Dick Hughes, Shenango Ingot Molds (Working People series) 1987

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 17.6 x 14 cm (6 15/16 x 5 1/2 in.) sheet: 25.2 x 20.2 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

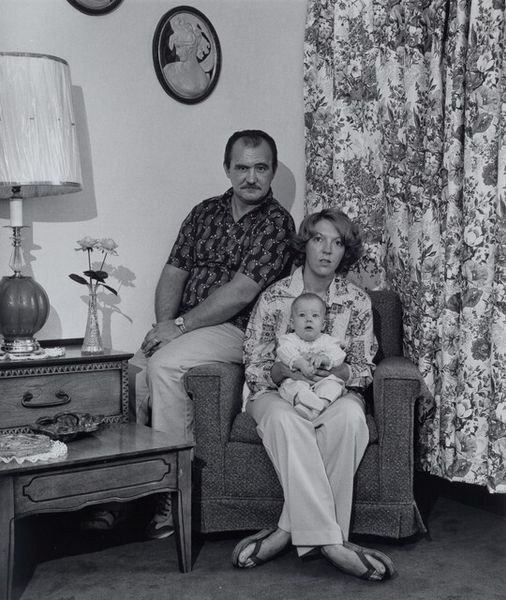

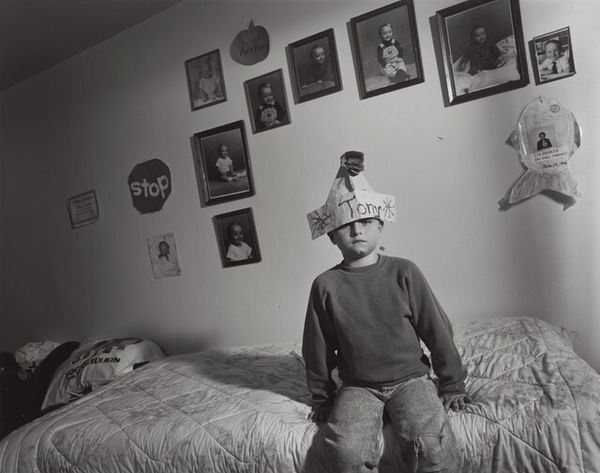

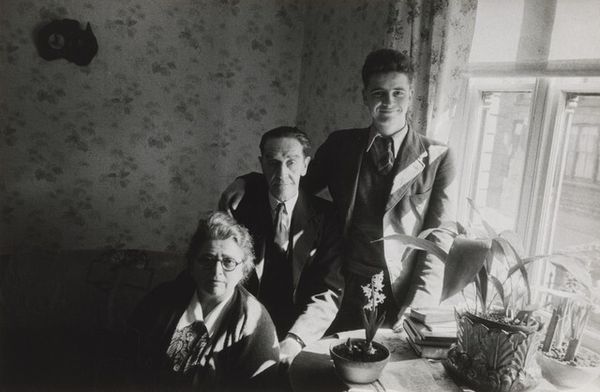

Editor: Here we have Milton Rogovin’s 1987 gelatin silver print, "Dick Hughes, Shenango Ingot Molds," part of the "Working People" series. It feels incredibly intimate and direct, a simple yet profound portrait. What do you see in this piece, beyond the surface? Curator: I see a powerful commentary on labor, class, and the everyday dignity of working-class individuals. Rogovin's choice to photograph Hughes in his home situates him within the context of his personal life, not just as a worker. The arrangement of objects – the clocks, the family photos – speak volumes about values, history, and identity formation within a specific social milieu. This challenges the notion of a singular American identity, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. The objects in the background definitely enrich the image. Do you think Rogovin was intentionally trying to make a political statement? Curator: I believe Rogovin was deeply aware of the political implications of representing marginalized communities. By focusing on the faces and environments of working people, particularly in deindustrializing America, he directly challenged dominant narratives that often render such individuals invisible. He offers visibility, and therefore agency. Do you notice how Hughes' direct gaze meets the viewer's, creating a confrontation? Editor: Yes, his expression is very direct and present. He looks a bit weary but dignified. I hadn’t thought of it as a challenge, but now I see how it resists a simple reading. Curator: Precisely. And consider the monochrome aesthetic. It's not just about style; it signifies a starkness, a stripping away of superficiality to reveal the essence of his subject. This echoes documentary traditions that seek to unearth social realities. Do you think this image reframes how we think about labour and portraiture? Editor: Absolutely. It shifts the focus from idealized or heroic representations of labor to the reality of lived experience. This conversation has really helped me understand how deeply embedded social and political meaning can be in a photograph that at first glance seems very simple. Curator: And hopefully, it inspires us to critically examine whose stories are being told, and whose are being left out. It is through this continuous inquiry that art serves its most vital function.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.