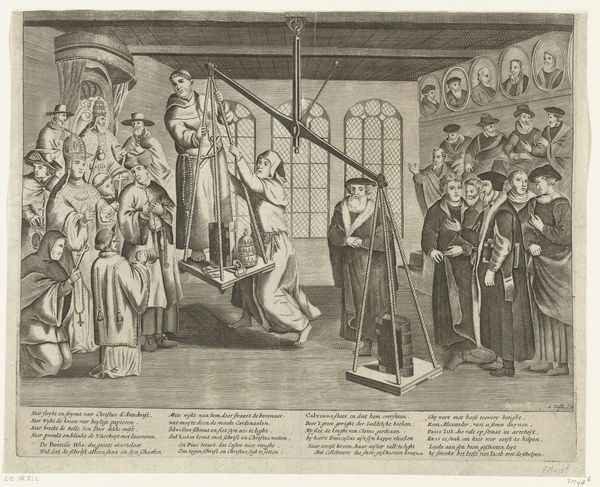

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

mannerism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 323 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

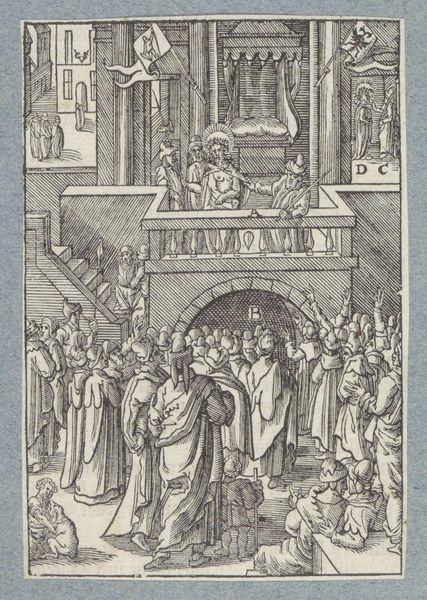

Curator: The scene before us is Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert’s “Praalbed van prins Filips Willem, 1618,” created in 1618. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Editor: It's strikingly somber, isn't it? The monochromatic tones accentuate the stark formality of the scene. You feel a certain chill just looking at the arrangement of figures around the ornate… coffin, I presume? Curator: Indeed. It’s an engraving that depicts the prince lying in state. Think about the material reality here. An engraving like this wouldn’t have been wildly accessible to all, and served less as a source of mass grief, and more like symbolic proof of dynastic heritage. Editor: Proof, exactly. Because if you zoom out from the materiality of the print itself, the image screams of political theatre. Consider the period. It's rife with religious and political tensions, and a lavish display of mourning such as this one underscores power, legitimizing the lineage in a very performative manner. Who gets access, who is mourning--it's all a matter of controlled optics. Curator: It’s a Baroque image in its ornate display, yet it clearly utilizes Mannerist techniques in the print making. Notice how every line emphasizes not realism but the constructed, elevated image. The clothing of the mourners is rendered with impressive care—a visual marker of the labour involved. Each detail reinforces the idea of order and hierarchy, etched into the very process. Editor: Precisely, and how! Consider how access to and ownership of materials contributes to cultural capital during the baroque era. It says something that Bolswert decides to commemorate Phillip Willem in this medium: controlled, reproducible, and bearing the promise of widespread distribution and lasting legacy. Curator: It really makes you wonder about the role these images played. The careful craft here tells a deeper story about both representation and societal construction. Editor: And the very act of witnessing death becomes, itself, a claim of power. In a society undergoing massive political upheaval, a spectacle such as this serves as a potent visual reminder of the old guard, solidifying privilege in the face of instability. It invites critical re-examination of the period, really.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.