The Voluntary Sacrifice of Reverend Hambroeck on Taiwan, 1662 1810

0:00

0:00

janwillempieneman

Rijksmuseum

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 102 cm, width 114 cm, depth 6 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

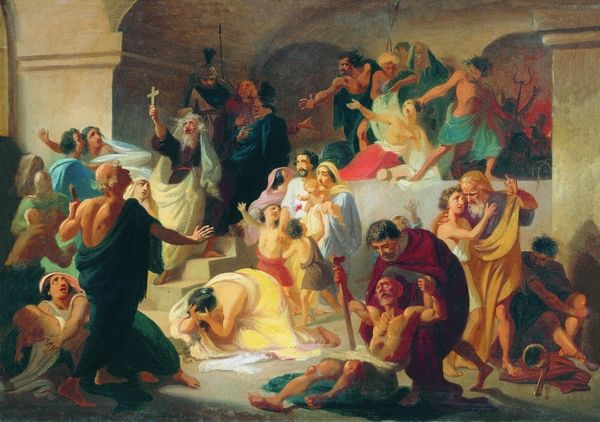

Editor: Standing before us is Jan Willem Pieneman’s "The Voluntary Sacrifice of Reverend Hambroeck on Taiwan, 1662," created in 1810 using oil paints. It's hard to ignore the stark drama; figures in distress contrast sharply with the apparent resolve of the central figure. What narratives do you see embedded in this piece? Curator: The drama, as you say, isn’t accidental. Pieneman’s work, viewed through a historical lens, served a powerful social and political function. This is history painting, but it is also actively *making* history. Consider the date: 1810. The Dutch Republic was under French control, and national identity was a fractured thing. How might a painting depicting a heroic act from Dutch colonial history function in this context? Editor: As a way to inspire a sense of collective pride, maybe? Reminding people of past glories to encourage resistance? Curator: Precisely. It uses the past to shape the present, a common function of history painting in the Romantic era. Hambroeck's supposed sacrifice—and there are different versions of the actual events—is presented as an example of Dutch virtue, of religious conviction, even amidst colonial conflict. Notice how the composition directs our gaze. Who is emphasized? Who is marginalized? How does this reflect the social hierarchies of the time, and the narratives the artist wished to promote? Editor: It's hard to miss that Reverend Hambroeck stands at the center, literally elevated above the others. The guards almost blend into the shadows, and his family are begging for his help... almost a theatrical spotlight only shines on the minister. So it uses this almost stage setting, or performance, of the event as a point of patriotic pride, rather than just historical record? Curator: Absolutely. Museums then and now play a part. By exhibiting paintings like these, national institutions helped to construct and solidify a sense of shared identity. And consider the politics of imagery - is this about one man's sacrifice, or is it, subtly or not, excusing or overlooking the brutalities of colonialism? Editor: I never thought of it that way before; it's really about using the past to say something about the present, but with complicated layers of influence. Curator: Indeed. A deeper dive into the context and the motivations really shows how historical paintings act as cultural objects within power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.