photography

#

photography

#

realism

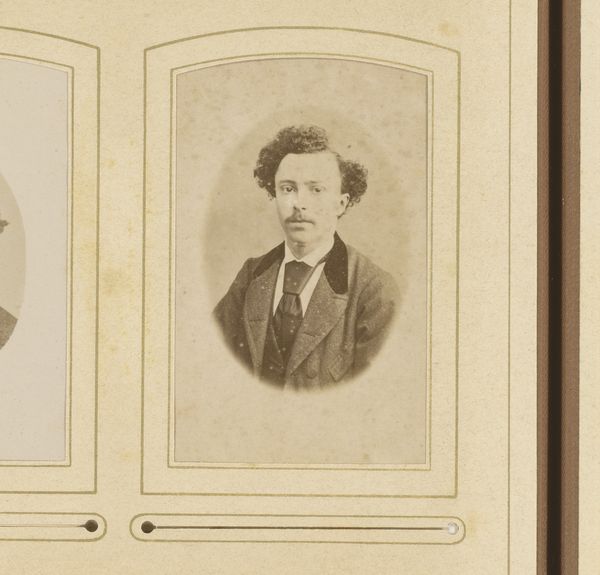

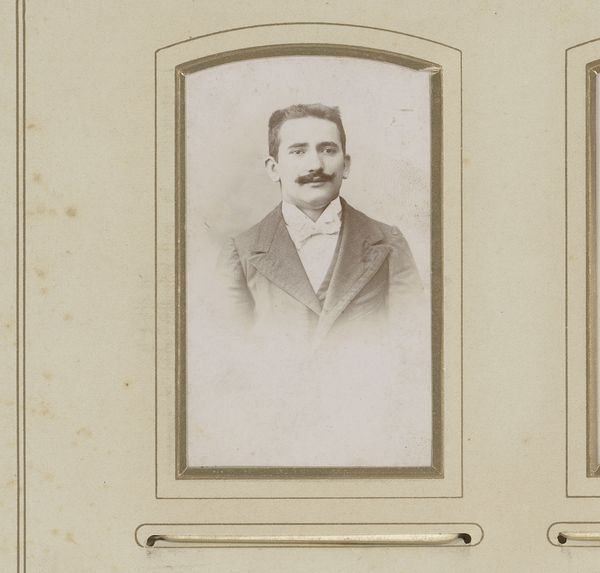

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

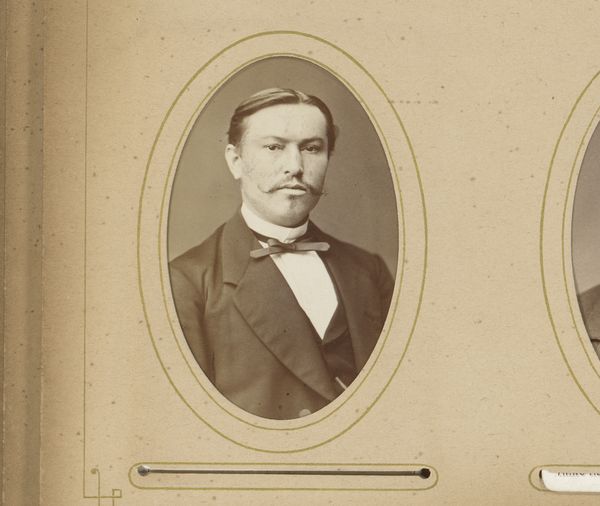

Curator: Standing before us is an intriguing photographic portrait, titled "Portret van een man met snor en sik," dating from around 1875 to 1899, attributed to Photographie Française of Amsterdam. Editor: My first impression is of understated formality, even austerity. The limited tonal range emphasizes the sitter's somewhat melancholic gaze and the deliberate structure of his clothing. Curator: Indeed. Focusing on its construction, we see the photographer utilizes a classic oval frame, softly blurring the edges to focus our attention on the sitter's face, particularly his carefully groomed moustache and goatee, which provide a strong visual anchor. Semiotically, facial hair of this style connoted a certain bourgeois respectability during the late 19th century. Editor: While you dissect the representational strategies, I find myself drawn to the materiality. Look at the paper stock; probably albumen print, judging by the warmth of the sepia tones, now fading with age. And the fact it’s part of an album page tells me this wasn’t conceived as high art, but functional ephemera produced for and consumed by a burgeoning middle class who newly had access to photography studios. What labour and economics went into producing so many cartes-de-visite in this era? Curator: That tension between the artistic portrait and industrial photography is exactly what characterizes realist art. However, I wonder if the careful arrangement of light, specifically the shadow on the right side of the sitter's face, isn't an appeal to painterly conventions. This choice elevates the photograph beyond mere reproduction. Editor: But those very conventions were themselves constructs determined by class, economic realities, and industrial capacities. I think we risk obscuring the social forces at work by prioritizing aesthetics. Who decided this person was worth photographing? What was the labour, who mixed and disposed of chemicals, what do we read in those material costs? Curator: A vital reminder that our aesthetic judgments are always grounded in material conditions, thank you. Editor: And in turn, that material conditions also shape the visual language and cultural meanings we then inherit, and reify, and repeat.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.