drawing, dry-media, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

dry-media

#

pencil drawing

#

underpainting

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

nude

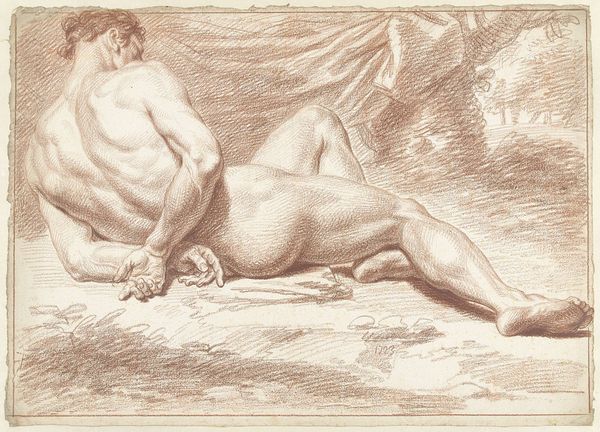

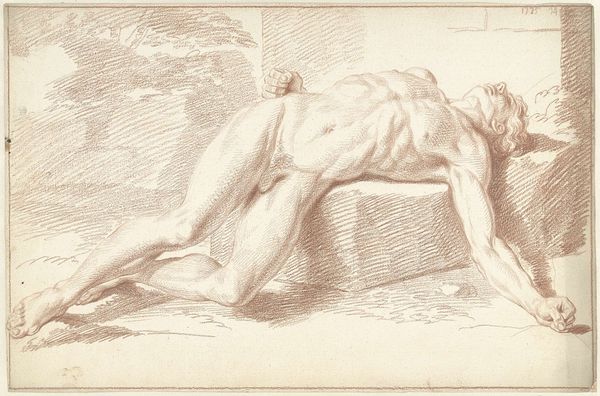

Dimensions: height 395 mm, width 564 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I’m struck by the stillness of this reclining nude. It’s executed in sanguine pencil—that warm, reddish-brown—which lends the piece a dreamlike quality. Editor: Indeed. What we're looking at is a drawing by Cornelis Joseph d'Heur, dating sometime between 1717 and 1762. It is currently titled “Liggend mannelijk naakt”–which translates to “Reclining Male Nude." Curator: The pose is so languid, almost as if he's lost in thought or perhaps sleeping, which contrasts sharply with the rather formal tradition of academic figure drawing. The relaxed pose speaks to an interiority often missing in more idealized representations of the male form. Editor: You see that quite acutely. D'Heur worked during a time when academies dictated artistic training, often emphasizing precise anatomy and classical poses. But look closely: see how the background remains a suggestion, an underpainting to highlight the foreground, not a narrative or an attempt to suggest the heroic. Curator: It really draws attention to the vulnerability of the figure. It feels less like an exercise in technical skill and more about the emotive effect on the viewer. Consider how he places his hand—it seems protective but also revealing. Perhaps an echo of ancient protective gestures like the *manus obscena,* but transformed into something less overtly symbolic. Editor: Or a subtle rejection of Baroque ideals, embracing instead a softer, more intimate naturalism that would become increasingly popular during the 18th century? How institutions slowly embrace evolving taste and politics... The art market during D'Heur's time played a crucial role too. Academic nudes, even those by lesser-known artists, found their niche within the evolving cultural attitudes toward anatomy. Curator: And also consider this as a kind of portrait, if we accept this is someone he knows, the act of sketching his relaxed, vulnerable form captures a fleeting emotional reality, and reveals aspects of social life—a private performance made public on the page. The line of sight to the subject requires a proximity charged with emotion. Editor: It's this tension, this negotiation between artistic tradition and something more deeply felt, that I find so compelling in d’Heur's work. Curator: Absolutely. It reminds us how potent images are as cultural artifacts, charged with meaning across eras, always being redefined through the changing lens of our interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.