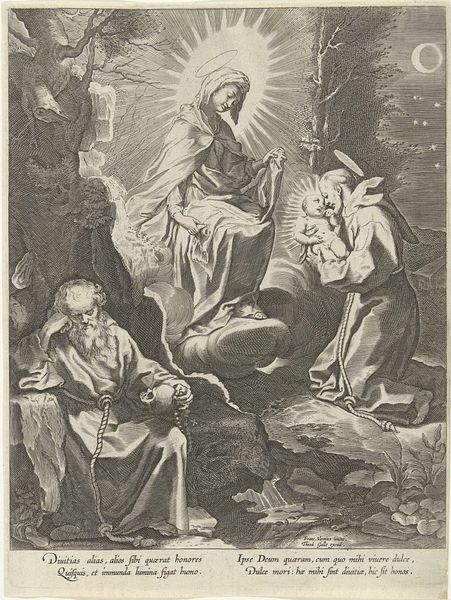

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 335 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

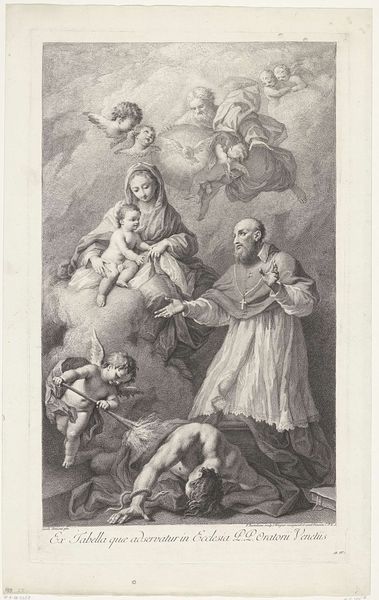

Curator: Before us is "Saint Francis Receiving the Christ Child from the Virgin Mary," an engraving by Cornelis Bloemaert, created in 1684. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What immediately strikes me is the swirling quality, a dynamic movement between earthly devotion and divine light. There's a powerful sense of emotional transport, enhanced by the theatrical use of light and shadow. Curator: Baroque engravings such as this one often served as disseminators of artistic ideas. Prints allowed for wider circulation of imagery, acting almost like a reproductive technology spreading specific interpretations and devotional acts. The sharp contrast comes from the material limitations of the engraving craft, which only allows you to either cut a line into a plate or not. The final product results from the amount and thickness of lines cut by the engraver into the copperplate. Editor: Absolutely, the imagery here is potent. Saint Francis, on bended knee, embodies humility and receives the infant Christ—a visual metaphor for divine grace. The symbolic weight is immense. The soft light radiating from the baby also recalls notions of sanctity that have been repeated throughout visual history. And look at the Virgin's serene gaze; it transmits both motherly love and spiritual authority. Curator: Beyond the symbolic narrative, it's important to recognize the labor embedded in this print. An engraver would copy the artwork from a painting or design, usually one created by another artist. It required precision, skill, and a deep understanding of the source material to produce something that looked believable. Editor: I agree; consider the angels nestled in the clouds. They’re common, yes, but look closer, their chubby forms contribute to a sense of otherworldly drama and underscore the importance of the event. It speaks to enduring needs for solace and transcendent beauty through religious symbology. Curator: For me, examining such prints provides insight into both the artist's technical skill and the wider world of labor connected to art-making. We are used to looking at grand paintings, but works on paper allow one to glimpse the usually invisible artistic workforce of the seventeenth century. Editor: I come away appreciating how Bloemaert translated a profound spiritual encounter into a tangible image that, despite its limitations, transcends material. Curator: And that speaks to the collaborative processes by which the images reached the world. These artworks only existed because many specialized artisans worked together to fulfill their commissioner’s demands.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.