the art as being influenced by social elements and vice versa. Curator: Exactly, and recognizing that interrelationship is critical.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.