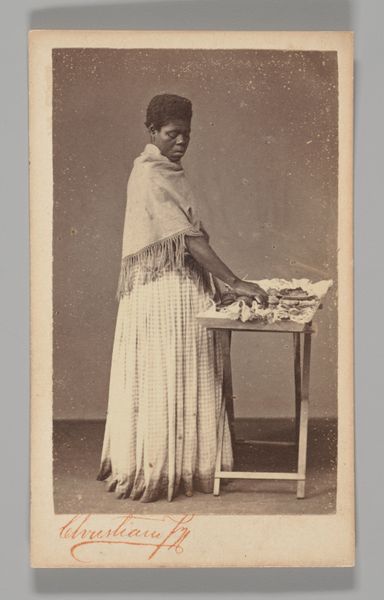

![[Studio Portrait: Seated Woman and Standing Boy Street Vendors with Vegetable Baskets, Brazil] by Christiano Junior](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzJiNTA0YzBmLTA4NDEtNGYyOC04YmU0LTc5ZDhmMmM3NGVlOS8yYjUwNGMwZi0wODQxLTRmMjgtOGJlNC03OWQ4ZjJjNzRlZTlfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

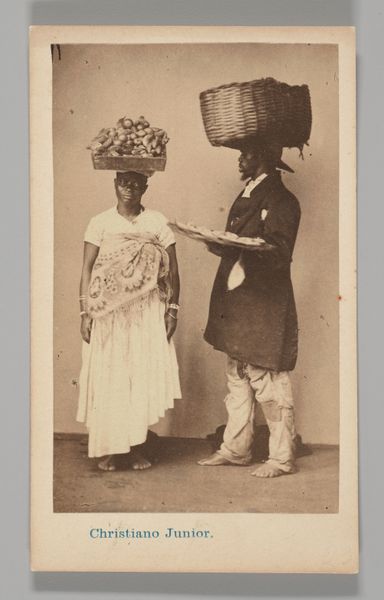

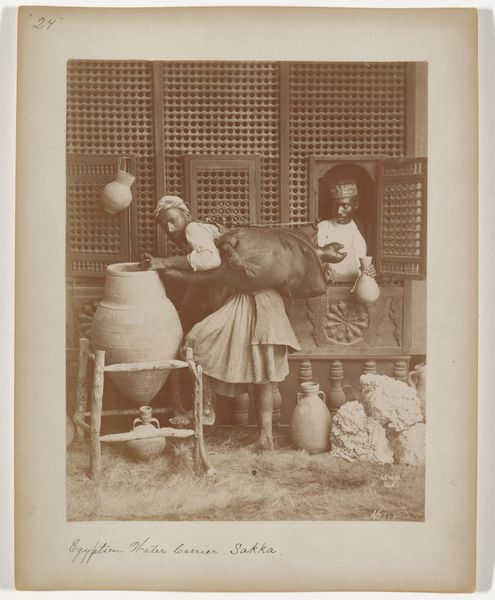

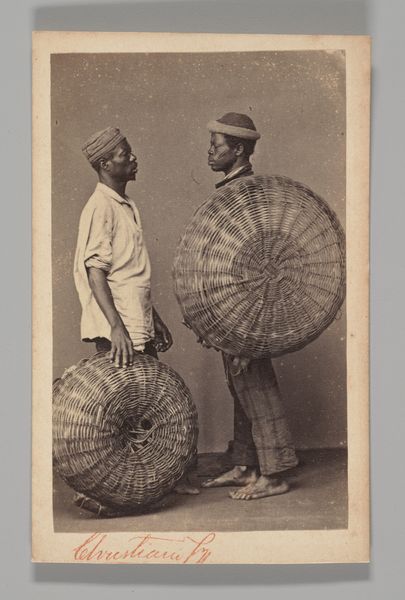

[Studio Portrait: Seated Woman and Standing Boy Street Vendors with Vegetable Baskets, Brazil] 1864

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 9.2 x 5.4 cm Mount: 10.0 x 6.2 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

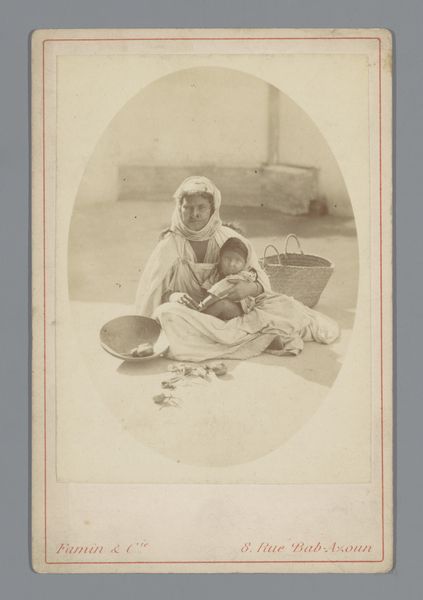

Curator: Looking at this sepia-toned image, I'm immediately struck by the apparent stillness and formality. Editor: And I notice right away the contrast of textures—the smooth fruit, the woven baskets, the cotton clothes. It begs the question, what labor went into all of this? Curator: Precisely. This is a studio portrait taken in 1864 by Christiano Junior, entitled "[Studio Portrait: Seated Woman and Standing Boy Street Vendors with Vegetable Baskets, Brazil]". We see a woman seated and a boy standing, surrounded by their produce, all likely staged for the photograph. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Given the date, these would be formerly enslaved people in Brazil, barely a decade after abolition in Britain. What kind of economic power, then, did access to the materials to practice their trade, like the woven baskets and even the fruits, suggest? What were the limitations? Curator: Absolutely. I read this image as an intersectional narrative on race, labor, and gender, particularly within the context of 19th-century Brazil. The subjects are carefully posed, and that staging can be read as an early form of resistance. They are asserting their presence and demanding to be seen in a certain way. How might these subjects have seen this photograph? How might this photo participate in the cultural and economic negotiations around race in the Brazilian context? Editor: Staging as resistance, interesting! I hadn’t thought of it like that before, as a disruption in labor and the creation of an almost artisanal identity of their making. Curator: It reminds us of the complex role photography played then, documenting everyday life, but also shaping perceptions, sometimes reinforcing inequalities, other times challenging them. Editor: Indeed, the photo itself exists because of resource extraction—the mining of silver, the factory work to create the paper—and this access underscores certain kinds of global material and economic relationships, and also reveals what isn’t available to those depicted. It provides so many potential insights. Curator: Considering this portrait invites critical questioning of its creation and its place in history, leading us to examine both the immediate depiction and the enduring power dynamics at play. Editor: Looking again, it’s clear to me that understanding production opens up further paths for exploring complex colonial narratives. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.