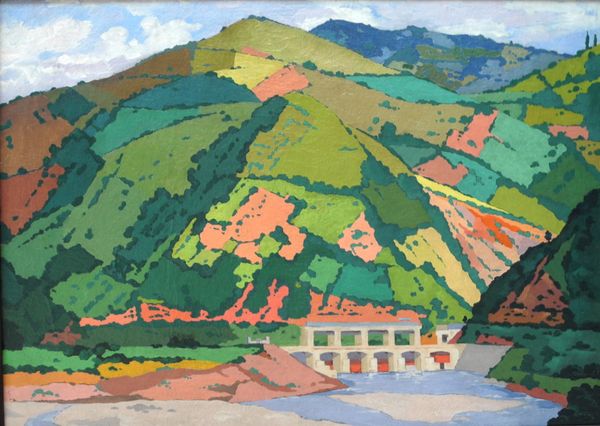

Copyright: David Kakabadze,Fair Use

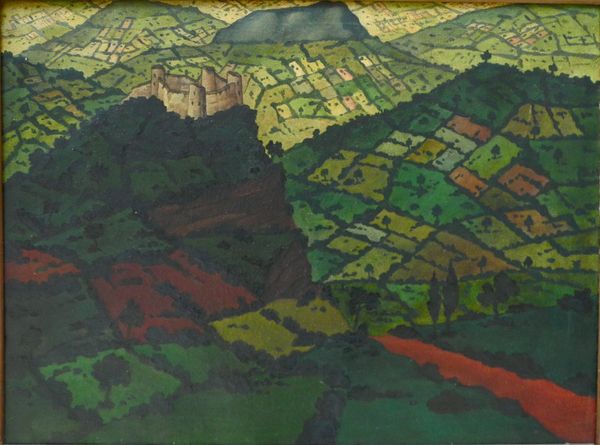

Editor: Here we have David Kakabadze's "Red Mountain," painted in 1944. It's oil on canvas and while the scene appears representational at first glance, the more you look, the more abstracted it becomes. What really jumps out is how the mountain's surface is fragmented into these angular planes of color. What do you make of it? Curator: Well, immediately, I think about the socio-political conditions surrounding its making. 1944 places it squarely within the late stages of World War II, a period marked by industrialization and massive social upheaval. The fractured planes, the seemingly arbitrary shifts in color… could these be visual echoes of a world being torn apart and reassembled? Notice the rigid, almost mechanical, application of paint. It's not about the illusion of depth, but the literal, material presence of pigment on the canvas. How does this relate to wartime economies and the efficient use of resources? Editor: So you're seeing the painting itself as a kind of artifact of its time, reflecting the industrial processes and the social fragmentation that were prevalent then? Curator: Precisely. And I’d add to that: consider the relationship to labor. The repetitive geometric shapes could be evocative of mass production and regimented labor systems. Instead of a romanticized, pastoral view, we get something that acknowledges the human cost involved in shaping the landscape and the anxieties related to a world increasingly mediated through mechanization. Editor: That makes me see it completely differently. I was focusing on the colors and the landscape elements, but you've placed it within a much wider framework of industry, labor, and war. Curator: And in doing so, we move beyond the idea of the artwork as a purely aesthetic object, toward seeing it as a site of social and material engagement. Editor: I never would have considered how much the process of *making* it, the very materiality of the paint, relates to everything else. Thank you! Curator: It’s been a pleasure showing you a way to engage more fully with what is in front of you by looking to what produced the object itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.