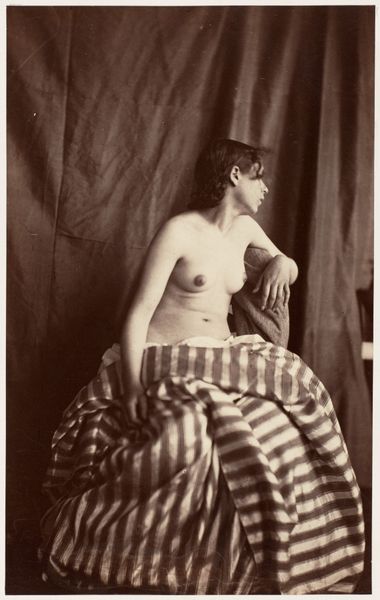

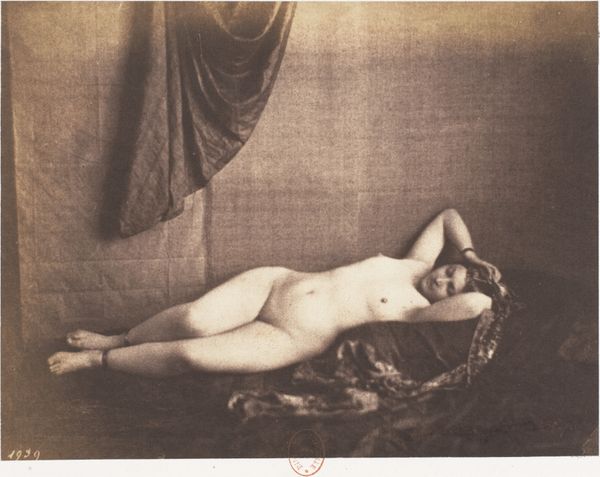

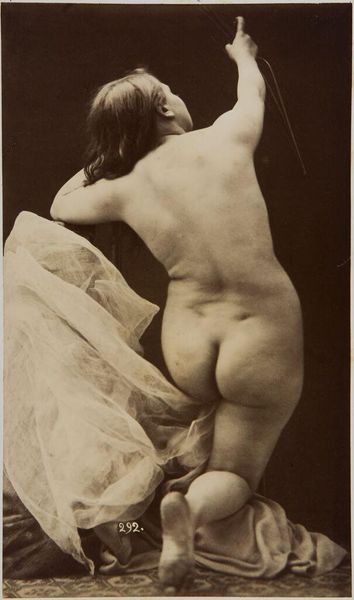

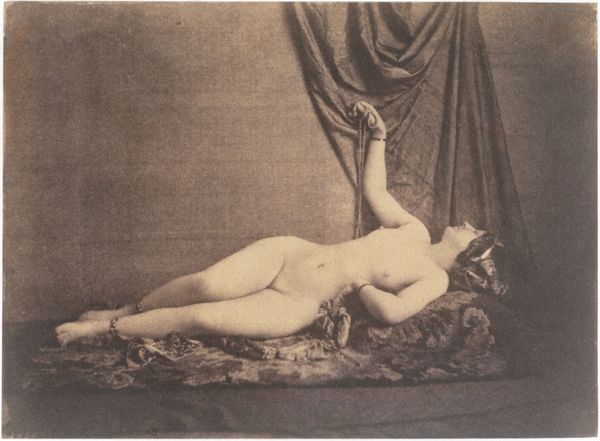

![[Seated Female Nude] by Eugène Durieu](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzJhMWQ1YzlhLThkNmEtNGU2NC1hODdiLWIzNDA0OTg4NTA1YS8yYTFkNWM5YS04ZDZhLTRlNjQtYTg3Yi1iMzQwNDk4ODUwNWFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

Dimensions: Image: 6 13/16 × 4 11/16 in. (17.3 × 11.9 cm) Mount: 13 13/16 × 10 9/16 in. (35.1 × 26.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, titled "[Seated Female Nude]", a gelatin silver print crafted by Eugène Durieu between 1853 and 1854, currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, what's your first impression? Editor: A somber vulnerability. The averted gaze, the soft draping fabric—it evokes a sense of introspection and perhaps even a hint of melancholy. It feels very intimate, almost like witnessing a private moment. Curator: Durieu's photographic nudes are fascinating when considered within the artistic and societal context of mid-19th century France. While nudes had a long-standing tradition in painting and sculpture, photography was a relatively new medium. Durieu often collaborated with Eugène Delacroix, who saw photography as an aid to painting. These works became part of debates about art’s purpose, as well as anxieties about sexuality. Editor: It's impossible to separate this image from the history of objectification, right? A woman's body, presented for the viewer's gaze, but at the same time, there's something about the soft lighting and composition that complicates that. She isn't posed in a way that overtly caters to the male gaze as typically understood. It provokes conflicting ideas of power, representation, and artistic purpose. Curator: Indeed. The muted tones, the almost classical drapery, speak to an effort to ennoble the subject. But, as you suggest, these aesthetic choices exist alongside prevailing social norms and the power dynamics of the time. The photographs produced through Durieu’s collaborations can be read as exercises in artistic investigation, anatomical study, and contributions to emerging fields of medicine, psychology, and criminology, disciplines where the status of women were defined by science and law. Editor: It makes me consider the model's own agency in the process, what did she know and feel. What agency did she have to push back if the framing and position was against her own values? Whose perspective are we really seeing? That backdrop and draping gives me a romantic painterly feel but in some respects it reminds me that it’s very clinical. Curator: These photographs offer a glimpse into a particular moment in the history of art, science, and society. They bring forward ideas related to the evolving visual culture and social perceptions of the female form in the nineteenth century. Editor: It really encapsulates the complexity of viewing historical nudes, sparking conversations about the gazes, power dynamics, and the enduring challenge of representation. Curator: A conversation we very much need to be having when looking back on our histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.