drawing, print, ink, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

pen drawing

#

mechanical pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

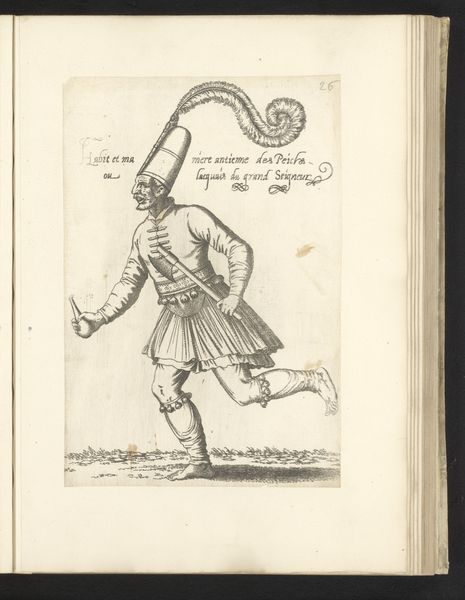

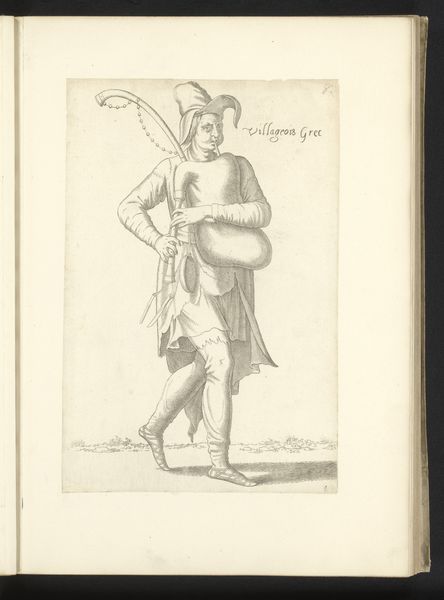

Dimensions: height 264 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

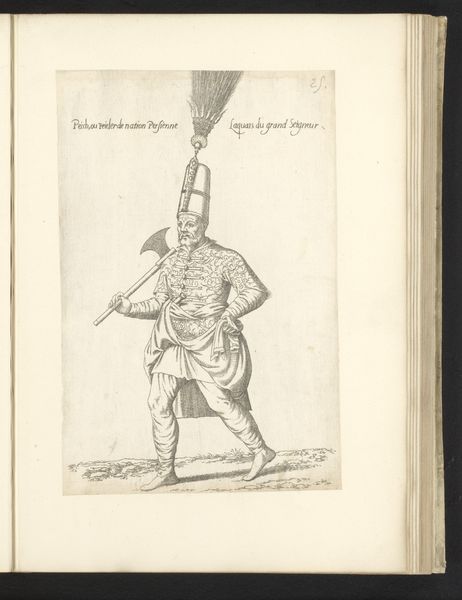

Curator: Immediately, I see power rendered with simplicity. The bold lines of the archer, almost cartoonish, convey a sense of dominance despite the figure's modest size. Editor: L\u00e9on Davent created this engraving titled "Boogschutter" sometime between 1555 and 1568. It depicts a solitary archer, prepared for action, composed with ink, pen, and engraving techniques. Curator: The towering headwear, an obvious marker of status, acts as a visual anchor, grounding the image's hierarchy. The quill-like object emerging from it, paired with the archer's tools, projects potency. This isn’t simply about military might; it’s about the power of representation, the symbolism of the instrument. Editor: Absolutely, and the cultural context of the time plays a role. Depictions of archers in 16th-century European art often symbolized military strength but also a romantic ideal, representing precision and control in the face of an unstable political world. How do you think viewers perceived the exotic style of his clothes? Curator: Ah, precisely! Clothing serves as a symbol! In this image, the archer is exoticised yet made relatable. He is foreign, evidenced by his turban, yet universally understandable because he's equipped for a task, evoking at once foreignness, but at the same time he participates in the universal act of defence and preparedness, something easily readable by every person in that period. He acts like a mythic guardian who everyone is able to comprehend, whether in awe, disdain, or fear, and that act is visually carried by that striking headdress. Editor: It's a reminder that art isn’t produced in a vacuum. Davent's "Boogschutter," circulated as a print, served not only as artistic expression, but also participated in shaping early modern European understandings of the self in relationship to what lay beyond their world, to what or who appeared foreign at the time. These prints created not only personal amusement but public dialogues. Curator: So the art becomes less about pure aesthetics and more of a vehicle for ideas of collective representation. Editor: Precisely, a microcosm of cultural perception and power. I always find that understanding an artwork's context opens avenues for thinking through the complexity of past-and present-day political power. Curator: For me, decoding those visuals, that symbol-making process, helps unlock those histories—it reveals the enduring emotional infrastructure underpinning the making of art and social values across eras.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.